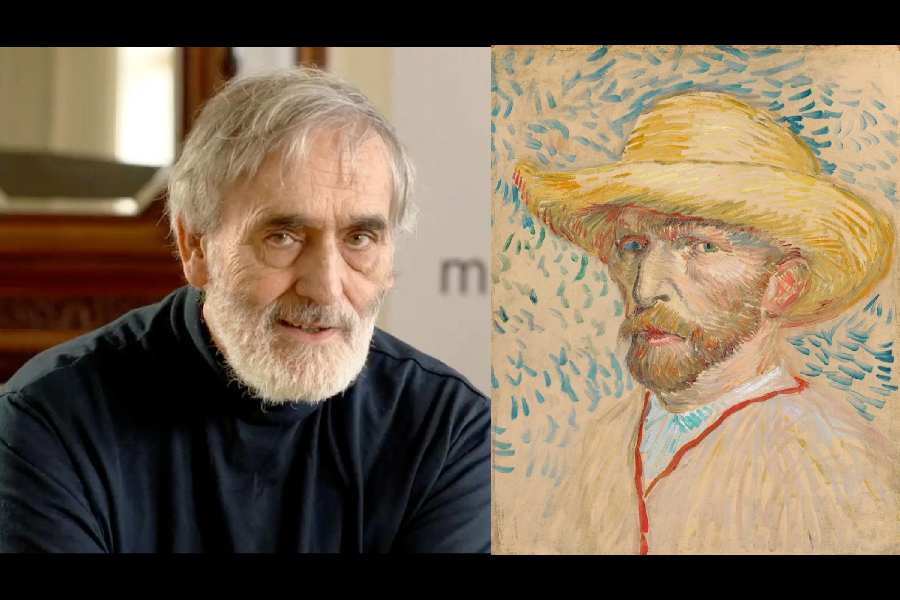

In the past, I’d seen various Western classical ensembles when they’d come to Calcutta but never while visiting the West had I made it to a concert by a full philharmonic orchestra. The occasion for which I fortunately got a ticket was the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra performing two long pieces: Ausklang by the contemporary composer, Helmut Lachenmann (picture, left), and Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No.11 in G-Minor — ‘The Year 1905’. The venue of the concert was as interesting for me as the actual performance. The architect who conceived the Berliner Philharmonie was Hans Scharoun; his design of the concert hall was ground-breaking and became a model for other major concert venues, including the Sydney Opera House.

The Philharmonie stands right across the road from another iconic West Berlin building, the New National Gallery by Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe. In contrast to the sparse, matte-black grid of the Gallery, the top of the Philharmonie’s cladding of gold-anodised aluminium catches the last of the evening sun like a range of high mountains. Inside, a typically spare and open mid-20th-century space greets the visitor, the detailing of the doors and entrance barriers making direct salutes to Bauhaus design with not a plaster curlicue in sight. The concert hall may produce all kinds of music — Baroque, Romantic or Modern — but a firm goodbye has been bid to the over-decorated 18th and 19th centuries, the door slammed shut on the more recent, ghastly Hitlerite aesthetics.

From the foyer, you wind your way up a series of stairways and find your way into the hall itself. This was one of the first auditoriums where the seating was organised in the ‘vineyard style’ with asymmetric terraces of seats rising all around the central music stage. The capacity is just under 2,500 people and the audience seems to comprise largely of people above 40 but with a few younger listeners as well. Any notion of dressing formally is quickly dispelled — this is Berlin at the end of summer and for every evening gown and three-piece suits there are about 30 people in normal streetwear, jeans, hoodies and even shorts. There is, however, no such casualness in the attire of the musicians as they file in to light applause. The women are in formal, occasionally colourful, clothes, but the men are all fully suited in tails, their feet sending out pinpricks of light from highly-polished black shoes.

Vladimir Jurowski, the conductor, walks out to heavier applause and takes some time to explain the connection between the two pieces that are about to be performed. He walks off again as the lead violinist stands up and saws off a note to the nearly hundred musicians. There is a brief melee of tuning sounds from deep base to high tinkle and then silence. Jurowski comes back on stage accompanied by the piano soloist, Pierre-Laurent Aimard. Applause. Jurowski stands on the conductor’s podium and stretches himself tall and straight. The violinists raise their bows. Silence.

Lachenmann is regarded as a ‘difficult’ composer even in the rarefied precincts of what is often called ‘New Music’. To someone new or not yet engaged with it, the series of assorted sounds may sound like a compilation of random squawks, grunts and grumbles that seem to go on forever and beyond. But if you are someone who’s developed a taste for atonality and dissonance, this accumulative marking of the blank canvas of silence takes on a hypnotic quality, the constellations of sound enveloping you and refusing to let you go. I had heard Karlheinz Stockhausen, one of the great figures of New Music, when he came to Calcutta in the 1980s but never before had I experienced this kind of aural stimulation at this grand yet intimate scale.

