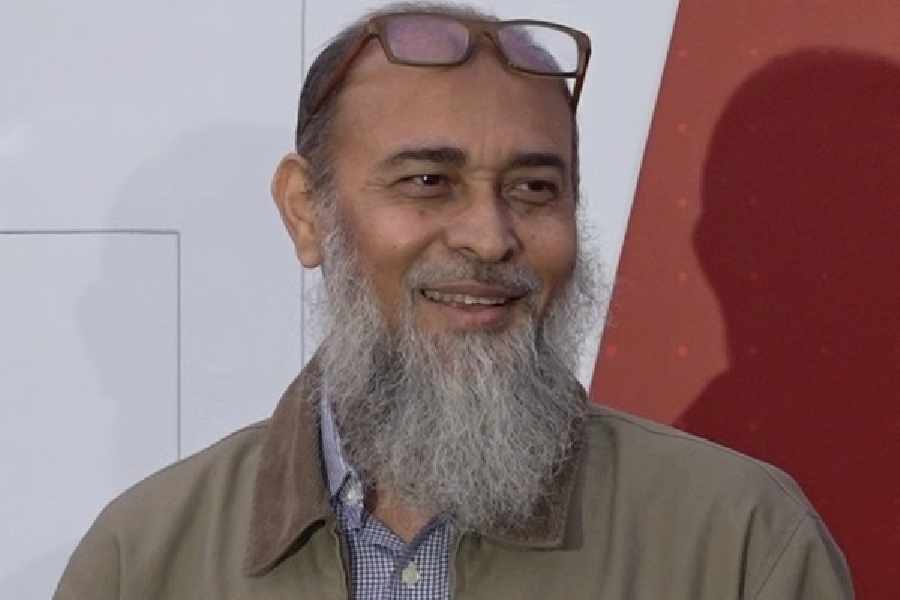

Shahid Siddiqui’s memoir, I, Witness: India from Nehru to Narendra Modi, is more than an autobiography. It is an unconventional story of India’s public life by someone who decided to give up his flourishing academic career at Delhi University as a lecturer of political science to revive his father’s Urdu newspaper, Nai Duniya, in the 1970s.

Breaking with established conventions of postcolonial Urdu journalism, Siddiqui gave a slightly different direction to Nai Duniya. He made a conscious attempt to publish news items and reports that focused entirely on the anxieties and the aspirations of post-Partition Muslim communities in an explicitly secular language. This was a deliberate effort to transform Muslim issues into national concerns, especially in the volatile political context of the mid-1970s after the Bangladesh war when Muslims were often alleged to be separatists and pro-Pakistanis. This new form of journalism was very well received and Nai Duniya gradually emerged as one of the most influential Urdu weeklies in the later decades.

Siddiqui’s political ideas were initially nurtured by his father, Maulana Abdul Waheed Siddiqui. It was, however, the legendary Marxist teacher, Professor Randhir Singh, who shaped his world view and activism in politics. Siddiqui was a member of the Students’ Federation of India and, later, of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). However, his political journey was not very consistent. For a considerable period, he was quite close to the Congress, especially during the tenure of Rajiv Gandhi. He joined the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party, and the Rashtriya Lok Dal at different points of his ever-fluctuating political career. Siddiqui is a former member of the Rajya Sabha.

I, Witness (‘witness’ means shahid in Urdu) narrates Siddiqui’s encounters with two very different worlds — the world of high politics, which is governed by an elusive search for a permanent and everlasting power, and the world of common people where the State is seen as a facilitator to achieve upward mobility, collective progress, justice, and recognition. The author talks about those crucial moments when political transactions between the State and the subaltern communities became unpredictable, intense, and even violent. These moments, the book shows, always produce new political equilibriums for normalising the State-citizen relationship. Although the book is not written for academics, Siddiqui’s explanation of Indian politics makes it theoretically attractive.

A close reading of the memoir offers us four crucial insights. First, Siddiqui envisages India as the land of minorities where every social group prefers to identify itself as a relatively inferior entity. This means two things. In a negative sense, the status of inferiority makes it possible for the group concerned to initiate a politics of victimhood. The actual numerical strength is an important but not an essential precondition for achieving ideal victimhood. For that reason, the politics of victimhood always revolves around an evasive notion of historical injustice. There is, however, a positive implication of this politics of minorities. These social groups not only compete in the realm of politics for representation but they also make a great effort to be recognised as beneficiaries of affirmative action policies. Their socio-economic marginalisation thus becomes a point of reference for a positive politics of social justice. The overlap between victimhood and social justice, in other words, determined the contours of the political discourse, especially in the post-Mandal era.

The role of emotions and forgetting is the second relevant insight. Siddiqui reminds us that Indian political realities cannot be understood without giving adequate attention to the emotional investment of people in politics. The defeat of Indira Gandhi in the 1977 elections and her subsequent victory in 1980 in just a span of three years show that Indian voters do not envisage electoral transactions merely as a professional activity. Their view of politics is also guided by emotive pleas made by political elites. This is also true of the idea of forgetting. Siddiqui recalls how the 1965 India-Pakistan war intensified anti-Muslim rhetoric, especially in northern India. Similarly, the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 led to an atmosphere of hopelessness. These critical events were intentionally overlooked by common people to normalise the situation. It underlines the fact that Indian communities have a strange tendency to give up traumatic memories collectively for the sake of a constructive future.

Third, Siddiqui tries to conceptualise what he calls India’s ethos or “Bharat ki Atma”. Defining himself as “Muslim by faith, Hindu by culture, Indian by conviction and global by outlook”, Siddiqui highlights the fact that it is impossible for any Indian to stick to any one fixed characterising attribute about his/her identity. This inevitable plurality has a unique electoral-political function. It is true that the politics of identity requires caste and religious affiliations to carve out a space for itself in the realm of electoral politics. It does not, however, mean that political parties ignore the segments of voters who do not constitute their core support base. This peculiar requirement forces the political parties to accept inclusiveness as a stated principle (at least in theory).

Finally, Siddiqui evokes democracy as a political value — not only as an ideal, which is accepted by all political forces as the ultimate form of government, but also as a powerful tool that protects the interests of the most marginalised groups and communities. He writes: “the greatest contradiction lies in the fact that this democracy has worsened caste, religious and regional divisions… but it is through the same contrast that independent grassroots leaders have emerged overnight as saviour of particular caste or sub-caste by deepening caste and communal divide.” This seemingly paradoxical character of Indian democracy, in a way, underlines its distinctiveness.

These four insights — perceived inferiority by social groups, emotional investment in politics, a multidimensional Indian identity and the recognition of democracy as a value — stem from a handsomely woven narrative. On these pages, we meet a cheerful Jawaharlal Nehru, the iron lady, Indira Gandhi, the young, dashing Rajiv Gandhi, the poetic A.B. Vajpayee, the intellectual, Manmohan Singh, the leaders of the masses, Mulayam Singh and Mayawati, and, finally, Narendra Modi, who did not hesitate to answer Siddiqui’s tough questions. The book also provides an observer’s account of a few critical episodes of India’s political history — atrocities committed during the time of Emergency, the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the Shah Bano controversy, the killing of Rajiv Gandhi during an election rally, the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the Indo-US nuclear deal and so on.

I, Witness, in this sense, is not a book to be reviewed; it is an intentionally unfinished project, which invites us to draw our own meanings of Indian politics.

Hilal Ahmed, Professor, CSDS, New Delhi