MY NAME IS RADHA: THE ESSENTIAL MANTO Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon, Penguin, Rs 599

Saadat Hasan Manto, one of the most well-known writers in Urdu in the first half of the 20th century, must be a favourite subject of translators, if the number of translations of his works that have come out in the last few years is anything to go by. Bitter Fruit: The Very Best of Saadat Hasan Manto , translated and edited by Khalid Hasan came out in 2008, followed by Manto: Selected Stories, translated by Aatish Taseer in the same year. Saadat Hasan Manto: Bombay Stories , translated by Matt Reeck and Aftab Ahmad, was published in 2014. And now there is Muhammad Umar Memon's translation. Even if translation is taken to be the art of failure, heroic translators do try their hands at the almost impossible task of capturing the nuances of a particular language in another one, and fail in varying degrees. Memon's translation would rank somewhere between the choppy smartness of Hasan's and the polished smoothness of Taseer's. It is lucid, if unimaginative. One can perfectly understand what Memon is trying to convey when he writes, for instance, "I rushed over to her, lifted her rear end [my italics] and pushed her out" ("Recite the Kalima!"). But, surely, he could have come up with something better than "rear end", which makes the woman being thrown out of the window seem like a bundle?

In the manner of most Indo-Anglian authors writing today, Memon provides no footnotes for better-known Urdu words like baithak , jamat-khanas or mazaar ; rightly so, since most non-Indian readers would be able to make out the meaning from the context even if they are not familiar with the words. He keeps Urdu poetry, where it is quoted by the characters, in the original, and gives the meaning in the footnotes - which, again, add to the value of the translation by letting readers savour the loveliness of the Urdu words. Some footnotes, however, can be misleading. For example, in the short story, "Barren", a character talks of the "Dipty Sahib", and Memon says in the footnote that "dipty" is the "Urdu pronunciation of deputy". In using 'deputy' like this, Manto is trying to capture the cadences of the language as spoken by the character, who is a driver. Do all Urdu speakers, past and present, irrespective of their background and education, pronounce 'deputy' as "dipty"? In the story, "Ram Khilawan", the eponymous dhobi calls Byculla (in Mumbai) "Byekhalla" for the same reason - there too Manto tries to record the washerman's spoken voice as he natters away endlessly. In this case, however, Memon does not specify Byekhalla as the 'Urdu/Hindi pronunciation' of Byculla.

With so many translations of Manto available in the market, any new translator has to explain why his is different. Memon sets out to do this in the introduction, which he chooses to call, a bit pompously, the "Preamble". Manto has often been stereotyped as a writer specializing in Partition and prostitutes. Memon says that his selection "seeks to correct this reductionist impression of a writer who is concerned more with the unique substance of his characters than with social problems and political events as the mainstay of his creative work". It is true that political events such as Partition are no more than backdrops in most of Manto's tales. His interest is not so much in the historical event per se as in the way it serves to bring out certain character traits of the people he is portraying. However, this fact would be evident in any translation, not just in Memon's.

As to the accusation of obscenity often levelled against Manto with reference to his engagement with fictional prostitutes, nobody can defend Manto better than he himself does, in the pieces called "Ismat-Faroshi (Prostitution)", and the one translated here as "I too Have Something to Say", from the author's collection, Mantonuma (which is spelt this way and also as Mantonama in the book). Memon's defence, in contrast, sounds rather prudish. While discussing the short story, "Spurned" (which features later in the book as "Scorned"), Memon shows how Manto leaves the readers to draw their own conclusions as to why Saugandhi has chosen to be a prostitute. While guessing the reasons, Memon says that one can suggest in a "devilish vein" that "she turned tricks simply because she loved sex". Indeed, not many prostitutes would have the luxury of choosing the profession because they love sex. But what is wrong if she does so? Manto writes, and Memon points this out: "Every limb of her body yearned to be worked over, to exhaustion, until fatigue had settled in and eased her into a state of delightful sleep." Saugandhi appears to belong to the ranks of the lucky few who like the job they do. She does not seem to think that there is anything wrong, or devilish, in the enjoyment.

