A joke is a joke is a joke, the wise one could have said. But the Supreme Court did not laugh off a petition about humour as many thought it would. The petitioner, advocate Harvinder Chowdhury, had sought a ban on Santa Banta jokes, saying that they ridiculed the Sikh community, of which she was a part.

In her public interest litigation (PIL), Chowdhury said these jokes — featuring two characters, Santa Singh and Banta Singh — violated the Sikh community’s fundamental right to life and dignity guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution. The article states, “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.”

Though the court had its reservations, it agreed to hear the petition. What prompted it to do so?

“I believe that the court has accepted this plea only to sensitise people. People should not crack ethnic jokes but that does not mean you have to ban Santa Banta. We all have freedom of speech and cracking jokes is not prohibited by any law — so this case is meant only for sensitising people,” senior Supreme Court advocate Prashant Bhushan believes.

The case also brings up another issue — that of freedom of speech, which has often been debated by the apex court. In May, the Supreme Court had decided to examine a plea that sought quashing “hate speech” sections — 153, 153A, 153B, 295A, 298 and 505 — as unconstitutional.

The court had earlier struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000, that allowed governments to prosecute citizens for “objectionable” Internet posts. The petition came up in the court following the arrest of two girls in Maharashtra by the Thane police in November 2012 over a Facebook post. The comments related to a shutdown in Mumbai for the funeral of Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray. The arrests triggered widespread outrage.

The Internet has been the platform for many posts and jokes which somebody or the other may find offensive. There was were loud protests in 2012 when Jadavpur University professor Ambikesh Mahapatra was arrested for forwarding caricatures of West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee on the Internet, and when activist Aseem Trivedi was charged by the Mumbai police with sedition for drawing cartoons lampooning Parliament and the Constitution.

Clearly, one man’s humour is another man’s poison. In this case, the petition states that the jokes violate a fundamental right. But legal experts believe that banning the jokes would actually flout constitutional rights.

“To ban a concept or idea will definitely constitute an infringement on one’s fundamental right,” senior Supreme Court advocate Sanjay Sen states.

The Supreme Court, some believe, may take the opportunity to stress the need for freedom of speech as guaranteed by the Constitution of India. Sen observes that the apex court has had a long history of safeguarding the right to freedom of speech.

He cites the example of a 1950 case relating to the journal Cross Roads edited by Romesh Thapar. This was one of the first cases that was decided by the Supreme Court under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, which guarantees the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression. “The Supreme Court held that freedom of speech and expression includes the freedom to propagate ideas,” Sen says.

Senior Supreme Court advocate Harish Salve believes that the PIL underlines two aspects of life that have gone “horribly” wrong. “One is the craving for publicity — and the perception that everyone with a point of view should move the court to impose his view of life upon the system,” he says.

“The second is that we have lost the capacity to laugh at ourselves. In every community, there is humour based on characteristics, which is taken in the spirit of mirth — not as a serious attack on the values of a community. The Irish jokes, the jokes on the Polish, on Jews — the list is endless.”

Sikhs, he believes, have enjoyed Santa Banta jokes as much as others. “If someone lacks a sense of humour, he can stay away from them. To suggest that it is violative of the norms of free speech is nonsense.”

Indeed, there have been jokes on all communities. Bengalis, for instance, are often lampooned, as are Marwaris, Gujaratis and so on. Jokes against professionals are equally popular. But these jokes, Sen argues, have to be just laughed off.

“Globally there are more lawyer jokes doing the rounds than the Santa Banta variety. The world has accepted Polish jokes for over several decades,” Sen points out.

Agrees Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya, a senior advocate at the Calcutta High Court. “I feel people should be tolerant enough to take harmless jokes in their stride. There are jokes on so many communities. We have Nonte Fonte, Handa Bhonda, Gopal Bhand and so on,” he says referring to some popular Bengali jokesters and targets. “You have to judge the intention of the material and see if the content is harmless.”

There are some who argue that Santa and Banta in any case are not specific to the Sikh religion. “Santa Banta are an integral part of our life and provide us with smiles and laughter in this stressful life,” says Jeevan Deep Singh Ghai, founder and CEO of SantaBanta.com. “Santa and Banta at SantaBanta.com represent secular India, as does the logo of our company. And we never use the word Singh alongside Santa and Banta.”

“It is a shame that the people of India of do not value their right to freedom of speech — it is a glory that very few countries give to people. So let’s respect it,” Bhattacharya says.

But it cannot be denied that cruel jokes can also hurt someone’s sensibilities. And since there are no set definitions for offensive humour, perhaps it is the responsibility of every citizen to know where to draw the line.

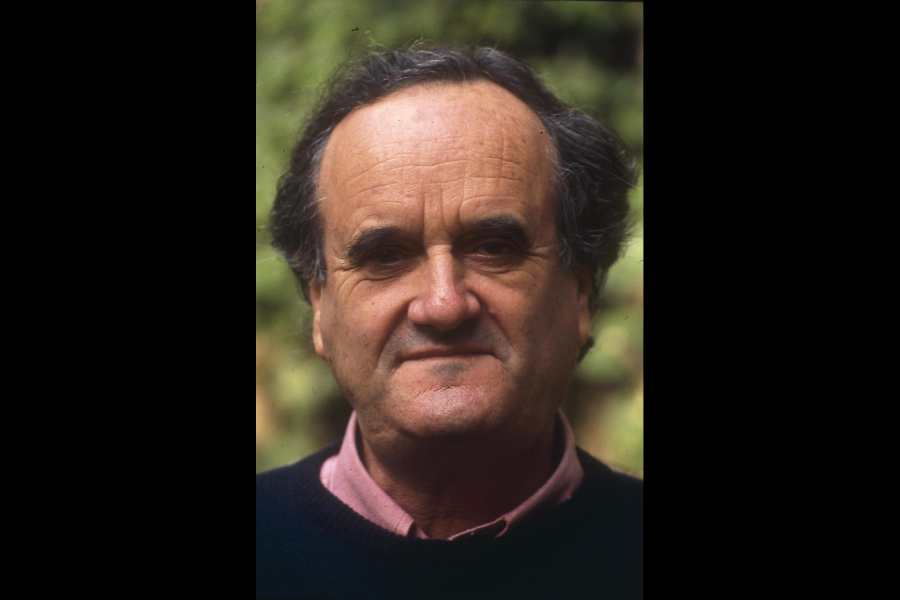

“Freedom of expression is an incomplete value unless it is used honourably,” Fali S. Nariman sums up, quoting a speech delivered by the Aga Khan at a symposium in Portugal in 2006. “The obligations of citizenship in any society should include a commitment to informed and responsible expression.”