|

|

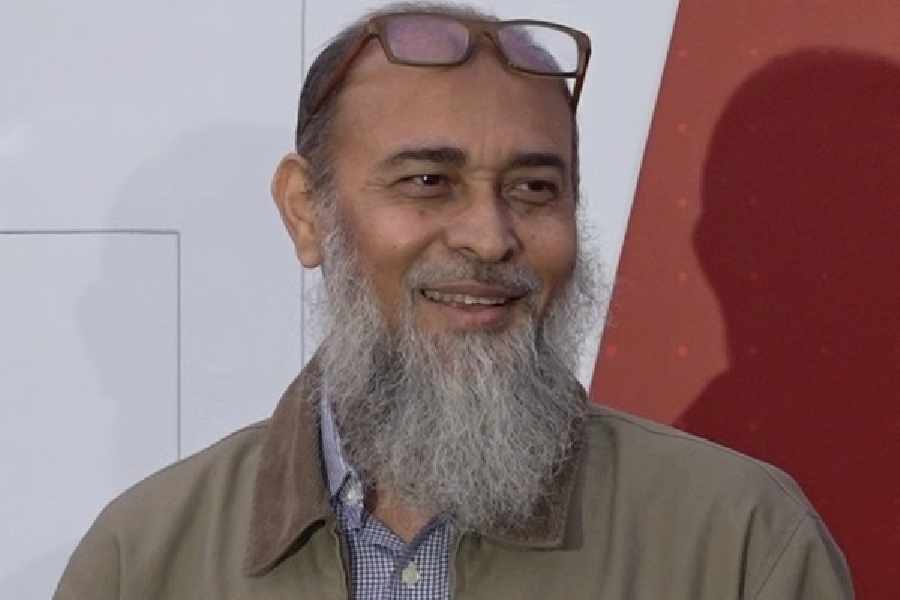

| Scene from Babarer Prarthana |

Some of the younger groups in Bengali theatre are fighting international and sectarian violence in unusual ways, keeping the flag of the movement’s political activism flying. In their latest efforts, Kalyani Natyacharcha Kendra and Chokh have staged original plays, both of which turn to verse literature for their sources, going back to historical and legendary materials respectively.

Babarer Prarthana by the Natyacharcha Kendra from Kalyani, now no longer an alternative but an established hub of theatrical activities in West Bengal, has an interesting genesis. The playwright, Bratya Basu, dramatized it from the title poem of Sankha Ghosh’s volume that won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1977. Converting a 24-line lyric into a full-length script is to put at risk the values of concision and metaphor that give poetry its distinctive beauty. To Basu’s credit, he holds his reins on a tight leash, except for one sequence (more on that later).

Ghosh’s original drew upon the tradition that Babar prayed to Allah to cure his mortally-sick son, Humayun; to take his life and give back Humayun’s. His wish came true: his son recovered miraculously but he died soon after, prematurely. Autobiographically, Ghosh had his own young daughter’s battle with death on his mind, yet he also sublimated the personal trauma into a supplication for the lives of all the youth of the disturbed Seventies, dying while their elders lived. Basu, resisting the urge to romanticize the Seventies, contemporizes this into a plea for today’s younger generation across the world, sucked into political violence and uncalled-for death.

The director, Kishore Sengupta, expresses all three levels of appeal in an impressionistic dramaturgy, presenting the Mughal story in period regalia, the minimal scenes of the professor, his child and her doctor in a modern hospital, and the theme of wasted youth in episodes on a terrorist cell startlingly similar to the Kendra’s own previous production of the conspiring revolutionaries in Camus’ The Just, titled Hariye Jay Manush. The dramatis personae of 24 characters does not permit prime time to anyone in particular, but the scene lampooning Bush, Blair and Bin Laden interviewed on a TV talk show unnecessarily cheapens the tone, however much one may detest the Right or fundamentalism of any colour.

Chokh’s enterprise, Atahkim Mahayuddha, goes to the other extreme on the scale of difficulty by condensing some of the early books of the Mahabharata into two hours on stage. If anything, this is a more difficult job than expanding a poem, for how does one decide what to leave out? All performance editions of our grand epic invariably succumb to this weakness, the greatness of the régisseur not reducing the criticism, as Peter Brook discovered after his versions.

The dramatist-director, Abhijit Kar Gupta, lessens the load considerably from Vyasa’s full eighteen parvas, by examining only the reasons for the Kurukshetra war, ending as it begins, so as to extrapolate them on the causes of conflict in our times. But how comprehensive can even this brief be? If we omit the Adi, Vana and Virata parvas as extraneous to this purpose, two entire parvas remain, the Sabha and Udyoga, just these two totalling, for instance, 1,300 pages in P. Lal’s complete verse translation. Despite editing out digressions, how much of this sprawl can one production retain?

Kar Gupta also seems to rationalize the “glorious war” as justifiably good versus evil — the traditional and rather simplistic view. If he reads the Udyoga parva closely, he will find a much more complex scenario on the ground. The Pandavas fight for their rightful inheritance no doubt, but the Kauravas have the letter of the law on their side (Pandu did not father his five sons) and cannot afford to set a legal precedent. Furthermore, every major debater in the negotiations mouths intriguing sophistries and highly sophisticated arguments, many of which Kar Gupta lets slip.

He interprets the Pandavas as oppressed by “a totalitarian state which attempts to obliterate (their) very identity”. In doing so, he does provide a fine sense of the futility of pacifist moderation and the inexorability of the war. Among the cast of around twenty characters, we notice the unconventional representations of Arjun and Bhim, breaking out of their stereotypical physical attributes, whereas the other important characters in this dramatization (Krishna, Dhritarashtra, Gandhari, Vidur, Shakuni, Yudhishtir, Duryodhan, Draupadi) stay more or less true to type.