Manto adds, "Although her [Saugandhi's] mind considered sexual intimacy patently absurd, every other part of her body longed for it." The first part of the sentence does not seem to be intended to convey Saugandhi's reluctant participation in sex, although Memon would have us believe that. The book's concluding chapter by Memon, titled "Recounting Irregular Verbs and Counting She-Goats: Manto and His Alleged Obscenity", is an attempt by the translator to 'defend' Manto - an attempt in which he enlists, quite redundantly, the help of Kundera and Neruda - by suggesting that his prostitutes do not enjoy what they have to do.

In planning his defence this way, Memon can be accused of thinking along the same lines as those of Manto's critics who objected to his writings on grounds of morality. Why is Memon so eager to stress that a prostitute's mind is not in the sexual act? Is it because it would be difficult to think of her as a 'good' woman if she is shown as enjoying the lovemaking? In the sentence quoted at the beginning of the paragraph, Manto does not say that Saugandhi shut off her mind to steel herself every time she got into the act. Rather, he directs attention to Saugandhi's capacity to be involved and uninvolved at the same time, and to her readiness to let the body cancel out the mind during love-making (these qualities must have made her a good professional lover). Whatever her opinion on sex might have been in her contemplative moments, when it came to the act, she participated full-bloodedly. If this makes her seem contrary, well, this is how women and men are. Manto's success as a writer lies chiefly in his ability to bring out the contrariness of characters - and of human beings - so sharply.

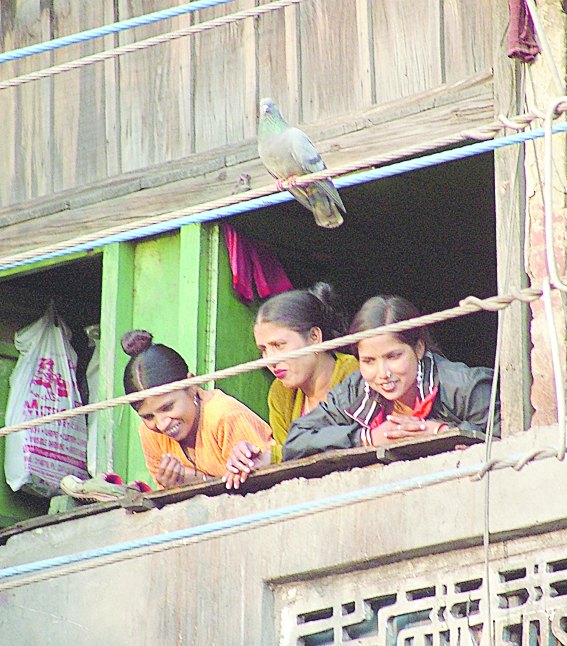

In "I too Have Something to Say", Manto draws a parallel between the storyteller and the prostitute. The similarity lies in the fact that both have been plying their trades from the beginning of time. And, in all probability, they will stay on in their jobs till the end of time. One of the reasons behind their resilience as professionals might be their shared ability to weave fictions - about life, in case of the storyteller, about love, in case of the prostitute - for the reader and the client, respectively, and to believe in them so strongly that the audience too willingly suspends disbelief to have faith in the myths they are served with. The fabulist and the prostitute replace reality with a painted, tinsel world, which is alluring because it is beautiful.

That beauty is the poetic truth, which is different from the truth of history or of morality, in its potential to accommodate contradictions. So, in the story, "For Freedom's Sake", people start feeling buoyant in the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy -the "strange excitement" that grips them is compared to the "gushing energy" of the milkmaids of Amritsar rushing through the city with their baskets carefully balanced on their heads; in "A Tale of the Year 1919", the narrator would like to have his audience believe at first that two famous prostitutes had killed themselves to stop the British rulers from sullying their honour, only to confess later that "those bitches" had heartily entertained the sahib-logs as per instructions; in the title story, "My Name is Radha", the feisty starlet who quickly strips off the pretensions of a seemingly upright superstar, declares with aplomb, "Once I've made a mistake, I stick to it." Manto's fiction is full of pious bawds, criminal-minded ascetics, caring murderers, conservative progressives and honest liars. Who can say with conviction that a pimp's identity as a pimp is a more important part of his character than his religiosity? Or that a murderer cannot be sincere in his or her love? Manto's characters always act contrary to expectations and meticulously subvert all efforts to categorize them.

"Essential" is a particularly unfortunate word to be used in relation to an inveterate ironist like Manto. By subtitling his book as The Essential Manto , Memon may also be trying to suggest that his is the ultimate compilation. The infelicities in the translation would make any such implied claim hard to sustain.