ATTENDANT LORDS: BAIRAM KHAN AND ABDUR RAHIM; COURTIERS & POETS IN MUGHAL INDIA By T.C.A. Raghavan, HarperCollins, Rs 699

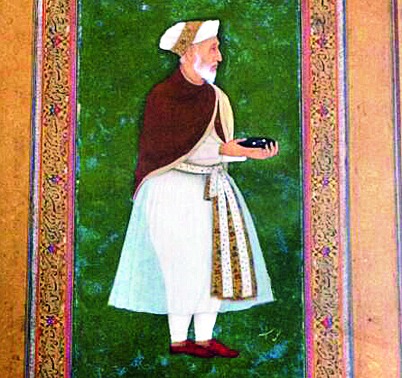

The Mughals, of late, have taken such a thorough beating at the hands of the Hindu Right that a slew of scholars have found it necessary to come to their rescue. The most vulnerable dynast is Aurangzeb, who has already ceded a road to a more kindly Muslim who specialized in rocket science. The great Akbar also narrowly survived being displaced by Maharana Pratap. However, the threat of a purge has been mostly directed at the Mughal rulers. Mughal courtiers were never really in the line of fire. T.C.A. Raghavan may have just opened up that possibility by drawing attention to a fact that has sat easy on the Hindu conscience. The 'Rahim' of the dohas that are part and parcel of life in north India is Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan (picture), a Mughal noble who is intrinsic to the milieu that now stands condemned.

Condemning Rahim is the exact opposite of what Raghavan sets out to do. By tracing the career and literary exploits of both Abdur Rahim and his father, Bairam Khan, he tries to show how the Timurid dynasty and the nobility that it reared and inspired, negotiated differences in the territory that they adopted as their home. Many know this cultural mingling to have started at the time of Akbar - when he took Rajput wives, promoted Hindu festivals and then formulated his own religion. And that this intermingling waned before the shock attack of Aurangzeb's puritanism brought it virtually to a standstill.

Raghavan hints that this intermingling had started way before Akbar's intervention. One indication is the presence of Hindi verses in Bairam Khan's writings. The Shia noble, who was Humayun's faithful commander and young Akbar's regent, was not alone in such literary venture. Sanskrit and Hindi dialects were already a part of the political milieu, and they jostled with Turkish and Persian as means of communication between the ruler and the ruled. In Mewat, Abdur Rahim's maternal home, where he spent his childhood years, a rich syncretic tradition persisted. Mewat's Muslims were, in fact, regarded as infidels by the conquering Timurids for their beliefs and practices that drew heavily from Hindus.

Bairam Khan, however, is a minor presence in this book. It is clearly Abdur Rahim, who straddled the courts of both Akbar and Jahangir, who is Raghavan's hero. He is barely five when his father is assassinated and 16 when he accompanies Akbar during the latter's lighting expedition to Gujarat in 1572. But his military valour, political acumen and literary skills gave him lasting space in the court and amid the cultural efflorescence of the time. Raghavan traces the flowering of Abdur Rahim's literary genius to the interludes between intense military and political endeavours. The first phase between 1569-75 saw mixed poetry in Persian and Sanskrit on astrology, and then perhaps a collection of verses on Krishna, Radha and the gopis. A relatively mature phase in 1580-84 saw a flurry of poetry in Hindi on the sexual appeal of women. Then a post-1587 phase that marked a milestone in Hindi literature with his use of the Sanskrit "bhed" genre in Hindi barvais. This was followed by a phase after 1593, when he composed erotic and sensuous poetry. With age and maturity, the theme of poetry shifted to mundane life till life's reverses led Abdur Rahim to the wisdom encased in his famous dohas.

Raghavan undertakes an ambitious project in trying to date Abdur Rahim's work because there is little certainty that all the poems attributed to him were actually penned by him. Besides, there are no chronological markers in the works. There is also such a disjunct between Abdur Rahim's conduct as a Muslim noble and what flowed from his pen that Raghavan himself at times seems uncertain about how to read his subject. Was Abdur Rahim's poetry the result of bhakti or just a literary enterprise? With his sensibility why was Abdur Rahim not at the forefront of religious innovations at the court of Akbar? Why did the orthodox Sunnis of the time never see him betraying Islam? Did he then balance his interests in such a way that he could distance himself from them whenever he needed to?

Perhaps this enormous grey area is what lent Abdur Rahim to convenient interpretations during the turbulent years of the early 20th century, when the need to promote the idea of a plural India and to push Hindi as the national language prompted the rediscovery of his poems and his projection as a national icon. Raghavan's exposition on the different ways in which Urdu and Hindi literature, as also the Hindu and the Muslim world, eventually claimed Abdur Rahim is fantastic. After the unexceptional, although critical, reading of Abdur Rahim's life and literary exploits, the last chapter, "Afterlife: Rahiman and Abdur Rahim", and the Epilogue are electrifying.

What Raghavan makes plain is that the story of the discovery of Rahiman, Rahim or Abdur Rahim is also a story of erasure. When cultural groups and nations claimed him, or his father, as their own, they also erased parts of history that were inconvenient to them. Political appropriation of the historical characters diminishes the texture of their life story "with its many facets, tensions and contradictions, which allow us to navigate the distance separating us from them." Raghavan argues that without understanding the characters in full, together with their accomplishments and flaws, and their decisions, taken rightly or wrongly, we miss the point of entry they give us into our own present. Would then Rahim's champions also accept the inconvenient truths of Abdur Rahim, or save the former's dohas while purging the latter from history?