Satyagraha is one of the highly misused, distorted and misrepresented political metaphors in the Indian context. Governments, political parties, social movements, non-governmental organisations and even the corporate world are obsessed with it. There is a strong assumption that satyagraha is a ‘tolerable’ technique to assert powerlessness in a peaceful manner, simply to register one’s victimhood and relative marginalisation.

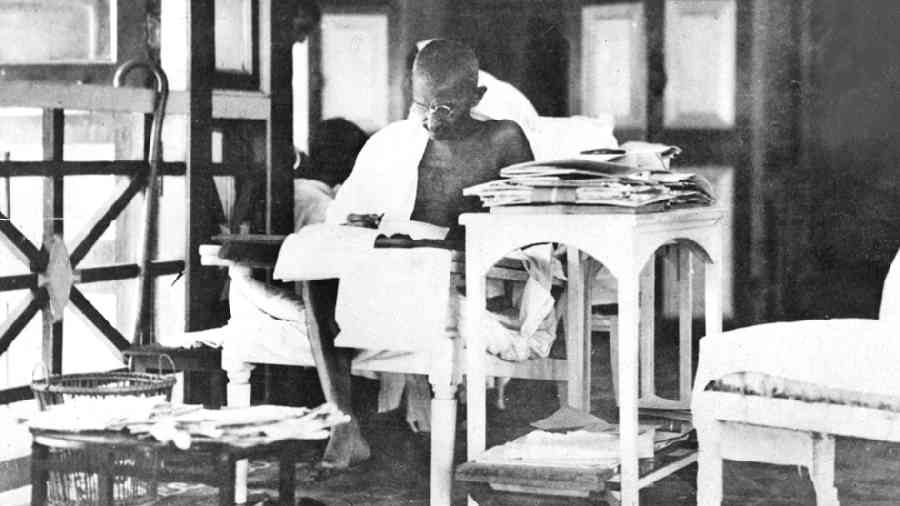

This uncontested acceptability of satyagraha is inextricably linked to a particular image of Gandhi. He is invoked as an old, ever-compromising, exhausted, and non-assertive personality who rationalises satyagraha as a weapon of the weak. The popular Hindi saying, ‘Majburi ka naam Mahatma Gandhi’, hence, gets justified.

This rigid imagination of satyagraha is highly problematic. It goes against the central premise of Gandhian praxis, which is based on profound philosophical thinking and deep adherence to social and political transformation. Gandhi’s satyagraha is a radical programme of political action based entirely on the purity of individual commitment. The retrieval of Gandhi’s own explanation of satyagraha, in this sense, is very relevant to commemorate him as an original, creative and courageous political thinker.

Gandhi, we must note, is a difficult practitioner of political ideas. He always takes unthinkable positions on social and political issues while celebrating his inconsistencies. According to him, “I am not at all concerned with appearing to be consistent… When anybody finds any inconsistency between any two writings of mine… do well to choose the latter of the two on the same subject” (Harijan, April 29, 1933). This crucial advice becomes more complicated when Gandhi categorically gives priority to his acts and actions over his writings. He says: “My writings should be cremated with my body. What I have done will endure, not what I have said and written” (Harijan, May 1, 1937). These provocative statements also underscore Gandhi’s carefulness. He avoids any generalisation of concepts, such as swarajya and satyagraha, even though they were central to all his experiments and practices.

We must, therefore, avoid attempts to recover any ‘real’ Gandhian meaning of satyagraha. Instead, we need to do two things. First, we must read Gandhi the way he would like to be read; and, second, his writings must be recognised as a specific form of political action. This possible re-reading of Gandhi, in my view, might help us discover a different explanation of satyagraha.

It is worth noting that Gandhi used the term, ‘passive resistance’, in describing his initial struggle in South Africa. However, after some time, he found this expression to be rather misleading. This led to the search for an appropriate term. According to Gandhi, his relative, Maganlal Gandhi, suggested the word, ‘sadagraha’ (firmness in a good cause). Gandhi liked the word, but he did not find it linguistically appropriate. He amended it and eventually it became ‘satyagraha’.

