THE ILLUSTRATED MAHABHARATA: A DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO INDIA'S GREATEST EPIC Dorling Kindersley/Random House, Rs 1,999

In his brief Foreword, Bibek Debroy, one of the two contributors to this rich and rather enormous volume - the other being Devdutt Pattanaik - emphasizes its different approach. It cannot be classed among 'retellings' of the epic, which are innumerable and various, for the Mahabharat has meant different things to different societies in different times, but an effort to draw together "all those cultural strands, past and contemporary". These strands are represented visually, and the book is truly impressive in its collection and arrangement of illustrations from paintings, manuscripts, maps, sculptures, carvings, edifices, dance forms and plays. The meticulous care which the team of picture researchers, designers, illustrators and consultants has expended on the task of building the book is matched by the clarity of planning and overall vision behind the production. It is not a 'retelling' in the conventional sense at all; rather, it is, as the title indicates, a 'guide' to the epic.

How does one re-present the Mahabharat? With its layered stories, multiple themes and conflicts that seem relevant in every age, and a mind-boggling cast of characters each with his or her history and unique dilemma, yet set with a kind of inevitability within the larger, ever-expanding narrative, the epic resists simplification. Although Ganesh is supposed to have taken down its shlokas at Vyasa's dictation, the story is also told and retold, heard and heard again. Among the many little 'boxes' and charts that dot the pages, one lists the narrators and their listeners, ranging from Vyasa and Ganesh to Ugrashrava, Parikshit and Janamejaya among others. Peter Brook's retelling, if it can be called that, attempted to understand the workings of dharma, in which process Yudhisthira became the chief vehicle. That was one route to the contemporary sensibility.

But in The Illustrated Mahabharata the focus is on multiplicity. Presented in 18 chapters, the story takes shape through distilled accounts of the actions and passions of characters, often with a biographical chart with timeline attached and a comment in large print pointing to the spiritual, dramatic, narrative or moral colouring of the moment. The full impact of the narrative, however, is conveyed through paintings and images from the oldest temple bas-reliefs or carvings in, say, Angkor Wat, or manuscripts and maps, right down to paintings by Raja Ravi Varma, for example, or Kathakali performances, modern theatre and dance presentations, or traditional folk paintings, and other, startlingly beautiful, illustrations from outside India. The only pages without illustrations are those that contain the Gita's shlokas. The overall effect is dazzling. It turns The Illustrated Mahabharata into a memorable record of artistic responses - as though a thousand brilliant imaginations have been lit up by one incomparable text. Just as the epic itself gives the impression of being not one voice but many, the responses it evokes are multi-voiced, each of which gives back its own understanding of the tale.

The design also enhances the effect of layered resonance. Inset stories, with illustrations from the West, occasionally bring out similarities, like that between Medea and King Shantanu's first wife, Ganga, both of whom killed their children. But Medea killed them as an act of revenge against Jason, her husband, the note points out, while Ganga did it to free the children - fallen demigods - of a curse.

The retelling of the 18 chapters is preceded by an introduction that lays out the conceptual premises of the epic, discussing the scriptures, deities, ideas of history and time, the Hindu cosmography and so on. Certain practices still prevalent, such as yagnas, are shown in their modern forms, thus connecting the ancient with the contemporary. The most pertinent of these presentations is that of varna, which, the text points out, is not quite the same as caste. The section on Ekalavya, for instance, with its photograph of a tribal man aiming his bow without using his right thumb, brings together many of the concerns of this volume. Ekalavya's devotion to his invisible guru, Drona, and the sacrifice of his right thumb are related not only to living issues of caste and loyalty, but also to the ways in which a story is received. Drona and Arjuna, heroes to most, are villains to the Bheel tribe, who refuse to use their right thumb out of respect for Ekalavya.

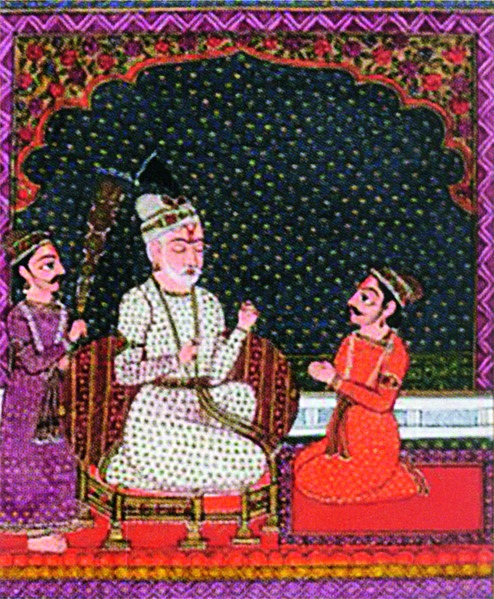

The illustrations can tell the story by themselves. Suta Sanjay, charioteer and storyteller by virtue of his varna, reports to Dhritarashtra the progress of the war (top). The Razmnama, the epic translated into Persian and intended by Akbar to bring Hindus and Muslims closer, is striking for its illustrations. Brilliantly attired, Pandava and Kaurava armies assemble before the battle (second from top). In a 17th-century watercolour from Karnataka, Draupadi watches as Bhima battles Kichaka (third from top). Depicted in the Jaipur style, Bhima carries his mother and four brothers to safety from their burning lac house (above). Bhima's size evokes his future offspring, Ghatotkacha, who will crush his father's enemies with his dying body. The five Pandavas line up as Wayang puppets from Java (second to last), and Krishna protects Draupadi from shame (below) in a Madhubani painting. Dharmaraj or Yama, whose judgment - and presence through Vidura and Yudhisthira - dictate the progress of the epic, sits in state (below, last) in his temple in Mysore.