|

| |

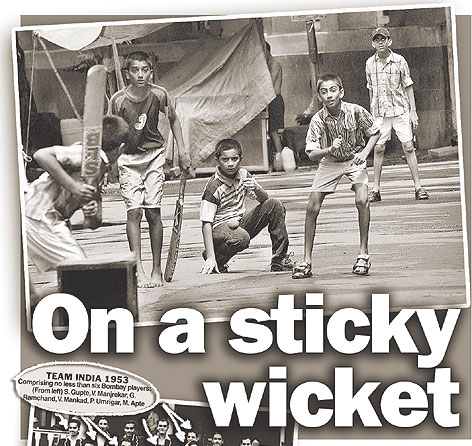

| ON THE STREETS: Children play cricket in a back alley of Mumbai Photo: AFP Team India 1953 Comprising no less than six Bombay players: (From left) S. Gupte, V. Manjrekar, G. Ramchand, V. Mankad, P. Umrigar, M. Apte Team india 2004 With only one regular Mumbaikar Test player: Sachin Tendulkar, now out with an injury Photo: Reuters |

For a city that has always been an assembly-line producer of India?s finest cricketers, the unthinkable happened on Thursday. Few know that when Sachin Tendulkar missed playing the ongoing India-Australia Test in Chennai, the batting maestro unwittingly broke a record that was Mumbai?s proud badge of honour. Tendulkar?s continued absence ? he had missed the earlier Bangalore Test too ? means that for the first time in India?s 72-year-old Test cricket history, nobody from Mumbai was playing in the national XI for two consecutive games.

Ever since cricket grew roots in India in the 19th century, the western megapolis has always been acknowledged as the nation?s cricket capital, producing great batsmen such as Vijay Merchant, Vijay Manjrekar, Sunil Gavaskar, Sachin Tendulkar and many more. Be it the 1971 Oval Test (six Bombaywallahs) or the 1980-81 famous Melbourne triumph (four of them), the Bombay boys were ubiquitous and so were their surnames ending with the letters, kar. Of the 248 who have played Test cricket for India, 65 of them ? or one out of every four ? are from Mumbai.

Only once, way back in 1966-67, Mumbai was missing from the national XI. That was against the West Indies in Eden Gardens. ?I think Wadekar fell ill at the last moment. So I replaced him,? recalls former Test batsman Abbas Ali Baig. But in the next Test at Madras, now Chennai, the top three batting slots were taken up by the Bombay boys: Dilip Sardesai, Farokh Engineer and Ajit Wadekar.

For many years, when Mumbai was Bombay, it was believed that its supply of world-class batsmen would never cease. Now, the tap has run dry. Since Sanjay Manjrekar and Tendulkar made their entry in world cricket in the late Eighties and Vinod Kambli in the early Nineties, most Mumbai internationals ? Wasim Jaffer, Ajit Agarkar (now among the reserves), Nilesh Kulkarni, Paras Mhambrey, Abey Kuruvilla and Sairaj Bahutule ? have merely been sideshows. Mumbai has not produced a fresh Test regular in the past 10 years. In any case, most of those who have played Test cricket are bowlers/all-rounders and not batsmen, the city?s core competence.

Trophies don?t tell the real story. Despite being the present Ranji Trophy champions, former Test cricketers and Mumbai Cricket Association (MCA) officials admit cricket in the city is in decline. ?It?s a critical situation,? says Milind Rege, ex-Mumbai player and now administrator. Nobody is close to becoming the Next Big Guy ? a potential Tendulkar, or even a Dilip Vengsarkar ? that the nation expects from a city that plays host to India?s two great, abiding passions: films and cricket.

For many Mumbaikars, the situation is no less than a crisis. Old-timers wonder if the city?s decline as a domestic cricket superpower is located in the larger social changes that have swept the Maharashtra capital over the years. Environment writer Darryl D?Monte thinks the phenomenon may have something to do with the city?s declining open space ? Mumbai has the highest density of population at 0.03 acre space per 1,000 people. It is a city where now over five million live on the streets and 73 per cent live in single-room homes.

And, editor Nikhil Wagle, who earlier brought out the Marathi cricket magazine, Shatkar (Sixer), believes that Mumbai has lost the appetite for hard work. ?Cricket was a passion then. Now it is big business. You see 100 nets in Shivaji Park but where is the seriousness?? he asks.

Bombay was always India?s fast-buck city, famous for its underworld, films and commerce. But, in post-Harshad Mehta Mumbai, as Rege sums up, ?the get-rich-quick mentality has filtered down even in sports?.

Nothing, perhaps, encapsulates the changed face of Mumbai cricket more dramatically than the vanishing of the Parsis. In his book, A Corner of a Foreign Field, social historian Ramachandra Guha writes that the first Indians to play cricket were the Parsis of Bombay. The Parsis not only played a crucial role in shaping Bombay?s economic destiny but also contributed immensely to its willow game. Players like Rusi Modi, Polly Umrigar and Farokh Engineer played with merit for Bombay and India.

