The recent death of Frederick Forsyth brought back vivid memories of the time when I first encountered his books. In the early 1970s, I was hardly the only nerdish twelve-year-old in Calcutta devouring adult Anglo-American bestsellers. At some point around 1973, having inhaled Mario Puzo’s The Godfather and become devoted to Leon Uris’s Zionist myth-making, I began hearing word of this cracking new book called The Day of the Jackal. Soon I got my hands on it and a new thriller-merchant joined the pantheon of Ian Fleming, Alistair Maclean, Puzo et al.

TDoJ gripped me from its very first pages, and very differently from the spells cast by the other writers. It is August 1962; the motorcade of the president of France makes its way through central Paris to the outskirts; lying in wait for General de Gaulle’s Citroën DS is an ambush by treasonous French army officers who want to kill their former commander for allowing the French colony of Algeria to become independent. The ambush is launched, semi-automatic bullets smash into the Citroen, two of its tyres blow out. As always, de Gaulle stays calm under fire while his driver takes brilliant evasive action, managing to get away from the shooters. The difference in the writing was the way in which totally believable detail was woven into the story to propel the action. The boulevards and the avenues of the route taken by the motorcade were named in sequence, where the bullets hit and how the driver (also named) handled the limping vehicle are described minutely, the immediate aftermath, where some of the conspirators are caught and executed, is coldly and precisely depicted, almost as if in a

news report.

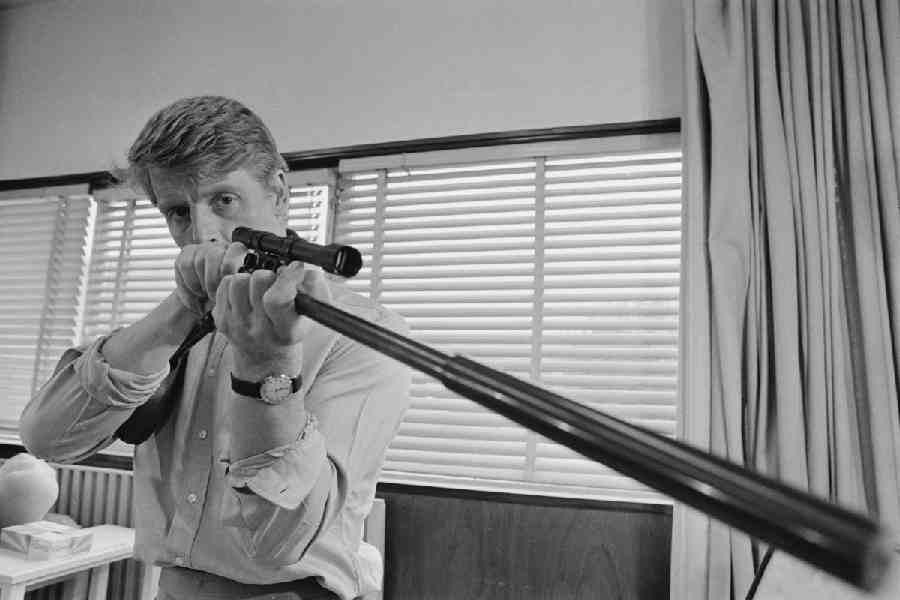

Given this mastery, you are gently but firmly pushed into believing the rest of the story as it unfolds. The French security forces begin to hunt the OAS, the group of rebel officers trying to kill de Gaulle. The leaders of the group hole up in a highly-guarded top floor of a hotel in Rome. Their only hope now is to kill de Gaulle before he kills them but the Secret Services have a thick dossier on every conspirator who can possibly carry out another attack. The rebels organise a mind-boggling amount of money and hire the best sniper-assassin in the world, a nameless man, probably English, who gives himself a codename for the operation — Jackal — Chacal in French.

