It is the best of times, it is the worst of times in Nepal, to borrow the words of Charles Dickens. The youth of that country have risen to overthrow a government that was mired in accusations of corruption but over 30 people have lost their lives, more than 1,300 have been injured, and there have been significant losses in terms of built heritage. Interpretations of Nepal’s current crisis have been weighed down by such familiar frameworks as geopolitics, history and sociology. Parallels have rightly been drawn with last year’s protest against the Sheikh Hasina regime in Bangladesh and the Sri Lankan Aragalaya in 2022. But there is reason to make a somewhat ambitious — even audacious — claim: the events unfolding in Kathmandu can be read through literature too.

What the world is watching in Nepal is a farce being played out as tragedy. Like Napoleon from Animal Farm banning the anthem, “Beasts of England”, in the hope that he could suppress dissent, the government in Nepal banned social media in the hope of keeping a lid on public dissatisfaction. Ministers defended their privileges while lecturing about austerity, just as Falstaff in Henry IV glorified honour while being corrupt and self-indulgent. Indeed, Nepal’s suited generals deploying force against tattooed teenagers with slogans on their T-shirts had a truly Shakespearean ring to it — for the bard captured the sign of the times in King Lear when he wrote, “Through tattered clothes small vices do appear; /Robes and furred gowns hide all.” If the farce is the result of an absurd disconnect between the rulers and the ruled, the tragedy lies in what it reveals: entrenched social inequality, a culture of corruption, the wastage of a demographic dividend, the repetition of cycles of violence and chaos that Nepal’s history knows all too well. The monarchy fell, the republic promised rebirth, yet the institutions born of that change are faltering. Thomas Hardy’s bleak words, “Happiness was but the occasional episode in a general drama of pain”, seem to capture Nepal’s tryst with political destiny with precision.

Shakespeare, of course, supplies the richest parallels. In Hamlet, when the young prince whispers, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”, he might as well have been speaking of Kathmandu. The rot in Nepal is not murder in Elsinore, but the decay of a political class addicted to self-preservation while being blind to the legitimate needs of a restless generation. And then there is Macbeth. The prophecy that Birnam Wood would march to Dunsinane seemed laughable — until the soldiers advanced

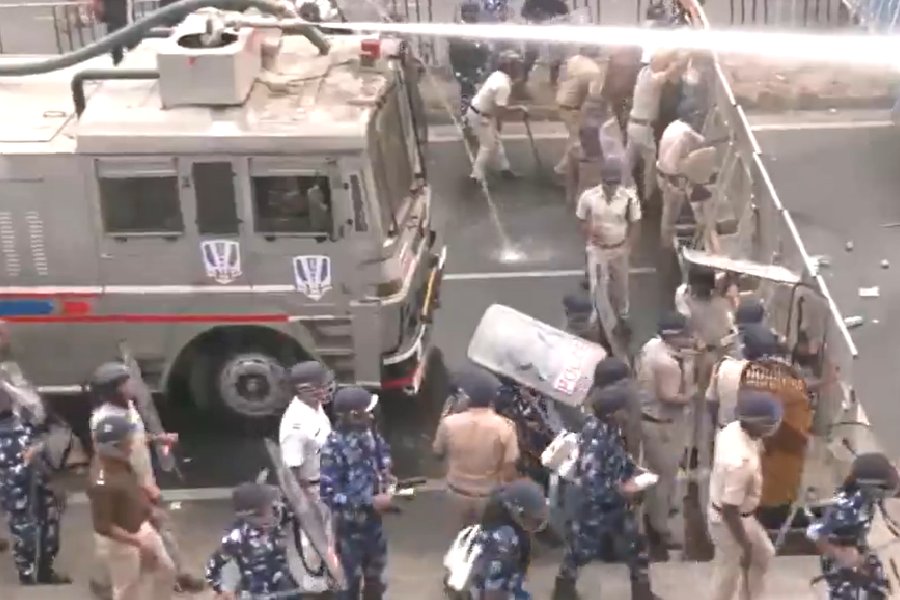

disguised in branches. To Nepal’s rulers too, Gen Z long seemed passive, self-obsessed, and apolitical. Suddenly, though, the proverbial forest stirred. Ordinary students, freelancers, and unemployed youths became an advancing army, armed not with branches, but with hashtags, songs and slogans.

The Kathmandu protests belong to a lineage of sudden collective uprisings, moments when a silent crowd acquires the rhythm of a storm, reminiscent of the storming of the Bastille in A Tale of Two Cities or Émile Zola’s miners swelling in rage against

an authoritarian order. “What is the city but the people?” asks Shakespeare in Coriolanus. Kathmandu’s streets are answering that question. The forest is moving. The tyrants in the castle should tremble — in Nepal and elsewhere.