|

|

| Woman’s affair |

Innumerable novels, short stories and poems have been written on the unbelievable violence that took place with the Partition of the country in 1947. Upwards of a million innocent men, women and children; Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs were massacred in cold blood. To describe these killings as bestial would be doing injustice to beasts: animals never behave in as brutal a manner as humans.

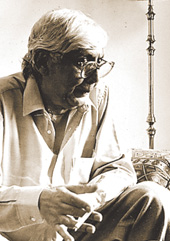

Of the spate of literature produced on the subject, without doubt, the most powerful were the writings of Saadat Hasan Manto in Urdu. His one short story, “Toba Tek Singh”, encapsules the beginnings of the tragedy, the lunatic heights of depravity it reached (Manto was, for a while, a patient in Lahore mental asylum) and the utter futility of it all. There were times when a man’s life depended on whether or not the foreskin of his penis was circumcized: if it was, Hindus and Sikhs killed him along with his women and children. If it was not, the Muslims killed him along with members of his family. It was as simple as that.

Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) was born in Amritsar, educated in Aligarh, worked for All India Radio in Delhi and made films in Bombay. He was hounded out of Bombay and rejoined his family in Lahore, where he died and is buried. He was often in trouble with the police for writing obscene stories but had a large number of admirers who stood by him in times of trouble.

Besides “Toba Tek Singh”, Manto penned short vignettes loaded with sardonic wit and irony to highlight the total lack of sense behind the religious divide. They were published separately at the time of Partition under the title, Siyah Hashiye. Rakhshanda Jalil, freelance writer and translator of many Urdu works into English (she taught English in the universities of Delhi and Aligarh), has translated 32 of Manto’s cameos into English: Black Borders. It is a slender booklet worth every one of its 50 pages. I quote two items from it:

“Leading by example”: “The entire neighbourhood perished in the fire — only one shop remained intact. On its shop-front hung a board that announced: ‘All types of Building Material sold here.’”

There is also a gem entitled, “Shoe”: “The tide turned and the crowd chose to vent its anger on the statue of Gangaram. They rained sticks and rods, threw stones and bricks. Someone climbed up with a pail of tar and blackened its face. Another collected an armload of old shoes, strung them into a garland and was about to put it around the statue’s neck, when the police showed up and began firing. The man who was about to put the garland of shoes around the statue’s neck was injured in the police firing. He was sent to the Sir Gangaram hospital for treatment.”

Songs for lovers

In Indian weddings, there is more festivity in the bride’s home than in the bridegroom’s. In Punjab, it starts with dying the palms of the bride and her friends with henna (mehndi); an evening is devoted to sangeet (song) by girls to the beat of the dholak (drum) and the tick-tock produced by a coin struck on an empty gharaa (pitcher). The actual ceremony of going round the sacred fire or the Granth Sahib (laavaan pherey) is too solemn a ritual to be sung about. The last rite is a tearful affair of the bride taking leave of her family and getting into a palanquin (doli) to be carried off to her new home. Of all these events, the most popular is, and was, the sangeet. Though a ladies’ affair, men are allowed to sit around.

The songs are pretty meaningless. In my Lahore days, the chief attraction at ladies’ sangeet was Shan, the wife of the lawyer Gurdev Singh who later became a judge of the high court. She was pretty, petite, goree-chitti (fair as fair can be) and very animated. She spoke only Punjabi in the Pothohari (Rawalpindi Campbellpur) dialect and I assumed she knew no English. I was wrong. A year ago, she came to see me with her America-based daughter, Tito, and showed me some translations she had made of Punjabi folk songs into English. I could not fault her on any word. She has put together 30 of the most popular songs in their original Gurmukhi, along with translations in English in Songs Remembered: Folk songs of Punjab, which also has illustrations by her daughter.

As I said before, there is more emotion than poetry in these songs. Shan’s collections are entirely feminine creations, addressed to lovers. The first one is to a village Romeo, named Paras Ram. She invites him over to her garden where mangoes and bananas grow and the koel sings on the bough. He is asked to hurry up because today her hands would be smeared with henna, the next day would be ladies’ sangeet and the day after, she would be carted off in a doli to her husband’s home.

An all-time favourite, Soohey vey cheray valia main kalnee aam:

My love in a red turban, listen to what I say:

I tell you open up your umbrella

Will sit under its shade

The keekar tree is in flower

Friends gathered under a bower

Most songs used archaic words like mahia or dhola for lover.

Shan Gurdev Singh’s compilation is strictly for women. There is an equally rich corpus of male folk songs, mostly bawdy in character. The most popular is about a randy old man (baba) which began with a meaningless jingle:

Toomba Vajdai na

Taar Binaa

Rahndi na

Yaar binaa

(Without a string no lute can play/ Without her lover she will not live a day.)

The baba of this once-popular folk song was as mean as he was lecherous. After spending a whole night with a whore, he gave her a counterfeit four anna piece and not a paise more. The baba was full of bright ideas (bada bajogi). He made love to a she-camel using a ladder. I’ve not heard of the exploits of baba in 50 years.

We have all been there

There were eight women in the office and one man, the boss. They soon learnt that his favourite topic was his many and varied illnesses. Whenever one of the women mentioned an ill-friend or a relative in hospital, he wanted to know in which ward he was. Invariably it turned out that he had once been in the same ward.

One of the senior staff-members, dying to outsmart him, said to him one day, “By the way, sir, my niece is in the hospital.” His face lit up. “Really? Which ward is she in?”

Enjoying her moment of triumph, she replied, “Maternity — you’ve never had reason to be in that ward.”

“Of course I have,” he answered. “Even men are born in ‘maternity’ you know.”

(Contributed by Reeten Ganguly, Tezpur)