The Central biotech regulator, the Genetic Engineering Approval Committee has recommended the commercial use of genetically modified or GM mustard after much deliberation and several rounds of field trials. It is believed that GM mustard would be beneficial for agricultural growth in the country and would end India's dependence on other countries for the import of edible oil. At present, India imports edible oil worth 11 million dollars, nearly one-third of what the country gains by exporting agricultural commodities. After three years of deliberation, the biotech regulator has agreed to its limited use for commercial purposes from the coming rabi season. GM mustard seeds have been developed in an Indian laboratory and by a group of scientists from the Delhi University, which makes it a truly desi product. The project was funded by two national organizations, the National Dairy Development Board (the largest producer and supplier of the Dhara brand of oil) and the government's department of biotechnology.

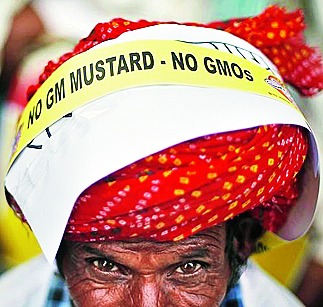

The idea behind this new project was to make the country self-reliant in mustard oil production. Countries like the United States of America, Brazil, Argentina, China and others are using GM seeds for the production of maize, soya bean, cotton, canola, papaya and paddy. In the US, 72.9 million hectares of land are being used for the production of GM crops. Brazil is using roughly 49 million hectares of land. At present, India is trying out only with BT cotton in 10.8 million hectares. Because of stiff opposition from activists, the introduction of BT brinjal was stalled in 2010. Since 2013, GM mustard has been opposed by activists on the ground that the new seeds can pose serious scientific and technical challenges to farmers, besides causing environmental degradation and health hazards. Activists allege that no attempt has been made to share field trial data with the farmers. The Supreme Court will have to take a call on this contentious issue in the coming months. Before the new seeds cause another spate of farmers' suicides something needs to be done.

The GM mustard seeds have been opposed on other counts too. Aruna Rodrigues, an activist, argued that the Centre's preliminary clearance to GM mustard, named Dhara Mustard Hybrid-11 (DMH-11), contravenes a 2013 report by a Supreme Court-appointed technical expert committee. This committee had said, among other things, that herbicide-tolerant crops ought not to be permitted in India. One of the genes in DMH-11, developed by researchers, contains 'bar' that makes it herbicide tolerant. This makes plants resistant to a class of insecticide containing the chemical, glufosinate. After the disastrous consequences of using BT cotton seeds in Vidarbha, Maharashtra and other parts of the country, questions are being raised about the efficacy of GM mustard. Initially, in the 1990s, BT cotton seeds were imported in a clandestine manner bypassing all checks and control by government agencies. The farmers were told by the agents of the wholesale dealers that BT cotton output would ensure a quantum jump in the cotton production. The cost of production of the new crop was three to four times higher, farmers had to borrow money at a high rate of interest from moneylenders. After sowing, they waited, only to find insecticides destroying the cotton fields. The disaster led to a large number of farmers' suicides. In the early 1990s, nearly one thousand farmers committed suicide by consuming pesticide in Maharashtra alone.

Why did the farmers use new genetically modified BT cotton seeds of the multinational company called Monsanto in the 1990s? One answer to this question is that they took the risk because they had gained some kind of confidence in using new seeds after the successful introduction of high yielding varieties and various other inputs during the Green Revolution. Moreover, different types of HYV seeds were also introduced by the Indian agricultural research institutes with which farmers had no problems. However, the simple narratives of risk and trust fell apart when BT cotton seeds were introduced: the new seeds gave farmers a nightmare and within a short time cotton cultivation with the new seeds was abandoned in many parts of the country.

Other problems aggravated the crises in Maharashtra, like adulterated and spurious inputs, lopsided flow of institutional credits and indebtedness, the mismatch between the expected and actual yield of cotton, the breakdown of the joint family system, ecological factors like soil degradation owing to the excessive use of chemicals and fertilizers. The factors worked in a complicated way in leading to suicides.

However, the Green Revolution made scientific knowledge popular among farmers. Agricultural innovations with new HYV seeds has changed the contours of local knowledge about farming in the last five decades. Science made inroads into the world of local knowledge in remote areas in agriculturally backward states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. The triumph of science over traditional techniques of cultivation helped farmers gain trust in new discoveries, especially in seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. Constant interaction between agricultural scientists and farmers made it easier to spread Green Revolution technology. Agricultural scientists made it a point to ensure that farmers became important stakeholders in spreading this in rural areas; frequent field trials by agricultural scientists helped bridge the gap between scientists and farmers.

The disaster in Vidarbha has broken the trust that farmers gained after the Green Revolution and it has allowed local knowledge to regain lost ground. Indian agriculture would hardly benefit if scientific knowledge does not percolate down to the villages. Science has an important role to play in augmenting agricultural production and from this point of view new seeds or GM crops can fulfil two primary objectives: first, they can increase food production and second, they can make India self-sufficient in producing edible oil and cotton. In order to fulfil these two broader objectives, science has to reach those who till the land. But this is not happening with GM seeds; farmers are being ignored by the State and by scientists.

Before introducing GM mustard, it would be necessary to involve farmers, the main stakeholders, in this new venture. In many parts of India, farmers are well-organized; they are controlled either by unions or by their caste associations. Sometimes they join hands without taking support from unions or caste associations as is the case in the present farmers' agitation in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. In West Bengal, the Left Front paid a heavy price for not consulting peasants before land acquisition in Singur and Nandigram. A spontaneous agrarian struggle forced the state government to abandon land acquisition. On a contentious issue like the introduction of GM crops, farmers should get an opportunity to express their opinion. After all they are the main stakeholders, they must be heard.