Man straw

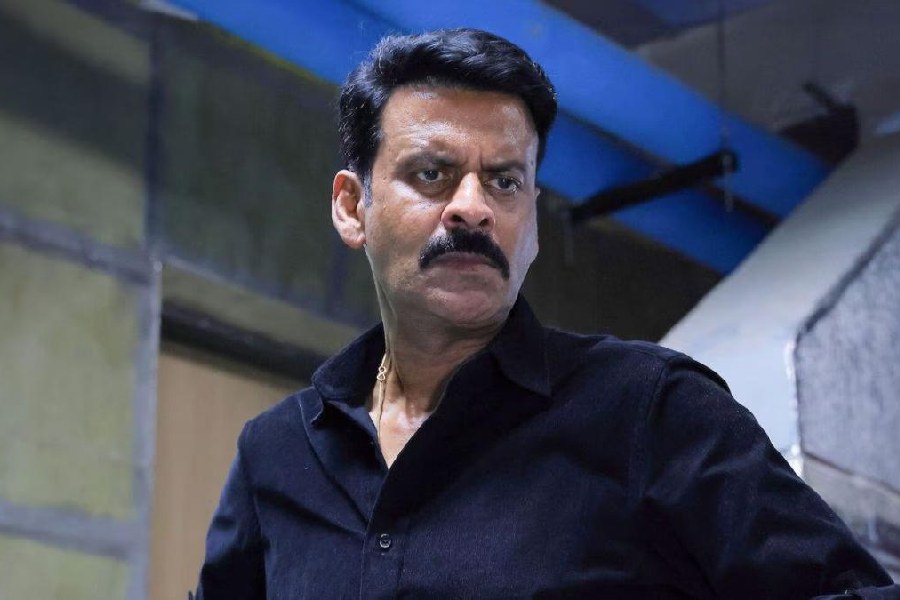

Till November, the man who is widely believed to be behind the attempted assassination of GNLF chief Subhash Ghising, was earning a livelihood supplying drinking water in a couple of old jeeps to the residents of Kalimpong. In Raushey Bazaar, on the outskirts of Dungra district, Chhattray Subba is known more as a social worker than a militant leader, soft-spoken and courteous, often to a fault. The only indulgence in an otherwise spartan lifestyle being his penchant for British army hats and good quality boots and pullovers. The stocky frame with its trademark beard and tilted hat was a sight familiar to all Kalimpong residents. Somewhat of a recluse, the fifty-four-year-old Gorkha leader has few friends and prefers to keep to himself. A man of few words unless, of course, the conversation veers around to his passion - Gorkhaland.

It needed a Subhash Ghising to stoke the fire of a homeland for Gorkhas in the heart of this militant hill maverick, who belongs to the Mongolian stock of the Limboo community. Like Ghising, Subba is a former army man. Born in Kalimpong's Dungra basti, Subba joined the army in 1961 at the age of 16 and rose to be a Naik with the 11 Gorkha Rifles. After retirement, he was content to live off his pension in Kalimpong until he fell under the spell of Ghising in April 1986. The two retired army men bonded instantly. The GNLF chief gave Subba the crucial task of training recruits for the militant wing. Subba went on to head the wing, the Gorkhaland Volunteers' Cell (GVC), Kalimpong division, and later the entire GVC. A strict task master and a stickler for discipline, Subba turned his rag-tag recruits into a force to be reckoned with, despite having limited resources at his disposal. The ingenious fighter once allegedly tried to assemble a 'gorkha cannon' from a hollow telephone post. The contraption literally backfired, with cannon and shot taking off together.

Subba and the GVC were at the forefront of the Gorkhaland agitation. At the peak of the Gorkhaland agitation, the GVC had about 10,000 members. His cadres rampaged about the hills silencing Ghising's opponents and challenging the administration with their acts of sabotage. It was the might of the GVC which forced the state government to reach a settlement with Ghising. But Subba never made the headlines as he preferred to keep a low profile, letting other militant leaders like Ghising hog the limelight. This was Subba's finest moment.