Gandhi, however, does not stop here. One finds at least three fundamental differences between passive resistance and satyagraha in his writings. First, passive resistance is a strategic move taken by a political group to achieve a larger objective. Satyagraha is not practised as a strategy. Rather, it is an individual quest for exploring an internal ‘truth’. Gandhi writes: “The very nature of Satyagraha is such that the fruit of the movement is contained in the movement itself. Satyagraha is based on self-help, self-sacrifice and faith in God” (Satyagraha in South Africa, 1928, p. 172).

Second, passive resistance is a weapon of the weak because it is based on a hierarchical, competitive, and an ever-conflicting relationship between the weak and the powerful in a given situation. Satyagraha, on the other hand, is the weapon of the strongest. It excludes the use of violence in any shape or form to achieve harmony and peaceful coexistence. Gandhi reminds us: “a Satyagrahi must never forget the distinction between evil and the evil-doer. He must not harbor ill-will or bitterness against the latter. He may not even employ needlessly offensive language against the evil person, however unrelieved his evil might be… For it is an article of faith with every Satyagrahi that there is none so fallen in this world but can be converted by love” (Young India, August 8, 1929).

Finally, passive resistance is based on a possibility that once power is achieved by the weaker group, it might not hesitate to practise brute force as per the contextual requirement. Satyagraha strongly adheres to the idea of the love force. It is expected from a satyagrahi to have complete faith in the doctrine, ‘Truth is God.’ Gandhi argues: “… Such a universal force necessarily makes no distinction between kinsmen and strangers, young and old, man and woman, friend and foe… Love does not burn others, it burns itself. Therefore, a Satyagrahi… will joyfully suffer even unto death” (Young India, February 27, 1930).

This rather idealistic picture of satyagraha as a self-sacrificing technique based on the love force also underlines a very different notion of radical politics. A careful reading of Gandhi’s writings on this subject introduces a few basic preconditions which he identifies for an impactful satyagraha.

Satyagraha in the ‘last instance’: Gandhi makes it very clear that as a political technique satyagraha should not be practised hurriedly. In the Gandhian schema, satyagraha requires careful consideration and thinking. According to him, “Satyagraha is never adopted abruptly and never till all other and milder methods have been tried” (Young India, January 14, 1926).

Satyagraha as self-realisation: Gandhi does not define satyagraha as a kind of political correctness. For him, the objective of satyagraha is not only to question the external exploitative structures but also to make an individual judgment on one’s own belief system and commitment. Gandhi makes a powerful claim: “a person who claims to be a Satyagrahi always tries by close and prayerful self-introspection and self-analysis to find out… whether he is not himself capable of those ‘very evils’ against which he is out to lead a crusade” (Young India, August 8, 1929).

Satyagraha and public opinion: Gandhi recognises the importance of favourable public opinion. He is fully aware of the fact that satyagraha as a technique would become meaningful only if it is supported by strong public opinion. For him, “… a Satyagrahi… must first mobilize public opinion against the evil which he is out to eradicate… when public opinion is sufficiently roused against a social abuse even the tallest will not dare to practice or openly to lend support to it. An awakened and intelligent public opinion is the most potent weapon of a Satyagrahi” (Young India, August 8, 1929).

This Gandhian reading makes it clear that the official programmes sponsored by the governments to publicise good governance or the fashionable candlelight marches led by Opposition parties/ self-claimed liberals asserting victimhood cannot be called satyagraha. There is an element of ‘passive resistance’ in these acts which is often highlighted as a Gandhian technique. This intentional overlapping of passive resistance and satyagraha works in favour of the political class. It becomes easier for the political class to establish Gandhi as an old, useless symbol. Hence, satyagraha emerges as a weapon of the weak, something which Gandhi categorically opposed and rejected.

Gandhi offers us an outline of a radical theory of satyagraha, highlighting its capacity as a political method in different contexts. And he also warns us about the possibilities of its conceivable misuse.

Hilal Ahmed is Associate Professor, CSDS, New Delhi