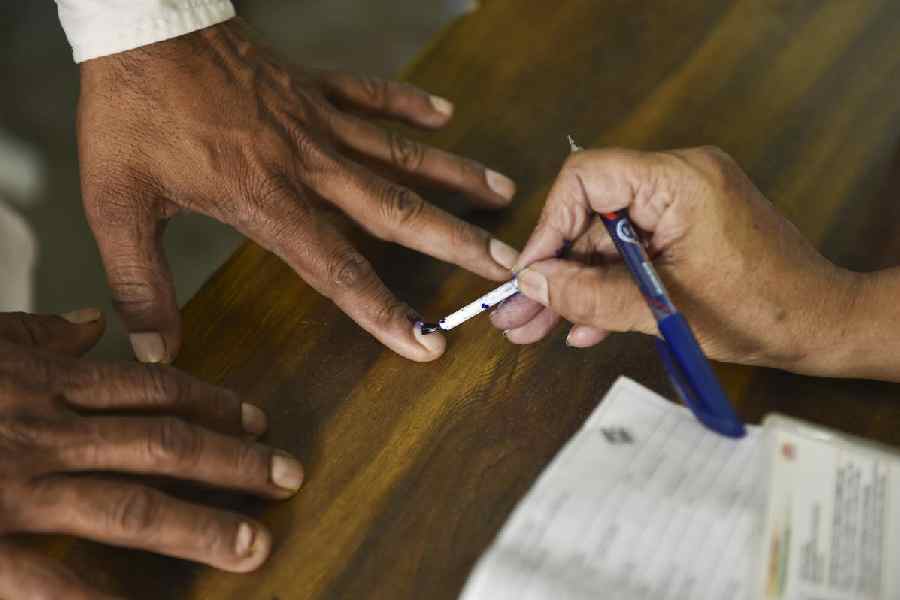

If elections are the heart of democracy, then participation in polls cannot be dismissed as a mere statutory privilege. It is thus heartening that the Supreme Court has sought responses from the Union government and the Election Commission of India on a petition challenging the blanket disqualification of prisoners, including undertrials and pre-trial detainees who have not been convicted, from exercising their right to vote. Section 62(5) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 imposes a blanket ban on voting for all prisoners, irrespective of whether they have been convicted. This provision is discriminatory because a person accused of a petty theft who cannot afford bail loses the right to vote while privileged citizens, including politicians, convicted of serious crimes but out on bail can stroll into a polling booth. Moreover, India’s criminal justice system rests on a principle older than the Republic itself: a person is innocent until proven guilty. Undertrials are not convicts. Many are in jail only because they could not furnish bail or secure timely hearings. According to the National Crime Records Bureau’s 2022 data, about 77% of India’s prisoners are undertrials, and the conviction rate for Indian Penal Code offences is barely 8.55%. This means that tens of thousands of citizens — most of whom will ultimately be acquitted — are deprived of their right to participate in an electoral democracy simply because of poverty, judicial delay, or administrative apathy. Worse, numerous surveys have shown that a disproportionate number of undertrials are from the marginalised sections of society. Disenfranchising them adds to cementing their peripheral identity.

Voting is an acknowledgement of citizenship. When the State withholds the vote from unconvicted citizens, it sends a message that their voices are less legitimate, that their belonging in a democracy is conditional. The right to vote is not contingent on physical liberty either. Many countries around the world have recognised this, and only those convicted of serious crimes are not allowed to cast their votes. While the administrative challenges of prison voting are real, they are manageable — after all, members of the armed forces vote through postal ballots and citizens abroad cast their votes through special arrangements. The Constituent Assembly chose universal adult franchise as an act of faith in the equality of all citizens regardless of caste, wealth, or education. This faith loses meaning when vast numbers of citizens — especially the poor and the marginalised — are excluded from participation not by conviction but by circumstance.