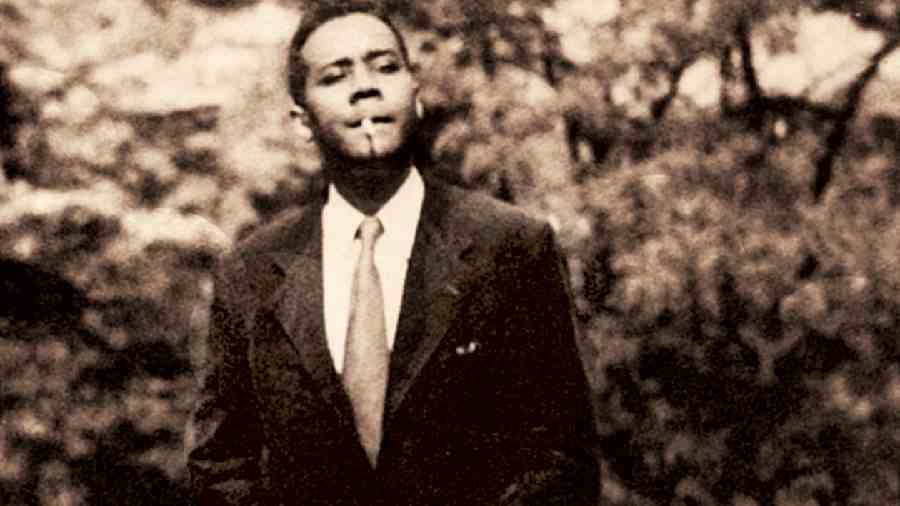

Newspaper columnists generally have the freedom to choose their own words, but rarely the title under which these words appear. Choosing an article’s headline is the prerogative of the newspaper staff who profess to have a better sense of what will attract the reader. Sometimes they indeed do. In forty years of writing for the press, the headline I most liked was given by a sub-editor at the now-defunct Sunday Observer. The article was about the Trinidadian writer and activist, C.L.R. James, to which the sub-editor had given the title, “BLACK IS BOUNTIFUL”.

The article was published in June 1989, shortly after C.L.R. James’s death in London, aged eighty-eight. I drew on my own reading of the man’s oeuvre and on a recent biography by the American historian, Paul Buhle. Like most Indian admirers of James’s work, I had come to him via his brilliant social history of cricket, Beyond a Boundary. I had first read the book in my college library, before picking up a copy (for the princely sum of four rupees) at the Third World Book Fair held in Delhi in February 1978. That copy has been with me ever since; although it is not a first edition, I value it more than many of the books on my shelf that are.

James was a great deal more than a cricket writer, of course. He was a pioneering social historian, the author of a landmark book on the slave uprising in Haiti that took place shortly after the French Revolution. Born and raised in Trinidad, he spent many years in the United States of America, active in Marxist politics. He had lived for extended periods in Britain and closely followed liberation struggles in Africa.

I have read (and read about) C.L.R. James obsessively for almost five decades now. The biography by Paul Buhle, mentioned above, was very insightful about his American phase, but weak (given the nationality of the author) on his cricket writings. I have read, with mixed feelings, a series of books and articles by professional academics on James’s legacy as a ‘postcolonial critic’, these high on jargon but insubstantial when it came to concrete biographical or historical detail. Also disappointing was the sole contribution by an Indian, a book by Farrukh Dhondy, purporting to be a full-fledged biography but in effect little more than a stream of unconnected recollections about James in old age.

James has long deserved a biographer who could do full justice to the richness of his personal life and the range of his public activities. He has finally found one in the Cardiff-based writer, John Williams. For his recent book, C.L.R. James: A Life Beyond the Boundaries, Williams has foraged widely in archives in England and the US, conducted many in-depth interviews with those who knew James, and closely read his vast and varied corpus of writings.

While James is inevitably at the book’s centre, Williams is alert to the significance of the other characters in his story. There are sensitive portraits of his friends from his Trinidad youth, of his lovers and wives, of his political comrades and adversaries in England, the US, Africa, and the West Indies itself. Among the most consequential relationships of James’s life were with the cricketer, Learie Constantine, the peripatetic revolutionary, Leon Trotsky, and the Trinidadian politician, Eric Williams, and these are narrated with sensitivity and authority.

