As Independence approached, our cook asked me, then a boy of nine, who India’s new king would be. The glazed eyes with which he listened to my laboured explanation about president and prime minister would have vanished, I am sure, if he had seen Narendra Modi crowned with a gilt tiara by the head priest of a 10th-century Ayodhya temple. Or brandishing a five-foot golden sceptre that evoked the magic of Chola princes who ruled in the third century BC and lorded it over Southeast Asia in the 11th.

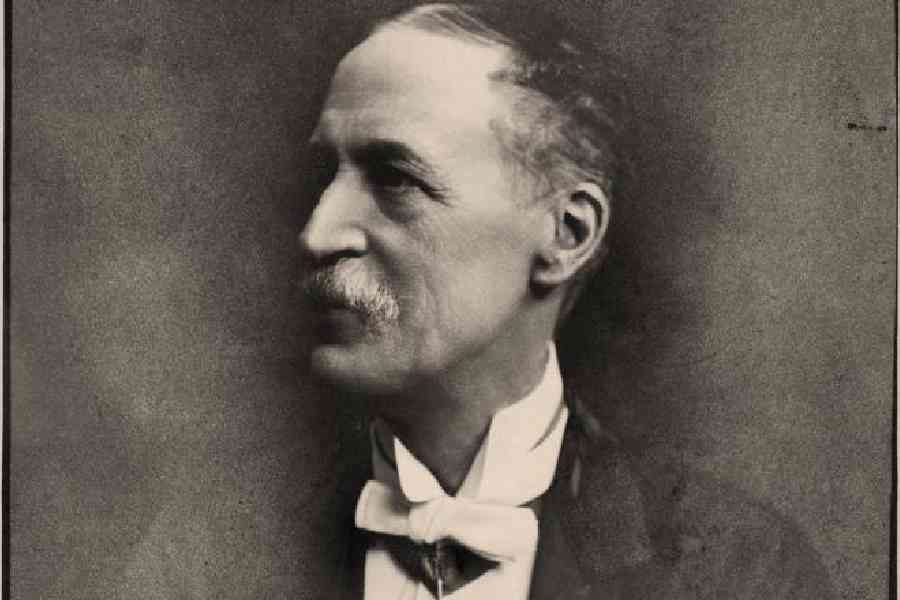

One reason why Indians were denied such illumination in 1947 may have been the bhadralok dominance of all aspects of life. Of course, C.J. Fuller, emeritus professor of anthropology at the London School of Economics, doesn’t actually say so in his meticulously researched Anthropologist and Imperialist: H.H. Risley & British India 1873-1911. His claim that Herbert Hope Risley of the Indian Civil Service was much taken by “the Bengali Hindu, high-caste, educated, urban middle class, whose members supplied the vast majority” of educated professionals “as well as most subordinate government officials and clerks” may even reflect to some extent Fuller’s own absorption in the phenomenon. But as long as Jawaharlal Nehru’s liberal secularism shaped the bhadralok outlook, it kept at bay religious dogma, militancy and extravagant but obscurantist ritual. Fuller says this restraint also owed something to the moderate nationalism of men like Surendranath Banerjea and Ashutosh Mookerjee (Shyama Prasad and the Jana Sangh lay in the future) although Risley “knew relatively little about their personal beliefs and next to nothing about those of the extremists he probably never even met, such as Aurobindo Ghosh.”

Nor may he have been familiar with the Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha, previously the Sarvadeshak Hindu Sabha, established in 1915. However, sending Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, later the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s first president, to Calcutta Medical College to qualify as a licentiate doctor was a political decision that should not have escaped official attention. Risley did recognise the slant that Shivaji’s exploits against the Mughals lent to the nationalist cause in Maharashtra but, on the whole, the powerful bhadralok ethic — far removed from the mumbo-jumbo of today’s catch-as-catch-can world — may have spared India’s alien rulers exposure to many aspects of the national psyche that a thorough examination of the evolution from primitivism to sophistication would have revealed.

Fuller’s earlier work, Ethnography and Racial Theory in the British Raj: The Anthropological Work of H.H. Risley, affirmed that the “declared purpose” of anthropology “was always both ‘scientific’ and ‘administrative’: to contribute to modern, European scientific knowledge and also to strengthen and improve British rule.” That purpose may have succeeded in ensuring that Risley and his colleagues continue to influence many later anthropologists and scholars who “would certainly condemn their imperialist views and have probably never read anything they wrote.” But even if the scholarship of part-time or even full-time anthropologists like Risley, Henry Maine, D.C. Ibbetson, Alfred C. Lyall and others was not dismissed as an apologia for colonialism, as in the case of some white scholars in Africa, the marriage of scholarship and imperialism does not appear to have produced many new insights into the art of governance.

