Much like a book that cannot be judged by its cover, the significance of a speech can sometimes not be gauged by the screaming headline it generates.

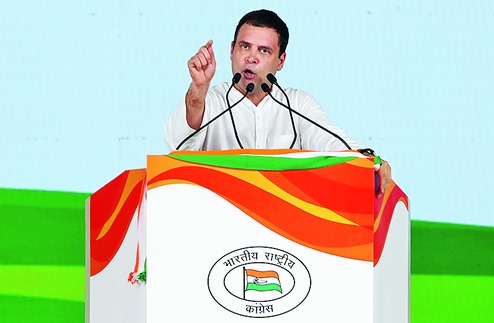

Towards the end of a long-drawn-out campaign for the Karnataka assembly elections, the Congress president, Rahul Gandhi, briefly displaced Prime Minister Narendra Modi on television screens. Rahul Gandhi made waves because he had, the news channels said, unambiguously declared his ambition to be prime minister.

The May 8 "declaration" provided fodder for long hours of discussion in television studios and gave the prime minister yet another handle to mock the Congress chief. Addressing election rallies in different parts of Karnataka the next day, Modi said a person declaring himself eligible for the post of prime minister was the "height of arrogance" and that making such a declaration was "a blow to the democratic system of the country." He even likened Rahul to a village bully who jumps the queue before the arrival of a water tanker and "walks straight to the front of the line to claim his water..."

Given his rhetorical flourishes that are often economical with facts (such as his claims about Jawaharlal Nehru mistreating Field Marshal Cariappa and General Thimayya where he got even the dates wrong), the prime minister's claim about Rahul's alleged claim was hardly a surprise. Besides, in this case, Modi was not delving into history but relying on the day's headlines.

The fact, though, is that Rahul Gandhi made no grand, unilateral declaration about his prime ministerial ambitions. His remark on the subject came as a reply to a persistent questioner at the end of an hour-long interaction with a selected audience in Bangalore last Tuesday.

The interaction between Rahul and a group of Bangalore citizens took place after he inaugurated the Samruddha Bharat Foundation, a platform that aims "to propagate liberal, secular and republican values." Asked by a member of the audience whether he was willing to be prime minister in 2019, Rahul first replied, "That depends on how well the Congress party does." When the questioner asked about the prospects in case of an alliance winning the next election, he said, "If the Congress party is the biggest party, yes."

That was all - a simple answer to a straight question that, far from being arrogant, was hemmed in by ifs and buts.

That one throwaway line garnered all the publicity and little was written or aired about the Bangalore meeting itself. It is only on viewing the entire interaction - which is freely available on the internet - that it becomes clear that Rahul Gandhi spoke of many things that day of far greater import than the prospect of becoming prime minister.

More than the easy confidence he exuded or his articulation of the Congress's vision, it is Rahul Gandhi's jargon-free ideological clarity that makes the Bangalore talk a significant milestone in his long and meandering political journey.

Perhaps the most interesting of his many observations that morning pertained to the question of elections. Much has been written in the last four years about the Bharatiya Janata Party's new-found passion to win every election it contests. We are all witness to how the Narendra Modi-Amit Shah duo has turned the party into a relentless election winning machine. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh usually provides the grass-roots network while the BJP top brass mobilizes massive resources to unleash a propaganda blitzkrieg and acquire new allies through a combination of blandishments and threats. When the BJP has failed to win enough seats in a state assembly, it has swiftly managed to put together a government through superior "managerial skills". Few other parties have been able to match the indefatigable zeal of the post-2014 BJP.

Rahul Gandhi sought to explain just why. When a member in the audience spoke of the manner in which the independence of institutions including the Supreme Court - was being eroded in recent years, Rahul said this phenomenon was not confined to just India. Forces such as the RSS in India and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia were doing the same thing: using elections to win power, and then using that power to capture all institutions.

Elaborating, he said, "So the RSS and the Muslim Brotherhood do not see elections the way we see them. We see elections as a way of carrying democracy forward. We are perfectly happy to win an election and we are okay with losing an election, and then we win again. We don't have an existential crisis when we lose an election."

The RSS and the BJP, on the other hand, see elections "as a way to enter government and once they have entered, they want to capture every single institution in India... the idea is that one more cycle like this and then we don't need democracy. We will then close the door from the other side and then the people of India can shout and scream as much as they want, it doesn't matter because institutional capture has taken place."

To another question on the growing incidents of anger and violence in the country and whether the silence of the prime minister contributed to it, Rahul said, "When the leadership of the country ignores certain types of behaviour, people who otherwise wouldn't have the guts to do certain things suddenly believe they can. You can see it in Uttar Pradesh, you can see when a Yogi Adityanath becomes chief minister, lot of forces who would simply not raise their head, start to do so. I think there is a connection between the type of politics that Mr Modi and Mr Adityanath do and the type of anger and violence you see."

Rahul then went on to offer an important insight about the regressive nature of this politics. He said, "You can run a government in two ways - you can run it on memory or you can run it on imagination. You can run it on the past or you can run it on the future. And you can run a country like that too."

And today, all the discussions taking place are only about the past - "who did what, why did it happen... there is almost no conversation about the future." This obsession with the past was part of a design. For one, it diverted attention from real problems. But it also stemmed from a fear of democratization. "There is a feeling among a lot of people in India that large masses of people are becoming empowered. And for these people who have always had power, it is a disturbing thing, they feel uncomfortable that a huge amount of people in India can start to compete with them, can start to have a place under the sun. There is a sort of feeling that let's go back to the past, why have all these forces been unleashed?"

Perhaps because he was speaking at a closed-door meeting with like-minded liberals, Rahul was far more candid and insightful in his observations than at a public rally. But his words evoked a special resonance in the light of events taking place in north India when Karnataka was in the midst of the election campaign.

Aggressive young men tried to barge into Aligarh Muslim University to remove the portrait of Muhammad Ali Jinnah from the students union hall leading to clashes; another lot of men sought to prevent Muslims from offering namaz on open grounds in Gurgaon; a Dalit activist was shot dead in Saharanpur where upper caste men were celebrating Maharana Pratap's birth anniversary, while on the same day another right-wing group tried to rename Delhi's Akbar Road after Maharana Pratap.

Every time the BJP wins an election, the zealots at large become even more aggressive on the ground and the RSS more determined to drag India into the quagmires of the past. By understanding the drive and the design of his principal adversary, the new Congress president has shown a measure of political astuteness and ideological acuity that is far more important than any prime ministerial ambition - and certainly more useful in the long battle that lies ahead regardless of what Karnataka throws up tomorrow...