No longer. Zubin Bharucha was the last Parsi to have played for Bombay in 1994-95. And, not surprisingly, has since migrated to the USA. The latest census figures show that the city?s Parsis are decreasing in number. But former India batsman Umrigar refuses to buy that as a reason. ?The new boys are not prepared to work hard,? he says.

It?s a common allegation by old-timers who stoutly believe that they were far more dedicated to the game than the new boys. In his book on Bombay cricket, Guts and Glory, journalist Sandeep Bamzai recounts how Ranji player Sudhakar Adhikari got married in the morning, turned up to play a game and attended his own reception the same evening. And, Rege could not be present at close friend Gavaskar?s wedding for he was playing a Ranji game in Junagadh.

Such work ethic was routine in the Bombay maidans till the Eighties and earlier. For many middle-class Maharashtrian boys, says Sanjay Manjrekar in Bamzai?s book, cricket was one of the few routes to both izzat (respect) and shohrat (fame). That has changed in post-liberalised India where avenues for easy fame and money abound. Manjrekar himself retired in his early 30s swapping the bat for the microphone. Paceman Salil Ankola quit in his prime opting for the greasepaint and Kambli continues to dabble in television shows, cinema, modelling; never really concentrating single-mindedly on his cricket. It is no coincidence that Mumbai has not produced a single great cricketer in the post-satellite television era beginning in the early Nineties.

Former Indian captain Ajit Wadekar laments the loss of pride and passion when playing for Mumbai. He tells you a story. Bombay lost to Maharashtra by one run in a nail-biting 1964 Ranji game. ?Fast bowler Umesh Kulkarni was the last player to be dismissed. He just sat on the pitch and wept. We had that kind of feeling,? he says.

Competition was intense even in local club cricket. ?After his first failure for Bombay, even Gavaskar had to wait for several years before he got a second chance,? says Rege. Now with decreasing competition and increasing club tournaments, ?players don?t value their wickets anymore,? feels Wadekar. Then the HD Kanga league and the inter-office Times Shield were played by top international cricketers and watched by thousands. Now national cricketers tour the year round and the local league has been de-glamorised and de-valued. ?All top state-level players go to play in the lucrative Scotland and Ireland league,? says former Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) president Raj Singh Dungarpur.

Dungarpur cites the loss of corporate support ? SunGrace Mafatlal and several other business houses dismantled their city cricket teams some time ago ? and a profusion of one-day cricket as some of the reasons for the absence of technically perfect batsmen that Mumbai once specialised in producing. ?These days even young teenagers play one-day cricket. How will they learn the grammar of batting?? His feelings are echoed by Tendulkar?s coach Ramakant Achrekar who feels that the earlier generation ?played more correctly?. And Wadekar laments the new scenario ?where there are more commercial coaching centres than coaches?.

But others, such as former Test cricketer and national coach Madan Lal feel that these problems are not specific to Mumbai. ?Commercialisation is everywhere,? he says. He believes that earlier, cricket in India was limited to a few city centres, it has now spread to different parts of the country. He says, ?Now we have Test cricketers coming even from Orissa. Who would have believed that in the Seventies?? In other words, others states have closed the gap.

In that sense, the decline of Mumbai as a domestic cricket superpower is also linked to the rise of the others ? first, north India under Delhi?s Bishen Singh Bedi in the Seventies and later states like Karnataka in the Nineties. And to India?s 1983 World Cup triumph which created a nationwide euphoria and contributed to the mofussilisation of the game.

That apart, Mumbai has also lost out in cricket administration. The BCCI centre of power has shifted eastward. So has the captaincy. Consequently, none of its fringe players get a look-in. ?See, if Ravi Shastri had not retired early and had become India captain, I know I would have got my break much earlier,? says a former Test cricketer who retired recently.

About four years ago, Mumbai Cricket Association saw the writing on the wall and formed a Cricket Improvement Committee. Top cricketers such as Vengsarkar, Lalchand Rajput, Sandeep Patil and senior coaches such as Vasu Paranjpe got involved in talent spotting and coaching.

But Rege is still not happy. Forget Tendulkar, Mumbai is unable to find quality replacement for Kambli and Bahutule, men at the centre of their successful Ranji campaigns in the past two years. ?The newcomers get the best of facilities and coaching. But I still cannot understand why a player cannot bat the whole day,? he wonders.

The truth is that the larger socio-economic climate, which once made cricket the first choice of thousands of Mumbai youths, has changed dramatically in the past decade. These days, it is more a thousand parents? obsession to make the next Tendulkar out of their sons which keeps city cricket thriving in the form of commercial coaching.

Perhaps, Mumbai has to readjust to the changed socio-economic conditions. Wagle predicts that the next generation of cricketers will come from the suburbs and not from the main city. ?They are more hungry for success. They are willing to work hard,? he says. Says a Test cricketer: ?The focus of attention should shift to improving grounds and infrastructure in the suburbs because that?s where many young players are coming from.?

And, perhaps, Mumbai should stop looking for a Merchant, a Gavaskar or a Tendulkar. These batsmen were creations of another age. Now when 20-over internationals are likely to be the game?s next big draw, both batsmanship and bowling are being constantly redefined. As in other aspects of its existence ? infrastructure, politics and commerce ? Mumbai will need to reinvent its philosophy of cricket.