That was a sumptuous banquet alright. If the viewer burped, it was from satisfaction, not indigestion. Because Akar Prakar's recent show, Synchrome-Masters, did, indeed, line up the masters. Well, yes, caution is advised when approaching works of those no longer around. And a majority shown here aren't. Without specialized examination, it's difficult to tell genuine from spurious with the naked eye, especially since skill and technique are purchasable. Galleries thus need to be vigilant in scrutinizing their provenance with care. But the viewer, without the burden of the authenticator, can guiltlessly savour the period ambience evoked.

Forty-one artists from about three generations — those born in the late 19th century; those in the early years of the 20th; and those in the 1930s — were represented, each contributing to the making of the modern age in Indian art. The gallery was judicious in giving space for just one work to each artist in most cases which balanced the weight of big names with economy in presentation. Besides, the Tagores are conspicuously omitted, with possible plans for a later display.

Not surprisingly, the accent is on drawing and sketching, on the irrepressible sentience of lines, to be precise. And that referred, quite compellingly, to what was the veritable anchor in traditional Indian art, whether Ajanta and the Miniatures or the Jain manuscripts and folk/tribal expressions. In fact, drawings and sketches come from a number of artists: K.C.S. Paniker, A.A. Almelkar, Manjit Bawa, F.N. Souza, Akbar Padamsee, A. Ramachandran. The wry figuration of K.G, Subramanyan’s watercolour sketch must be counted in this company as well. While a wall is devoted to Ganesh Pyne’s Jottings, a comically distorted figure — like in illustrations — is by Bikash Bhattacharjee.

But to plot the narrative of modern Indian art around the masters you must begin with the earliest presented here: Dhurandhar. His pencil drawing of a pertly confident working class woman dated 1938 is merely an exercise and speaks of the British academic naturalism of the art schools in the late 19th century. But its meticulous fidelity is rejected by Nandalal Bose, whose flourish of lines is seen on a postcard he wrote. His practice of showering these little sketches on his correspondents tells you how alien the Western concept of the exclusive signature was to this generation.

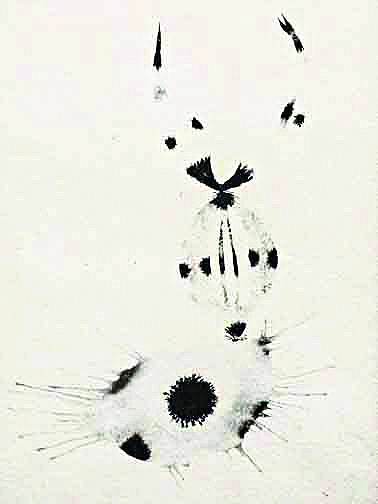

And that, of course, includes Jamini Roy, who followed the patua tradition in replicating —with assistance, it’s rumoured — his own images; and the later Chittaprasad, who sometimes refused to sign his work due to ideological reasons. The four spare engravings on slate by Roy are undated but seem to suggest a phase when he was perfecting his mature idiom. And the 1960 portrait of a rugged, weathered face with sternly penetrating eyes by the latter recalls the manifesto-driven art of the famine years. Nandalal Bose’s students find themselves near their Mashtermoshai. The ink- and- brush trees of Benode Behari Mukherjee are tiny, yet replete with a gentle, East Asian lyricism, Santiniketan-style; and what’s noticeable about the calligraphic watercolour lines of Ramkinkar Baij, that sometimes blot into bushy capillaries, is their breezy energy.

To come to Paritosh Sen and M.F. Husain, Sailoz Mukherjea and S.H. Raza is to look at a generation that had outgrown the earlier obligation of Indianness, and chose to raid both Western and Indian sources, including folk/tribal visual dialects, in their search for form. Raza, of course, discovered his own language of Indian geometry, while Mukherjea’s brooding romanticism suffuses a fine landscape on view (picture, top). Speaking of landscapes brings you to the agitated strokes of Gopal Ghose’s watercolour and the short, bristly jabs in Paramjit Singh’s mixed media work, so unlike the flowing lines that counterpoint the taut rigidity of a horse in Nikhil Biswas’s On Defeat.

But abstraction, meanwhile, was scripting a parallel tradition, partly authored by V.S. Gaitonde, represented here by a signed print. Ram Kumar's black and grey bands - pale, dark, overlapping, staccato - bring to mind the reflective reticence of his junior contemporary, Ganesh Haloi, though the latter's watercolour here is a blend of foggy greens and mustard. But the best of the abstractions comes from Laxman Shreshtha with its smudges of black and sooty vapours; and J. Swaminathan, whose seminal role in both articulating this alternative vision and discovering for urban artists the tribal tradition can hardly be overstated.

To end with the sculptures. There were two elders: Prodosh Das Gupta, seeking to wrest muted form from mass as in Lying Amazon; and Sankho Chaudhuri, abstracting its essence intuitively. What disturbs the viewer, however, is the environmental warning in Meera Mukherjee's bronze.