Knowledge is power, and anthropology could have been a key instrument in the task of studying and understanding India. Indigenous pioneers like the virtually forgotten Biraja Sankar Guha, the first director of the Anthropological Survey of India, who was tragically killed in the 1961 Ghatsila predecessor of the Odisha railway disaster, could have played a crucial part in shaping policy on matters like separate electorates, ‘criminal’ tribes, Hindu and Muslim personal law and other issues that give administration in India its unique human appeal. Anthropologists should have become the power behind the throne by authoring variants of Verrier Elwin’s A Philosophy for NEFA and formulating and implementing the British raj’s equivalent of France’s mission civilisatrice. Constructive use of anthropology might have spared India decades of ethnic conflict in the Northeast as well as the siege mentality that is said to grip Indian Muslims. Rudyard Kipling’s ‘white man’s burden’ need not have been confined to Americans in the Philippines.

If that didn’t happen, it may have been for a number of reasons. Guha’s specialisation — classifying Indians racially — fell out of favour with scholars committed to universal humanism. What has been called the ‘biologising of society’ evoked too many uncomfortable memories for Europeans. Jaipal Singh Munda’s adolescent eldest son would not have thought it necessary to arm himself with a knife (as he told friends and relatives) if his father’s lament about “the new comers who have driven away my people [Adivasis] from the Indus Valley to the jungle fastness …” had been taken seriously. The one-time Constituent Assembly member and captain of India’s victorious 1928 Olympic hockey team died a disappointed man in 1970.

Imperial considerations thwarted some causes. Communal fears suppressed others. Edward Said brought a new focus to bear on colonial perceptions. The ‘end of anthropology’ was once discussed as fervently as the end of history. Some might have found Ashok Mitra’s preferred communist view of society more relevant than the bhadralok version he spurned. Others might altogether have denied the latter. Mamata Banerjee, then still an Opposition firebrand, ended a thundering tirade to Calcutta’s remaining captains of business and industry with the ringing declamation that wearing a dhoti alone didn’t make a bhadralok.

Just as Risley also authored The Gazetteer of Sikhim, Guha’s diverse studies ranged from the tribes of the northwestern Himalayas to Burmese Nagas, East Pakistan refugees to the Abor dormitory system. Looking back some 70 years later, I wonder if his expansive flat in Calcutta’s Hungerford Street where teenagers like me were hospitably welcomed in the 1950s was in reality an informal laboratory. After all, Guha was an eminent physical anthropologist who had also pioneered the popularisation of his scientific ideas in Bengali. He must have found it in some way rewarding to keep open house on a regular basis for the Bengal Youth Organisation as, I think, our totally apolitical club was called. Not that I was ever aware of any serious purpose in those agreeable evenings.

We know that the colonial authorities kept a close watch on terrorists and communists. I wonder now if Hindu militancy aroused similar interest. When the RSS was set up in 1925, did any imperialist anthropologist wonder about the true nature of a nationalist organisation that called for a ‘Hindu rashtra’ but did not support the Quit India movement and instead endorsed Britain’s war effort and the Zionist occupation of Palestinian land? The Bombay government of the time dismissed the RSS as “not a problem”. Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana’s Unionist Party regime of Muslim, Sikh and Hindu landlords in Punjab banned it for precisely four days in January 1947.

True, the political Right did not challenge colonial rule. But after no fewer than four postings in Midnapore, a hotbed of disaffection in those days, to say nothing of three years as a legislator, Risley could not have been unaware of discordant voices. The scholar’s professed political neutrality should have demanded as stringent an investigation of the RSS’s early links with the Anushilan Samiti and Kranti Dal as of the possible impact of the rhetoric of Hedgewar and Madhav Sadashivrao Golwalkar who took over in 1940. Did anyone not notice the smouldering bedrock of majority grievance that some might trace back to the Sanyasi Rebellion of 1771 and consider the likelihood that it might one day be ignited? Whether or not that day has dawned, the ferment may at last have answered our cook’s artless question.