William Baker and John Burke, perhaps the earliest commercial photographers of the North-West Frontier, seemed equally adept at carting photographic paraphernalia to war zones, upper-class homes and gardens and in setting up their studios at Peshawar and Murree. In From Kashmir to Kabul, Omar Khan provides a fascinating account of the work of these two men and an integral aspect of British rule - its war machine. In 1861, William Baker, a retired army sergeant, started photographing in the area between British India and what was at that time Afghanistan (present-day Pakistan); some years later, he was joined by John Burke, a "teenage assistant apothecary from the Royal Artillery" and soon "as the art of war became more and more mechanical, so did the artillery of the war-illustrator," Khan wrote. The two produced panoramic, barren landscapes keeping in mind to carefully position soldiers, both British and 'native', resplendent in their uniforms.

There was, however, much more to record than war and strife and in the early years of the 20th century, the ruling monarch of Afghanistan, King Amir Habibullah Khan, set the pace. Like many Indian rulers of the princely states, he was a keen photographer and a patron, inspiring Afghans who could afford the expensive hobby. In a recent issue of the photography magazine, PIX, on Afghanistan, edited by Rahaab Allana of The Alkazi Collection of Photography, photographer Farzana Wahidy draws attention to the fact that the medium "has varied in tandem with different regimes - from a focus on kingdoms and the landscape to communism, civil war, the Taliban, and finally, the current period of rising democracy." In other words, the camera faithfully recorded Afghan life in minute detail. Though the visual arts suffered heavily at the hands of the Taliban - the irreparable and mindless damage to the Bamiyan statues being a case in point - and photography went underground, it resurfaced at the beginning of the 21st century. While media reporters armed with state-of-the-art equipment brought about an invasion of another kind of the wounded land, something else was going on as well. As images of a post-Taliban Afghanistan flooded the international press, local practitioners and domestic photographers were also hard at work. The camera clearly had a dedicated following in the country, and its popularity was soon in evidence.

That it has not been easy for practitioners of the art was made amply clear to Akshay Mahajan and Tanvi Mishra, who went to Kabul with the express purpose of gleaning images for PIX. Through the Kabul Photography Workshop, aspiring and established photographers were trained to work on the photo essay. Soon, the dramatic, the quotidian, and the prosaic were visually recorded, each introduced by a brief essay describing the intention of the photographer. While most were interested in contemporary subjects, three photographers chose to delve into archives, producing two absorbing essays. In "Years of Forgetting", activist-academic Mujaheda Khowajazada documents changes in women's dress, choosing images to go with the socio-political phase of the country's development. In the early part of the 20th century, King Amanullah Khan was a modernizer and his wife, Queen Soraya Tarzi, tried to bring women out from behind the veil. Soon, a reactionary uprising followed, but not before photographers had managed to depict the Westernized Afghan woman, dressed in the style of Paris salons. Under the forty-year rule of the last king, Mohammed Zahir Shah (1933-1973), while factionalism continued, a parliament was established, free elections were introduced and women had more rights and freedom. Expectedly, under the first democratic ruler, women routinely wore Western-style clothes and continued to do so through the Soviet occupation and under President Najibullah. Khowajazada's juxtaposition of a young woman in a short skirt and tights in the early 1990s with the fully-covered women of the Taliban years more than justifies her belief that what women wear becomes symbolic of the rhetoric of power and dominance.

Interestingly, though nobody looked at the work of William Baker and John Burke, there is a continued interest in camera equipment of the initial years of photography. An essay on the box camera in Afghanistan informs us that the region is one of the last where such an object was in use until very recently. Lukas Birk and Sean Foley introduce the reader to the antiquated wooden instant camera called the ' kamra-e-faoree'. It is a handmade device that contains both camera and darkroom within one large 'contraption' and has been used by generations of Afghans to take identification mugshots. During the Taliban phase, as photography was banned, several photographers had to either hide or destroy their equipment. Post 2001, there was a revival of the box camera and the sturdy equipment saw a new lease of life. However, the authors found that over the last decade or so, its popularity declined, and hence the relevance of documenting the life and work of those who still used this interesting device. The last practitioners were tracked down, and not only were their work recorded but Birk and Foley also learnt how to build and use the camera.

