Since the second wave of immigration from the 1960s to the present, Indian Americans have become a force to reckon with in terms of their numbers and their financial and political clout. There are between 2.5 to 3.3 million Indian Americans in the United States of America today: one in 10 Americans is from India. Since the nineteenth century, Indians have been living in America, especially in California. They worked on farms and helped build the railroads. But it is only now that influential Indian Americans are in a political battle to define themselves as distinct from others of the Indian subcontinent. They are doing so by showcasing their political, professional and cultural contributions and by intervening in the arena of education in a bid to influence how India is perceived in America.

This desire for self-representation was most clearly visible in the Smithsonian's exhibition, Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation (February 2014-August 2015), at the National Museum of Natural History. The exhibition is currently travelling across the US, and is also accessible online. It was the brainchild of a group of Indian Americans who approached the Smithsonian and bankrolled the expensive project. Their objective was for non-Indian Americans to learn about them, and for Indian Americans to connect with and share their past.

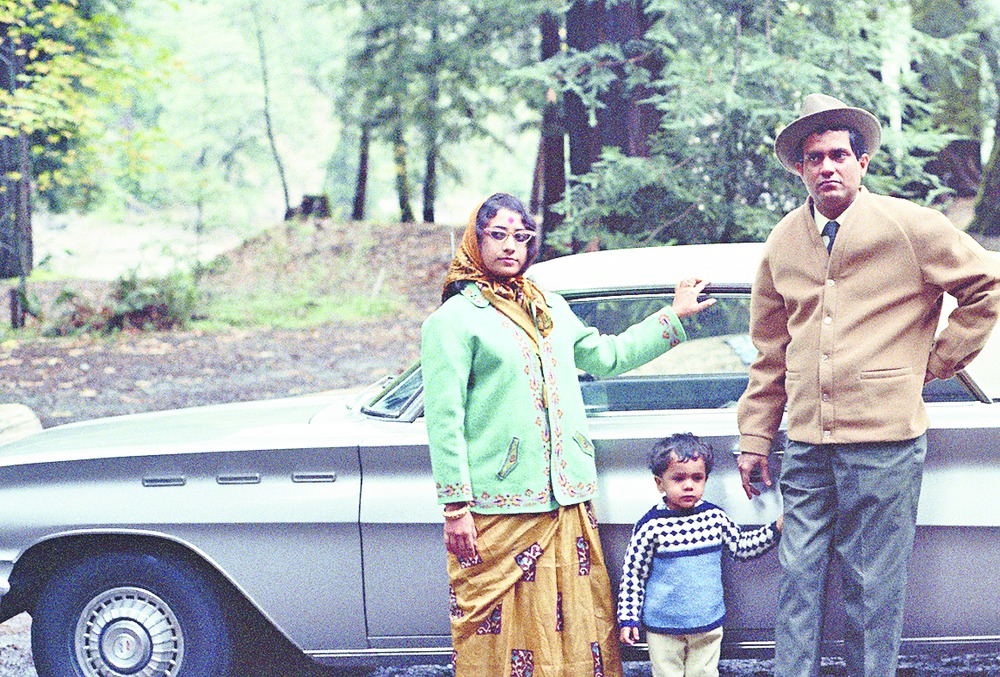

The 5,000-square-foot exhibition space - it was attractively presented in brilliant colours and with interactive exhibits - was curated to explore the heritage and daily experience of Indian Americans and the diverse contributions they have made to the US. There is a small section on the early Indian immigrants to California and fleeting references to the racism they faced and overcame. There are interesting exhibits like Suitcase Stories that display the material objects the immigrants brought with them in addition to their hopes and dreams. There are tales of family journeys and photos of sari-clad women in cardigans standing beside their large American cars. Images of Indian weddings performed in suburban homes, bhangra dance performances and yoga are all on display. One can hear clips of North and South Indian music, explore the contents of an Indian-American kitchen, smell a variety of spices and look at Indian cookbooks.

