It is often said that public memory is short. Though there is some truth in the saying, there are those rare moments that remain etched in the collective consciousness of a people. The Emergency is one such episode that continues to occupy a prominent space in the public discourse of India. Almost four decades have passed since the Emergency, but time has not diminished the intensity of the debates and discussions related to it. On the contrary, the Emergency has emerged as an important area of study for those interested in the history of modern India.

Quite expectedly, a slew of books on the Emergency have been penned over the years. The Communist Party of India and the Indian Emergency by David Lockwood is a recent addition to that burgeoning genre. Lockwood has chosen a rather novel way of exploring the period. His book, as the title suggests, is primarily concerned with the Communist Party of India and its response to the Emergency. The principal players of that time - Indira Gandhi, her son, Sanjay Gandhi, the Congress, Jayaprakash Narayan and the Janata Party - have all been looked at from the perspective of the CPI. The CPI, it ought to be remembered, was the only prominent party to extend support to the Congress during the Emergency. It is important to learn why the CPI, in spite of popular criticism, decided to back the prime minister, Indira Gandhi, and her party, the Congress.

Lockwood has begun by delineating the CPI's opinions about the Congress since Independence. This may come as a bit of a surprise to some readers, but there had always been a strong lobby within the communist party that advocated close cooperation with the Congress. Many early communist leaders like P.C. Joshi were impressed with Jawaharlal Nehru's leadership. Joshi went to the extent of calling Congress, "the greatest national organisation of the country". The split within the CPI in 1964 strengthened those voices within the party that viewed the Congress favourably. The more radical elements of the party, those who considered Congress "the chief party of counter-revolution", left to form the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

Thereafter, the CPI (whatever remained of it) needed little evidence to convince itself of the fact that the Congress could be used as a bulwark against anti-communist forces. Indira Gandhi's bank nationalization move gave the communists more reason to believe that with her at the helm of the government, they could bring about radical changes, including land reform in the agricultural sector - which had been the pet agenda of the CPI for long.

Another factor that brought the CPI closer to Indira Gandhi was her proximity to the Soviet bloc. The year 1971 was a watershed moment in this regard. The hostile role of the United States of America during the Bangladesh Liberation War made Indira Gandhi tweak India's foreign policy. Though the country continued to be a part of the non-aligned camp, there remained no doubt that India was now a firm friend of the Soviet Union. Naturally, the move to embrace the latter could not but have been appreciated by the communists.

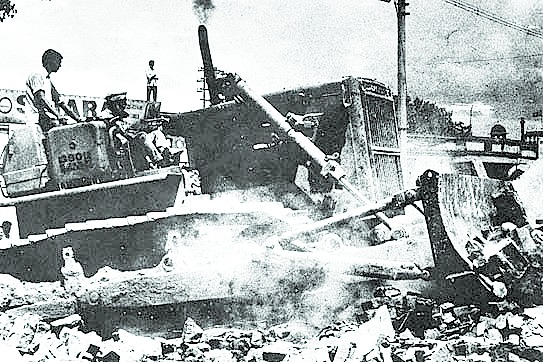

So, by 1975, the year Emergency was promulgated, the CPI had inched ever closer to the Congress. This was also the time when the anti-Congress movement under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan was peaking. Students and workers were at the forefront of this campaign. The strike by railway workers in 1974 is a case in point. George Fernandes, the president of the All India Railwaymen's Federation, enthusiastically linked the strike to the campaign for the removal of the Indira Gandhi government. Soon after, L.N. Mishra, the Union minister of railways, was assassinated in January 1975. The CPI, it needs to be mentioned here, was not comfortable with Jayaprakash Narayan's campaign. The party considered the JP Movement, as the latter was popularly known, as a movement of the reactionary and fascists forces to oust Indira Gandhi from power. So, when Indira Gandhi imposed Emergency in June 1975, the CPI came out in her support in no time. Apart from the usual argument of thwarting right-wing forces, the CPI also advanced the 20-Point Programme undertaken by the Centre to justify its decision to support Indira Gandhi. The 20-Point Programme included the distribution of surplus land and measures to keep prices down.

That is all so well. But what made the CPI continue its support for the Emergency? The brutal repression of dissenting voices must have not escaped the notice of the CPI leaders. The CPI did not withdraw its support to the Emergency even when Sanjay Gandhi and his coterie started exercising extra-constitutional authority. Unfortunately, the author fails to provide any plausible explanation for this. Lockwood has harped on the CPI's policy of "unity and struggle", adopted in relation to the Congress, but that is just about it. The "unity and struggle" was a tactical line, by which the CPI wanted to underline that it would continue to oppose anti-people policies of the Congress even while extending overall support to the ruling party. However, the CPI could manage nothing more than feeble protestations. The demonstrations it carried out against State excesses were, at best, half-hearted. How else would one explain the incident at the Delhi Boat Club? Here the CPI leaders, including the party chairman and 20 members of parliament, withdrew an agitation against the government at the appearance of a few policemen.

One wishes the author had deliberated more on the influence of international actors. Lockwood has mentioned a letter to Indira Gandhi from the Soviet leadership, sent on the eve of the Emergency, that warned about a conspiracy to "damage and destroy" all the leaders in the subcontinent who were responsible for the creation of Bangladesh. He has also talked about the influence of the global economy. But he has not quite explained if the Soviet factor forced the CPI's hand in supporting the Emergency. This angle would have added more depth to the analysis. It is also rather strange that the author never factored in the role of caste politics in his evaluation. As a commentator on Indian politics, Lockwood should have known better.

The CPI had to pay a heavy price for supporting the Emergency. It performed poorly in the next general elections held in 1977, and never quite managed to regain its former appeal among the masses. The CPI lost its premier status among the communist parties in India.