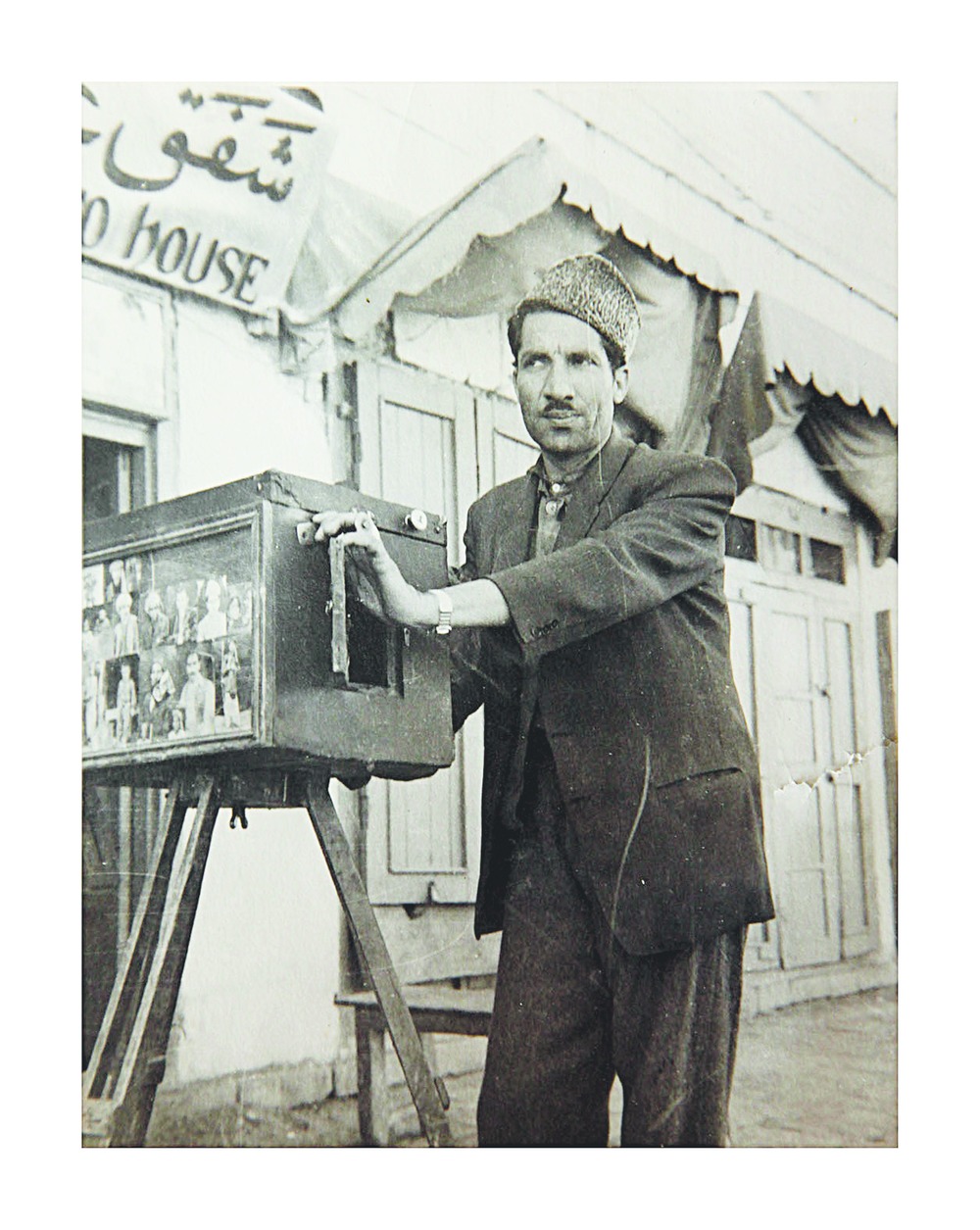

It was during the reign of King Zahir Shah that the photographer Abdul Samad travelled around the area, taking photographs required for the national identity card project. This archival photograph of the 1950s of Samad (picture) posing with his kamra-e-faoree captures the essence of the times. He looks into the middle distance, the hint of a satisfied smile on his lips. While his right hand supports the camera on a stand, his left hand appears to rest on the operating lever. Samad's son, Abdul Satar, was an apprentice in his father's photo shop - but when heavy fighting broke out during the civil war years, he was forced to relocate to Peshawar. Today, Satar has moved into the digital era; until very recently, Qalam Nabi was one of the last two remaining photographers in Kabul using the kamra-e-faoree, interestingly, on a daily basis. That is, the traditional mode coexisted with the rapidly expanding digital market and though there is no information on the age or gender disaggregation of users, it is possible that older men and women were the primary users of a technology with which they were comfortable. This was confirmed by the life story of Izzat Ullah, who was a mere child when he learnt to manipulate the heavy equipment. School in the morning was combined with work with the camera in the afternoon for this son of a refugee from Jalalabad. Izzat Ullah worked in the refugee camp close to Nasir Bagh in Peshawar, "a one-time regular pitch for Afghan box camera photographers." His young age and use of the more familiar box camera was a distinct advantage in a heavily gender-segregated society, families preferred him to photograph women rather than the older men photographers.

The kamra-e-faoree is clearly an Afghani memory from the past whose effacement is alarmingly threatened not only by the digital age but also by the fact that "Facebook and Instagram have become powerful tools of exchange." Yet, though the mugshot was its tour de force, a look at the emotions expressed in many of these confirms that selfie addicts could learn much from these practitioners. Their careful compositions and elaborate yet compact darkroom work can only confirm that quickies are no match for the personalized engagement between the subject and the taker of an image.

karlekars@gmail.com