In the interval, our motley group of friends was divided. Some were glad the nail-on-blackboard torture was over, while the rest of us felt elated at having experienced something truly fantastic. All of us were curious to see how the comparatively mainstream and old-fashioned Shostakovich would now sound. When the orchestra came back on stage, it seemed to have many more members. As the music progressed, you understood why. A cursory trawl through the internet tells you that Shostakovich had written this symphony in 1957, as a piece to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution of 1905. The composer had spent a period of time in disfavour as Stalin had wrinkled his nose at his music but he was reinstated after the dictator’s death. This and other pieces by Shostakovich are often described as soundtracks for films that didn’t exist and listening to his 11th, you can see why. For a newbie like myself, the visceral, haptic feeling created by the massed thrum of the cellos and the thundering of the drums was a totally new experience. Also an eye-opener was how, when you see a concert live, the unspoken narrative aspects of any piece come through so vividly.

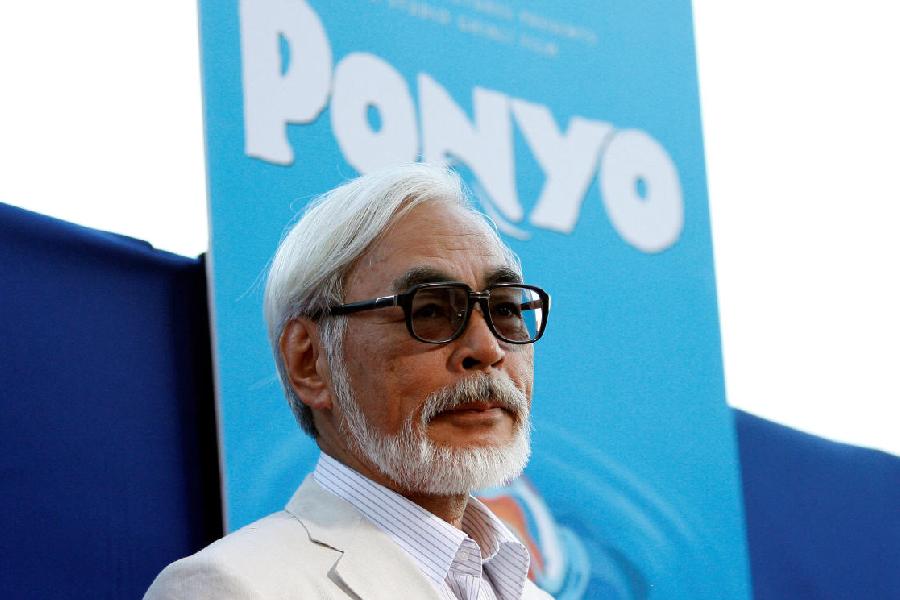

Listening to the Shostakovich symphony, I was suddenly reminded of the show of paintings I’d seen earlier this summer at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Anselm Kiefer, one of the major painters to come out of post-War Germany, has always said he is deeply indebted to van Gogh. As a young artist, Kiefer even undertook a journey in the early 1960s following van Gogh’s travels across Holland and France. The show at the RA juxtaposes huge oil and mixed media canvases by Kiefer, works that reference the Dutchman, against some of van Gogh’s best-known works.

The first thing that hits you is that you are looking at two entirely different activities: one is a painter working on his canvases and drawing sheets, someone who loses all awareness of himself as he paints; the other is a man performing the act of painting-construction, constantly watching himself as he applies material to surface. Reading various reviews later, I saw they shared my observations: here was an often impoverished man eking out a painter’s life, dependent on money sent by his brother, living and working in a schizophrenic condition of economic and social scarcity, everything hard to get — paints, food, love — and the abundance (especially later in his short life) of the overwhelming beauty of rural France; and here, on the other hand, was this 20th-century man who’d grown up in the full support of his bourgeois family during the post-War German economic miracle, made it good fairly early in life as a highly talented and innovative painter-provocateur and, then, continued to grow into rarely paralleled success as a megastar artist. By the time he’s 37, the age at which the gunshot kills van Gogh, Kiefer is a rich man; soon after, he’s able to buy whole factory compounds to convert into his working space; the scale at which he works now, he needs a bicycle to ride from canvas to canvas. A sparse economy of means and an absurd, often obscene, plenitude of means clash against each other on the walls of the old Academy. It’s not that Kiefer’s Imax-size paintings are nullified, but they are definitely put into a context that startlingly reduces their heft on the weighing scales of artistic endeavour.

At the concert hall in Berlin, something similar happened but with a twist. It was Kiefer’s exact contemporary, Helmut Lachenmann, often derided and ignored, a marginal among marginals (if you look at the whole universe of Western classical music), who seemed to provide the apt soundtrack for the van Gogh paintings, and Shostakovich, unfurling his entire musical might with full State support, basking in the light of his own self-perceived greatness, who best matches the grandiose expressions of Anselm Kiefer.