While the book is largely sympathetic towards its subject, it is never adulatory. Williams is impatient with the sectarianism of the left-wing circles James moved in during his time in the US. He is also frank about the man’s prurient interest in attractive young women; this certainly worthy of censure in our own less sexist age.

In the course of his narrative, Williams provides us a stream of compelling quotations about and by the man. James was a fine writer but an even better speaker: as a young British woman (later one of his many lovers) wrote of a Communist circle in the London of the 1930s: “Normally, no one person monopolizes the conversation, and if they try, the others around feel somewhat irritated. In this case, however, everybody was completely fascinated by James. They would ask questions; I do not know if I did or not, but everyone was quite prepared and pleased to have him, more or less, give us a lecture on his subject.”

And here is the publisher, Fredric Warburg, on his author: “James himself was one of the most delightful and easy-going personalities I have known… [H]e stood six feet three inches in his socks and was noticeably good-looking. His memory was extraordinary. He could quote, not only passages from the Marxist classics but long extracts from Shakespeare, in a soft lilting English which was a delight to hear. Immensely amiable, he loved the fleshpots of capitalism, fine cooking, fine clothes, fine furniture and beautiful women, without a trace of the guilty remorse to be expected from a seasoned warrior of the class war.”

Next, consider this excavation by the biographer of a talk that James gave in the Lancashire town of Nelson in March 1934, in which he favourably contrasted the French attitude to people of colour with that of the British. James claimed that in Britain “the average person… did not understand the negro. They saw him only dancing and kicking his heels like a half-crazy lunatic; they screen him in an unfair position.” On the other hand, he argued, in France, “they would find negroes in the French cabinet, in the ranks of retired naval and army men, in the professions, universities and colleges. France had already disregarded scientific theories, and judged the negro on results.” Nine decades later, the comparison probably runs in Britain’s favour; in the long run, they seem to have done a far better job in integrating their African (as well as Asian) citizens than the French.

Williams pays proper attention to James’s two great books. Of The Black Jacobins, he writes that “CLR intended his account of the Haitian Revolution to be both a history and a blueprint for revolutions of the future.” And with regard to Beyond a Boundary, he gives us a rich, nuanced account of how the book was conceived, what it sought to say, and how it was received. He quotes from a letter that James wrote to Warburg in 1953, about the book he intended to write, which would radically decentre the English view of a game they had invented and thought only they understood.

In this letter, James explained the intention of his book as follows: “The God damned English writers with their elms and their green lawns and church steeples and eleven men playing cricket and the Englishness of it, are all going to be thrown in the dustbin. They have to explain why in India, in Ceylon, in the W[est]I[ndies], and in places where there are no elms and no church steeples but mosques and tom toms the game is played with more fanaticism than in England.”

Beyond a Boundary appeared ten years later, and under an imprint other than Secker and Warburg. Williams notes that the book has its flaws. It jumps abruptly from one theme to another. Some sections read more like journalism than literature. Nonetheless, writes Williams, “there is ... so much to admire. Ideas that other writers would use to fuel an entire book are strewn around with abandon. The writing has the seductive power of a great speech or sermon. If one book sums up the multidisciplinary brilliance of its author, while also revealing his heart and soul, it is this one.”

As Williams was completing this biography, the Black Lives Matter protests were gathering shape in the US and elsewhere. Williams thought this coincidence proof of his subject’s prescience: thus, as he writes here, the ideas that James “put forward in his own time — of the importance of identity alongside class, of rebellion coming from below, of the leading roles of Black people, women and youth in political struggle — have gradually made their way to the forefront of political thinking”.

John L. Williams’s superbly researched and beautifully judged book surpasses everything so far written about C.L.R. James. I don’t think I now need to read any subsequent biography or critical study. But I shall certainly revisit Beyond a Boundary every other year, as I have done since I was in my teens.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in