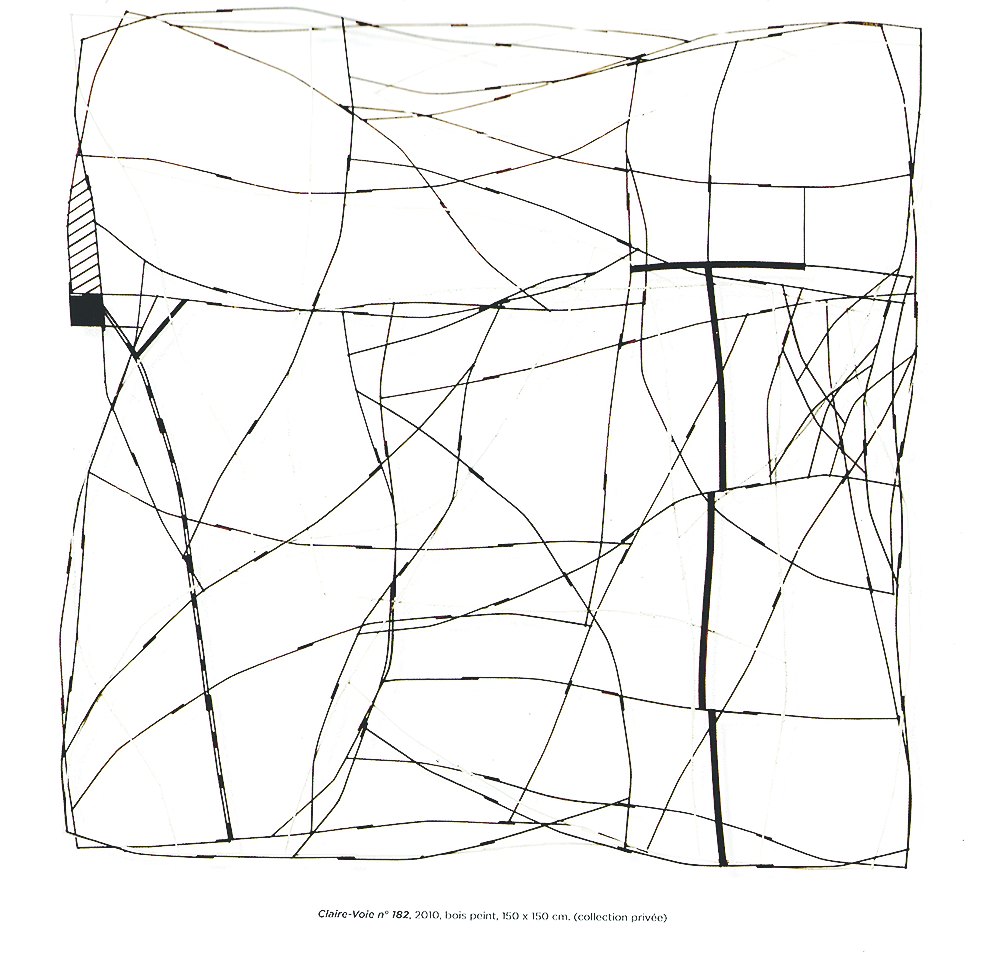

Paul Klee is the artist whom Francis Limérat admires, and Klee once wrote: "Drawing is taking a line for a walk." This statement offers a clue to understanding this Paris-based artist's recent work, now being exhibited at Akar Prakar in collaboration with the galerie baudoin lebon in Paris. Limérat has nothing in common with Klee's playfulness, colour and infinite variety, but lines are certainly the essence of his work, and that is where their thoughts converge. Taking off from reality, Limérat makes drawings, and the most fragile wooden frameworks that owe much of their existence to cartography, but only insofar as the lines are concerned. Limérat does reference landscapes and the maps of cities, but his works exist independently of either, as abstract art usually does.

Because of his affinity with Klee, Limérat's work comes close to modernist practice, although he cannot be confined to that definition alone. Shadows enhance the aesthetic pleasure of viewing Limérat's jagged work often structured with bits and pieces of wood whittled down to sticks. In daytime, when the direction of light keeps shifting, so do the shadows. So he calls these "living pieces" as the shadows create a kinetic illusion. These can also be read as extensions of his drawings, for they are fine webs of lines fashioned out of wood.

However removed Limérat's work may be from concrete reality, the starting point is always a stark landscape or cityscape, or even a roadmap where the lines are simple - straight or curved - analogous to geometrical drawings, or in a way even blueprints. Limérat, who has taught art for more than three decades in France, and was himself trained as a classical artist, makes a preliminary drawing of the topography, and later draws it again on paper using his notebook as his aide-mémoire.

The two drawings are superimposed and the gaps between the two lines are painted sepia and then buffed with an emery board - frottage was a technique Klee also favoured. Of course, the artist picked and chose the lines he wishes to retain, and which ones to erase.

His drawings with their tracery of lines are uncannily similar to the works of Ganesh Haloi in their concept. The local topography with its rows of rectangular paddy fields and structures with a geometric design act as stimuli for Haloi's imagination, and he creates numberless variations on the same theme. Limérat's drawings, however, are more austere than the paintings of Haloi, which are coloured in various though subdued hues. This is the point where Limérat deviates from Haloi, for the former uses only black or sepia.

But as Limérat admitted in an earlier interview, the sensibility of both artists is the same. Both take in the particulars of a landscape, and gradually start the process of paring them down to the barest minimum. This Limérat does quite literally when he puts together those bits and pieces of wood to create the tangle of lines, one of which is a little broader than the rest like an arterial road.

The process is the same as in his drawings. He superimposes the wooden structures (he used matchsticks softened with water for his current show) he makes. Once again he used reality as his starting point, and his memory of seeing it to create these. Then like a gardener using shears, he spontaneously cut out the portions he felt were redundant, and gave the jali-like structure some breathing space. It thus becomes more focused. Limérat was born in Algeria and is not unfamiliar with openwork, and it is this effect that he tries to recreate in a small section of these works made of wood. Occasionally a feeling of sameness does creep in.

These are all two-dimensional works - horizontal and elevation coexist. Although these are hung on walls during exhibitions, they can be displayed on the floor too. This is an idea Limérat borrowed from the 17th century military engineer, Vauban, whose forte was designing fortifications and breaking through them. Vauban's citadels were typically star-shaped, and Calcutta's Fort William was modelled on his defensive concepts.

To quote Paul Klee once again: "In the final analysis, a drawing simply is no longer a drawing, no matter how self-sufficient its execution may be. It is a symbol, and the more profoundly the imaginary lines of projection meet higher dimensions, the better." Limérat's work can be read as a dialogue between realities - physical and imaginary - between motility and rootedness, and the play between the flimsy wooden structures and their shifting shadows.