|

|

Arghya, set up in 1996 with the avowed aim of doing politically-conscious theatre like most Bengali groups, has travelled a long way. Over the last four years, it has undergone what current jargon likes to call a “paradigm shift”, from the contemporary to the classic and classical in terms of content, from the urban to the rural and traditional in terms of style. This does not mean that it has relinquished the political — for instance, its recent productions include Tagore’s Rakta-karabi. The move to study folk forms itself reflects an ideological desire to align with the common populace — but it does mean that Arghya has come of age, able to cope fluently with both the city and the village, encompassing a range and depth most troupes cannot boast of.

I must qualify that Arghya’s director, Manish Mitra, always showed interest in folk theatre, going back to Dakshin Rayer Pala (1999). But the earlier, more superficial, knowledge has matured as the consequence of determined journeys by the group to the homes of various gurus across India, from Teejan Bai to K. N. Panikkar, living with them, learning and imbibing their skills. This training has had its best result in Bharat-katha, a retelling of the Abhimanyu episode from the Mahabharat. Everybody knows the story, but Mitra worked on the basis that many traditional forms relate to versions of it. So he brings together on one platform the techniques of Chhau, Pandavani and Jhumur to re-present the tale, punning on its pan-Indian reach in the title (which, otherwise, would be a misnomer, for it only covers Abhimanyu, after all).

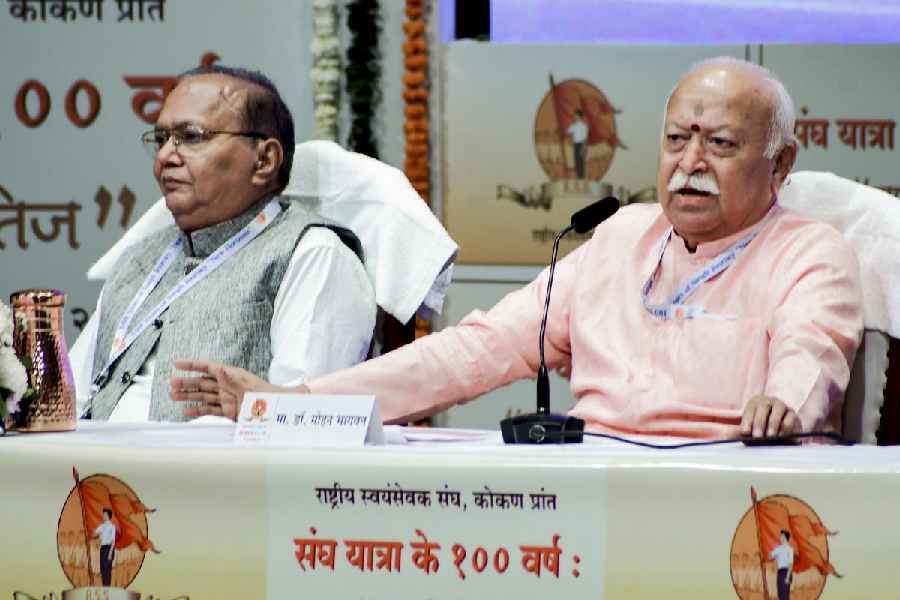

Mitra achieves a beautiful integration of idioms and languages here — the physical energy of four Puruliya Chhau- masked dancers, the one-woman narrative strength of Pandavani, the musical storytelling of Jhumur, the classical and Panchali vocals — but it must have taken some doing to make the blend seem so effortless. The powerful singing of Sima Ghosh (in Chhattisgarhi) and Anirban Ghosh (both in picture) contributes greatly to the impact; as does Jhumur singer, Anirban, who displays remarkable improvement and rigour of voice. I expected Mitra to conclude with the climactic Chhau pièce de résistance of Abhimanyu trapped inside the chakravyuha, but he says he requires seven dancers for that effect. I think, in the syncretic spirit of the project, all seven need not be Chhau performers.

In its latest production, Arghya takes up Kalidasa’s romantic lyric, Meghadutam, in the original Sanskrit, dramatized by K. N. Panikkar into Kerala’s Kuttu form. This puts the solo actor to severe test, which Ranit Modak (as the lovelorn Yaksha) stands up to, laudably internalizing the Sanskrit lines, just as Sima Ghosh did her Chhattisgarhi. But a Kuttu artist often deflects attention by digressing into comic topical anecdotes in Malayalam; without such corresponding material, Mitra sacrifices the entertainment factor. He provides a live Bengali paraphrase that lengthens and does not really aid the performance; perhaps he could resort to Bengali supertitles instead. That kind of technology is preferable to the amplification of the entire ensemble excellently playing Panikkar’s score which causes many remote-mike and balancing glitches and should not be needed by theatre practitioners in an auditorium anyway.

The folk/traditional trappings vanish in Rakta-karabi, but it is a classic, so Mitra’s rediscovery of the Indian heritage continues, more so since Arghya attempted the play back in 1996. In the revival, he edits the text quite a bit, understandably, but interpolates some passages from Tagore’s poetry and songs (and a narrator’s part) that ultimately do not seem essential, for he remains faithful to the source otherwise. Man’s depredation of the planet is his focus. For this to be interpreted, Sima Ghosh’s portrayal of Nandini as an innocent nature’s child looks appropriate. The more striking presence, though, is of Pallab Kirtania as Bishu, particularly for his robust singing. Among the supporting roles, Premangsu Dasgupta and Moonmoon Chatterjee merit mention, as an authoritarian but taciturn Sardar and a simple, no-nonsense Chandra respectively. For the set, Shuvaprasanna erects a huge monolithic profile of a head at upstage right, but it does not have much theatrical functionality. Mitra himself takes some images too literally, like the frog in the Raja’s hand, which resembles a stuffed toy. And, like virtually all actors of Tagore’s Raja, his, too, appears less than imposing when he finally emerges.