Aruna Roy is unusual. Unusual in what she thinks, says, does; unusual in what she means to people and organizations, unusual in all that she has been. Her friends, colleagues, the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan of which she is the inspiration, know this to be so. All those who have worked by her side for the Right to Information Act and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act know this to be so.

Her new book — The RTI Story (Roli, 2018) — is also, therefore, unusual. It carries a telling subtitle: Power to the People, and an author byline which is vintage Aruna - "Aruna Roy with the MKSS Collective". It reflects her instinctive merging of herself in collectivity, in being with people, among their travails, for their thirsts. This is how she is.

A book being co-authored is taken to mean that it has more than one author, that it is by so and so et al. But here we have a book that is by the author so and so and another, that 'another' being not another so and so but a collectivity. Whence "Aruna Roy with the MKSS Collective".

This 'with'-ness is not about pride of numbers, or just of being part of a team of committed associates. It is about a reflexive identification with people's needs as personal as hunger and as 'public' as rights. And about faith in collective action to meet those needs. Ever so gently but firmly she shifts, always, the spotlights from herself to her colleagues and to her struggles. It is always 'we', 'our struggle', 'our movement'. No Aruna, no MKSS is how we would put it; no MKSS, no Aruna is how she would see it.

For too long now, personality cults and cultism have overwhelmed public initiatives. A charismatic leader gives voltage to a movement, powers and drives it. But the driver's seat has too many mirrors and before the 'driver' realizes it, narcissism has taken over, the movement has become indistinguishable from the leader, wholly 'led'. And sooner than one would have thought, the movement's leader becomes the movement's liability.

And so for any person to place a goal before the people, galvanize support, face opposition, repression, brutality, misinformation, interact with masses of people, media and agencies of the State, it would be intelligent to do so with a team. It would be intelligent and wise to have a group of thought-partners, action-partners. You can fast alone, write and speak alone; you cannot mobilize a rally alone.

Like-minded idealists pool their intelligence, turning an impulse into a movement. Like-minded crooks pool their cleverness, turning their motivation into crime.

At a discussion around her book in Chennai on April 16, Aruna Roy said in passing that there is a difference between intelligence and cleverness. And that brings me to the theme of this column: intelligence or, in Sanskrit, buddhi and cleverness, chaturyam.

Buddhi is an intellectual or mental faculty to understand, comprehend, reason, judge. It is to have acumen, discernment, perspicacity. It is to have insight, wit. At one level higher, it is about wisdom.

Chaturyam is a knack rather than a faculty, unless a knack can be taken to have become in the clever one's hand a faculty, talent, skill. It is about quick thinking, being smart, adroit. It is about being ingenious, artful, canny. At one level lower, it is about cunning, deviousness, foxiness, guile.

Buddhi is respected, chaturyam is acknowledged.

Buddhi is about the mind — manas — which is the confluence of the cognitive brain, the empathetic heart. It is the smeltery where ingots of intelligence become the lava of insight, analysis turns into understanding and reason, 'cold' reason, thaws into that state of consciousness which Sanskrit describes easily as chetas.

In the cosmos of buddhi, there is space for introspection and, therefore, for self-doubt. Buddhi is fallible and it follows that buddhi is capable of remorse, atonement, correction. In the stratosphere of chaturyam, there is no time for reflection, no room for self-doubt. Self-advancement being its goal, its attitude betrays no insecurity. Chaturyam is no less fallible than buddhi but when its manoeuvre fails it does not give up on manoeuvring, only replaces manoeuvre by manoeuvre.

Buddhi is active, chaturyam restless. Buddhi looks ahead, chaturyam sideways. Buddhi knows repose, chaturyam knows to pose. Buddhi knows a hundred different laughs and can dissolve in a hundred tears. Chaturyam knows only one laugh, the laugh that laughs at a rival's setback. It has a hundred different smiles, though, which serve a hundred different purposes — the quarter-smile, the half-smile, the winking smile, the smile that asks, "How about another?"

Buddhi is wise, chaturyam is smart. Is there an equivalent in Sanskrit for 'smart'? I do not know of one. But there is in Persian a perfect equivalent for it, chalak. And chalak has an abbreviation that performs the same duty more street-wisely — chalu.

The difference between buddhi and chaturyam is vital to the protection of India's constitutional integrity. Our Constitution makers had buddhi, they were noble. Our Constitution manipulators have chaturyam, they are smart.

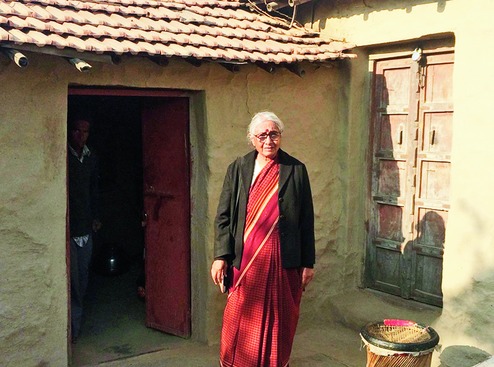

The RTI story and the career-path of the MKSS are about how buddhi, ethical, brave, strong, has prevailed over chaturyam, sly, smart. Aruna and her pioneering colleagues — Nikhil Dey, Shankar Singh and his wife, Anshi — each endowed with a buddhi that was her or his very own, shared a perspective and determination to challenge the exploitation of workers and peasants as a team. They saw that India, rural India in particular, was hostage to two patriarchies — influence (pahunch) and money (paisa). If one did not have either of these, one sank. Mobilizing people for a retrieval of their rights against pahunch and paisa, Aruna, who had quit the Indian Administrative Service, Nikhil Dey, who had exited from college in America, Shankar and Anshi with their deep insight and lived experience of life in Rajasthan, started the MKSS collective. They faced cynical disdain, ridicule and super-smart resistance from a feudal, patriarchal order mired in corruption and bureaucratic lethargy.

And as they moved into their hamlet of Devdungri (Rajsamand, Rajasthan), teaming up with the gutsy Naurtidevi of the Harmara panchayat in Ajmer district, they saw that the ending of immiseration would be a lifelong struggle, becoming tougher with failures and even more tough with successes, for then new expectations arise, new peaks swim into view. These new peaks included an awareness of the need for accountability and transparency, not through appeals but through legal mechanisms — RTI. And also of the need for guaranteed employment, not through anyone's charity but entitlements — NREGA.

The then United Progressive Alliance-I government, not without agonizing delays and prevarication, saw the merit of the MKSS's strivings. Its national advisory council invited Aruna to join, and M.S. Swaminathan, Madhav Gadgil, Jean Drèze, Mihir Shah, N.C. Saxena, Harsh Mander, Jayaprakash Narayan and others of the same persuasion, transforming a movement into a legislated reality. Wajahat Habibullah as the first chief information commissioner was pioneering. And judges like Prabha Sridevan and Chandru in the Madras High Court made the RTI come alive through judicial orders. All that was buddhi's victory over chaturyam.

But chaturyam is ever at work. It must not be allowed to prevail over buddhi's ethical sway.