|

|

| Still without a peer |

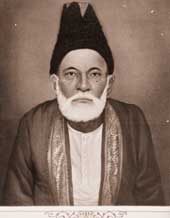

If you want to know what the greatest figure in Urdu literature, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869), looked like and how he lived in the Delhi of his times, you will not find it in his poetry — which is often difficult to comprehend — but in the letters he wrote to his friends and admirers. He was an inveterate letter-writer, four to five a day which he put in the post himself. Most of his correspondents were aspiring poets who sent him their compositions to correct: he did so with great care. In his replies, he invariably put in a couplet or two of his own and gave a detailed account of how he was faring.

K.C. Kanda, who has several books on Urdu poetry to his credit, has, in his latest publication, Mirza Ghalib: Selected Lyrics and Letters, 68 letters by the poet covering a period extending from a few years before the outbreak of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 to a couple of years before his death in 1869. A large number of these letters are addressed to his Hindu disciple and friend, Hargopal Tufta. Others to his patrons, including the Nawabs of Rampur and Loharo.

Asadullah Khan was a handsome man, tall and light-skinned, with an imperious martial bearing. His forefathers, who were Seljuk Turks, were professional soldiers. Asad was a man of peace and even as a boy studying Arabic, Persian and Urdu, he was convinced that he was not going to be a soldier but a poet. He took on the pseudonym Ghalib. He was married off in his teens. His wife bore him seven sons and daughters, all of whom died in their infancy. He moved to Delhi to gain access to the Mughal king Bahadur Shah Zafar, a poet of substance, and the nobility who patronized poets. His wife proved to be a poor companion. For companionship and pleasure Ghalib sought the company of dancing girls and prostitutes. He never earned enough to maintain his household in comfort and was always in debt.

Ghalib had no sympathy for the mutineers and stopped calling on Bahadur Shah Zafar, who had become a puppet in their hands. During the months the fighting lasted, he did not go out of his house. Evidently, families of Muslim hakims who too lived in Ballimaran, also did not support the mutineers. Consequently, when the British and their Indian allies re-occupied Delhi, they drove Muslims, who they suspected to have supported the mutineers, out of the city but allowed Ballimaran Muslims to stay on. Raja Mohinder Singh of Patiala put his troops at both ends of the bazaar to ensure their safety.

Ghalib mentions his daily routine in many letters. He was not an early riser because his nights were disturbed by malfunctioning of his bladder; he had to get up to urinate every hour. He had a frugal breakfast of peeled almonds and syrups, mutton broth at midday; four kebaabs and an ounce of wine mixed with rose water made up his dinner. During the mango season, he consumed upto twelve mangoes at one sitting every afternoon. His bowels were often out of order and boils erupted all over his body. He was full of remorse: “I am old, idiotic, sinful, sensual, profligate... a man lost to shame.” He describes himself sattra-bahattra. Before he was 70, he started losing his memory, vision and hearing.

Ghalib did not take religious injunctions too seriously. He had his own version of roza (fasting) during Ramadan. He writes: “I observe fasts, but keep my fasts well-humoured with occasional sips of water, and a few puffs of huqqa. Now and then, I eat a few morsels of bread also. People here have a strange sense of things and a strange disposition. I am just whiling away the fast, but they accuse me of non-observance of this holy ritual. They should understand that skipping the fasts is one thing, and whiling them away is quite another.”

He never spared himself from self-criticism. He writes: “I have learnt to enjoy even my griefs and insults. I imagine myself as a different entity, separate from myself. When a fresh misfortune befalls me, I say ‘well-served! Ghalib receives another slap on his face. How proud he was! How he used to brag that he was a great poet and a Persian scholar, without a peer far and near! Well, deal with the money-lenders now.’

“But how can this shameless fellow speak? He borrowed money left and right — wine from the cellar, flowers from the florist, clothes from the draper, mangoes from the fruit seller, and money from the creditors. He should have realized that he had no means to repay the debts!”

He had occasional outbursts of temper. When his publisher inserted some other poets’ lines in his collection, he exploded: “I do not know the bastard who has inserted into my diwan the verses that you have sent me. May this scoundrel, his father, his grandfather, and his great grandfather, right back to his seven adulterous generations, be damned.”

Ghalib also knew his worth. When somebody asked him for his postal address, he cut him down to size: “Asadullah Ghalib, Delhi will be enough.” So it was. And is today. Delhi is known as the city where Ghalib lived and died.

Found and lost

Kashmiri Muslims love the name Ghulam Mohammed. At least one in every ten, from that of the one time chief minister, Bakshmi Ghulam Mohammed, to the humble boatman who plies a shikara, answers to it. So every other boy goes by its shortened version, Gulla, till he becomes an adult, grows a moustache and takes a wife. Gulla then becomes Ghulam Mohammed.

Padma Sachdeva, celebrated Dogri poetess and writer of short stories (she won the Sahitya Akademi award for literature in 1991 and is a Padma Sri) has used the name to tell the tragedy that has befallen the valley of the Jhelum. The title of her new collection of short stories is Where has my Gulla Gone?. It is also the title of the first story and sets the tone for the others: the Kashmir that was in the good old days of the past when there was peace and plenty and the turbulent, blood-soaked Kashmir of today.

In the opening story there are two Gullas, a mature adult and a boy of five. The author meets them in the hospital where she is convalescing. The elder one adopts her as a moji (mother). Once he naïvely asks her if Hindus really call cows their mother. Equally naïvely, she replies that they do because like a mother a cow gives us milk to drink. (It doesn’t occur to her that so do buffaloes, yaks, camels, goats and sheep). The younger mulla gets attached to her because she gives him a packet of biscuits every day. Everyone loves everyone. And suddenly, lotus flowers that grow in the Dal lake turn blood-red because humans have taken to the AK-47 to spill each other’s blood. It is a highly emotive story (as are the others), overloaded with soppy sentimentalism. Padma does not believe in understatement, malice, satire or irony which are essential ingredients of modern short stories. She is a poetess oozing with the milk and honey of human goodness. She should stick to her imposing verse.