The Jackal comes with a formidable CV of high–profile kills but his most remarkable hit was in the Dominican Republic where he ensured the death of the notorious dictator, Rafael Trujillo. Now, it’s a recorded fact that Trujillo was ambushed in 1961 while travelling in his big American car on a road outside his capital. What Forsyth adds is that the car was heavily armoured and unstoppable except for one small Achilles’ heel — the little triangular windows at the front were not armoured. The shot the Jackal took penetrated this triangle on the driver’s side, killing Trujillo’s chauffeur and sending the car off the road, after which waiting guerrillas moved in to finish the job. Driving in our family car, I would often examine the Ambassador’s similar triangular windows, marvelling at the shooting skill that might bring a lethally accurate bullet through it.

As many obituaries have pointed out, Forsyth’s manuscript was turned down by several publishers before being accepted. Apparently, the biggest reason for rejection was that de Gaulle was still very much alive at that time (to die a peaceful death shortly afterwards) and the publishers were convinced that readers would not be interested in a semi-factual story of which the outcome was long known. Among the things these rejectors failed to understand was that a nail-biting tale could be constructed as a counter-history that dovetailed into what had already happened in reality. As we follow the Jackal’s meticulous (and in the writing, meticulously detailed) preparations and his narrow escapes as he closes in on de Gaulle, what we don’t know is how close he will actually get and how he will finally be thwarted, and that is good enough.

As a character, the Jackal is, again, fascinating: he has no back story, we don’t know how he got into this profession, he has no trace of family or friends, we don’t know much about his emotions as he ruthlessly kills anyone who gets in his way. In terms of ‘branding’, whereas James Bond likes to introduce himself and the Corleones always make a point of underlining their name and the position of ‘Don’, our assassin only goes by various aliases and his codename, dialling a mole inside the French Security Services from phone booths and simply saying, “Ici Chacal”.

Thinking about it today, like The Godfather, TDoJ is a parent of many ideas we now take for granted: if Puzo’s book brings out the notion of the ‘Family’ with a capital F as a criminal-tribal-political enterprise, TDoJ gives us the lone, shape-shifting hunter stalking human prey with the help of devilishly clever technology, something we see in different avatars from the Terminator movies to the Jason Bourne franchise and beyond; without using the word, TDoJ also gives us the clearly-flawed notion of ‘decapitation’, the elimination of a leader or a ruling group that will lead to the collapse of its power hierarchy and ideology; the idea — shared with The Godfather — that nobody is completely safe, that “you can kill anyone”, as Michael Corleone says in the second Godfather movie. Besides larger trends, TDoJ also manages to touch on all sorts of things in passing. For instance, in the Jackal’s CV are included two neatly-shot German scientists, a duo working to develop a nuclear weapons programme for Egypt, which presage the more spectacular recent hits by the Israelis on Iranian nuclear scientists. Today, seeing reports of how precisely remote Israeli weapons seem to have decimated the Iranian leadership, the idea of a man with a rifle, no matter how sophisticated, does seem to belong more to the 19th century than the 21st and, yet, Forsyth’s first bestseller still stands as one of the most engaging fictional depictions of this kind of thinking — the idea that you can remotely kill a political figure surrounded by the highest security and get away with it.

On the other hand, even as we say goodbye to an author who gave us many entertaining books, we cannot ignore his unfortunate politics. Unlike a far greater ‘thriller’ writer, such as John le Carré, Forsyth remained uncritical of Israeli, specifically Zionist, policies. He supposedly backed, or was very friendly with, White mercenaries planning coups in Africa. For a man who made millions using Europe as the site for his books, he was bizarrely and stupidly a great supporter of the disaster called Brexit. Though a lot of his writing was gripping, in the final reckoning, Forsyth was a typically conservative, Anglo-Saxon man from the immediate post-War generation, someone for whom the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Israel were ultimately always the good guys. Now, as with his greatest character, the Jackal, there is no escape for Forsyth. Even as he exits, the inevitable variations and the ironies of history begin to swamp the man’s fictional imaginations, ageing some of his books terribly, degrading others even more radically.