The project's primary intent is to celebrate Indian Americans - a feel-good project. Thus, it glosses over the blatant racism that Indian Americans have faced, especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is the contributions of Indians that dominate the exhibition; certainly, this has been the case with the digital version that I have reviewed. Indian-American achievers run the gamut from the entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley to Brandon Chillar, a team member of the Green Bay Packers Super Bowl line-up, who is the first Indian to play and win a National Football League championship, and Naeem Khan, who designs glittering gowns for the likes of Michelle Obama, Beyoncé, and Penélope Cruz.

The exhibit displays such startling and flattering statistics as 73 per cent of National Spelling Bee winners since 1997 have been Indian Americans, a contest that Indian Americans take very seriously. Thirty per cent of all H-1B visas are granted to Indians, a trend that started in the 1960s when America, faced with the growing threat of a nuclear Soviet Union, allowed Indian scientists and engineers to join Washington's efforts to keep the US competitive in the global arms race. Indian scientists have developed Hotmail, the Pentium chip, fibre optics and noise-cancelling headphones, all of which are featured in the exhibit.

Whereas the exhibition has garnered a great deal of positive responses, it has been criticized by some for presenting a very celebratory, North Indian and Hindu-centric perspective of Indians in America. Some are angered that it seems to exclude Muslims from among those who call India home. "The unique relationship that expatriate Indians have forged with Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Sri Lankans, and their descendants via the Caribbean - collectively called desis, or the more clinical 'South Asian' - is hardly explored," says S. Mitra Kalita in Quartz magazine. Some of the pertinent questions raised include whether hyphenated identities are meaningful in a globalized world, and if claiming an individual's achievement as an entire community's is to imply that some communities can make it and others just never will. Younger desis don't necessarily feel that the term, Indian American, fits them, and some argue that "South Asian" leaves out America.

A more intense identity struggle is taking place around California's school curriculum, exposing the same fault lines in the Indian American community. A committee has been tasked to update and revise curriculum for grades six and seven to make it more inclusive of the state's diverse population. Religious groups are weighing in to represent their traditions and heritage in a manner that will not hurt the sentiments of students following particular religious traditions. The Hindu American Foundation sees itself as the guardian of Hinduism in the US, and is joined by some students of Indian descent who are adamant about making revisions to what they claim are grave errors in the textbooks. For example, they want to use the term, India, for the region and do not like the ways in which caste has been represented as a part of Hinduism rather than being presented as a regional phenomenon.

Meanwhile, a group of eminent South Asian faculty members across American universities is concerned that this intervention by the HAF is an attempt to sanitize history. They oppose the HAF's desire to include modern-day India, Pakistan and Nepal as 'India'. The use of "India" in place of "South Asia", they argue, distorts representations of the Indus Valley civilization and indicates the latter's assumed connection to Hinduism.

Other South Asian scholars believe that the use of the term, India, by Hindu nationalist groups refers to a geographical area that today includes several countries other than India. They view this as an attempt to advance a militantly expansionist idea of India. Furthermore, there is an outcry against suppression of the religious origins of the caste system, erasure of the word 'Dalit', stripping Sikh migrants of their identity, expunging Guru Nanak's denouncement of caste, inserting statements that deny the syncretic nature of Islam, all of which is deemed to be politically motivated and pernicious. The preoccupations and passions of the non-resident Indians are an important facet of the Indian American mosaic. They are far more immersed in the politics of the subcontinent and further complicate and intensify the contestations around identity that are being forged. They are also fuelling this debate. The curriculum controversy has assumed an ugly tone, including malicious campaigns of harassment against committee members and consultants, thereby muddying the waters further.

Both the Beyond Bollywood exhibition and the California textbook controversy are politically loaded. They are playing a role in shaping the next chapter of the Indian American experience. This stage is far more complex than when Indian Americans in the nineteenth and late-twentieth century were struggling to make a life for themselves in the US. Today, many Indian Americans have made it in politics across the political spectrum and are leaders in business, technology and the arts. Young desis are not just better integrated in the fabric of America, but are part of a larger South Asian culture. The contestation of who and how Indian America will be represented is in full play.