The relationship between Subba and his mentor became strained towards the end of the Gorkhaland agitation. The GVC's alleged atrocities had become more of a liability than an asset to Ghising and he was forced to disband it. Matters came to a head when Ghising settled for the tripartite Darjeeling Hill Accord in August 1988. Subba called Ghising a traitor to the cause of Gorkhaland. 'Ghising made Gorkhas dream of a Gorkhaland yet went on to betray them,' he told The Telegraph last November. 'The supreme sacrifice of thousands of Gorkhas during the GNLF agitation went in vain. Our youths were felled by security bullets houses burnt, women raped and widowed, yet Ghising went on to sign the Darjeeling Accord. He has to pay dearly for this betrayal of his own people.'

Ghising, on his part, branded Subba a 'sarkari stooge'. An embittered Subba contested the first DGHC election as an independent from the Bong-Dungra seat in Kalimpong, ostensibly to bring about 'peace in Darjeeling.' In an interview to a weekly magazine, he said: 'If my dream of Gorkhaland becomes a reality, I will not be there to hanker for any position of power.' He never got a chance to prove that. The DGHC swept the polls.

Subba went into oblivion for a year. He surfaced in 1990 by launching his very own Gorkhaland Liberation Organisation (GLO) 'to launch a fresh agitation for a separate Gorkhaland'. Most of his followers were erstwhile GVC cadres. And it is even said that in a bid to clip Subhash Ghising's wings, the state government had secretly propped up the former militant. But Subba failed to use it for larger political goals as his influence was confined to Kalimpong.

The time could not have been more opportune. A number of political leaders, disillusioned by Ghising and his hill council, throw in their weight behind the GLO. But it soon became all too apparent that Subba was no Ghising. The GLO supremo was quite unable to mobilise what a movement needs in its nascent stages: adequate funds and proper organisation. Subba went into wilderness but would emerge from time to time to make token gestures of resistance.

But disgruntled pro-statehood Gorkha leaders resurrected Chhattray Subba. He was back in the limelight early last year when former GNLF leader from the Dooars, N.T. Moktan, and a host of other disgruntled leaders met him in Kalimpong. Among them was C.K. Pradhan, second-in-command in the DGHC. And the Tinkatharia shoot-out between alleged Naga ultras and Kalimpong police in November last year seemed to signal the birth of yet another militant outfit and yet another rabid hardliner.

Subba insisted, 'The so-called Naga militants killed by the police at Tinkatharia were innocent supporters of the GLO. The police are falsely accusing the GLO of having links with militants in the northeast.' Subba's links with the northeast is of a gentler variety. After leaving the army in 1983, Subba settled in Dimapur, where he met his first wife. Tamangni was a Nepali woman employed with the Nagaland government. She still lives in Dimapur with their 26 year-old son, Goray. Chhattray also has a married daughter living in Nagaland. His second wife, Monika, whom he married in 1996, lives at his Dungra basti residence with two minor children.

Subhash Ghising though, has accused Subba of having close links with underground Nagas and of running camps on the Indo-Nepal border. May be that is why he was charged with sedition and a warrant was issued against the GLO leader after the Tinkatharia incident. Subba went into hiding and subsequently issued an ultimatum to Ghising and his DGHC councillors to disband the Hill Council and join his renewed call for an armed struggle for a separate statehood. Subba set a December 31 deadline for the GNLF leaders to resign or 'face dire consequences'.

Subba may or may not have lived up to his words more than a month after the deadline. What is certain is that Subba on the run and with little political base or acumen will not be able to marshal forces to be a real challenge to his bete noire, Subhash Ghising. His favourite posture has always been sitting all by himself in a meditative trance on rocks near the jungles bordering his village. He could be doing just that in Nepal.

Saturday, 07 February 2026

Saturday, 07 February 2026