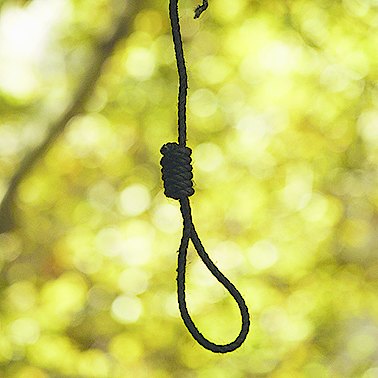

HANGWOMAN: EVERYONE LOVES A GOOD HANGING By K.R. Meera, Hamish Hamilton, Rs 699

This book is a fictional tale of a hangwoman, who is about to make her first execution. The subtitle is not meant to be sarcastic but to reflect the point of view of a hangman or a hangwoman - for who else other than them can love a hanging. A hangman earns his living when there is work. And work that sustains him is, ironically, that which extinguishes the life of another person. Human rights movement against capital punishment has deprived the executioner of his work, in India as well as in other parts of the world. K.R. Meera may have taken up such a subject to challenge our notions of good and bad, for the lines blur after a while.

When the chance to tie the noose came after 10 years for Phanibhushan Grddha Mullick, the hangman who had executed 451 men in his lifetime, he decided to hand over the baton to his daughter. The decision creates quite a stir in the country and brings the media to the nondescript house of the Mullicks on Strand Road in Calcutta. The house is located near a Kali temple that resounds with the shrieks of sacrificial animals; a tea stall that is thronged by people who carry dead bodies to the Nimtala Ghat; a parlour, which men use before and after returning from the ghat - death seems to hang over the place and weave itself into everyday life, unlike in other parts of the city. The house of the Mullicks also has august company. It is not far from Jorasanko Thakurbari and the Kumortuli, famous for making clay idols of gods and goddesses. But then there is also Sonagachi, infamous for being a prostitute quarter. The image of the prostitutes, however, changes towards the end when it is argued that, "The statue of Durga is made out of soil taken from the beshya's doorstep." Similarly, there is Mechua Bazaar, where instead of fish, they sell fruits; and Jatrapara, which houses the offices of the drama troupes of the city. It is in between these contradictory settings that the story unfurls.

The house of the Mullicks is at the centre of the plot that witnesses quite a few deaths in the family. The story begins with the executioner's daughter taking up the responsibility of despatching Jatindranath Banerjee to the gallows, a man who had raped and killed a young girl. Chetna, the daughter of the 88-year-old hangman is destined to carry on the dreadful tradition of the family. There is also a young reporter, who, struck by the beauty of Chetna, asks for her hand from her father. The story revolves around the family of the hangman, his son and daughter, their grandmother, an uncle and an aunt, and the reporter, Sanjeev Kumar Mitra. Sanjeev is a young reporter who is determined to create a niche for himself in the competitive world of broadcast media. Chetna too slowly starts to fall for the young man, but she can neither accept nor reject him. Her predicament mirrors the tension between a hangman and the one destined to wear the hood; one destined to kill, the other destined to be hanged at the gallows.

The novel is written from the point of view of the daughter of the hangman. Time and again it flits from the present to the past through tales that may not seem appealing to the reader. There are stories within stories that are interwoven around the history of the hangman's family, which goes back to 400 years before the birth of Christ. But it is also equally about the history of the city of Calcutta, its lanes and by-lanes, the coming of the British as well as the Nawabs of Bengal. Ironically these stories emanate from the unlettered grandmother, Chetna's Thakuma. The Plus-Two pass girl, Chetna, recollects the stories and passes them on to the readers in between light and serious moments, while she and the readers wait with bated breath for the hanging that keeps getting postponed. The hiatus is broken by the events in the household of the Mullicks and the professional life of the reporter. The love life of the two young people, which remains under the shadow of death, too helps in filling the void. Death also invades the executioner's household. Phanibhushan accidentally kills two of his family members and is thrown into prison. His son also meets an untimely death. But the hangman and his mother, Thakuma remains unfazed by death.

Thakuma is probably one of the most stoical characters seen in an Indian novel. She talks about death as others do of life. She does not shed a tear when her grandson dies. She remains untouched by sorrow when her son and daughter-in-law are killed by Phanibhushan. She does not bat an eyelid when Phanibhushan is thrown into the prison for the twin murders. But she is not insensitive; rather she teaches others how to face life even in the face of death. "'Poor Sudev, he's gone,"' she says, '"But well, he didn't come to stay in this world forever.'" Later on she tells Chetna: '"Irrespective of whether someone dies or is killed, it's all fated ... only fate...'" The unlettered woman has learnt the hard lesson from life. Death cannot be postponed and so it is useless to shed tears.

Meera not only tries to change the rules of fiction but also throws a challenge to history-writing where oral tradition vies with the authenticity of the art of the historian. Chetna's reminiscences are too many, her capacity to remember details and facts about her family and history of the country slows down the pace of the narrative. But if one takes the trouble to read the 400-odd pages, he or she will be treated with a series of tales about the history and culture of Bengal. Though Meera is from the south, her knowledge about the state can amaze even the most well informed. The book was originally written in Malayalam and has been translated by J. Devika.

Hangwoman deals with the theme of capital punishment, but it takes a panoramic view of life. It is in between the struggle of life and death that the real pleasure lies: just like the condemned man realizes before he is sent to the gallows. '"The real pleasure of human life,"' says the man at the last moment of his life, "'is hearing other human beings, experiencing their presence."' The book makes us appreciate the value of life in a way that we were not familiar with.