"Why is a raven like a writing-desk?" the Hatter had asked Alice. "I believe I can guess that," Alice had replied. But the March Hare insisted on precision. "Do you mean that you think you can find the answer to it?" he had asked.

"'Exactly so,' said Alice.

'Then you should say what you mean,' the March Hare went on.

'I do,' Alice hastily replied; 'at least - at least I mean what I say - that's the same thing, you know.'

'Not the same thing a bit!' said the Hatter. 'You might just as well say that "I see what I eat" is the same thing as "I eat what I see"!'"

The world of sublime nonsense that Alice eagerly explores in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (the second published in 1871) is produced out of overlapping games of logic, language, mathematics and science. The play changes at such dizzying speed that Alice is often "dreadfully puzzled", as happens further on in the conversation: "The Hatter's remark seemed to have no sort of meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English." Here what Alice is trying to hold on to is "meaning" that slips away when logic and semantics are overturned. But is meaning, or sense, accessible only in one way? Does not the magic of nonsense lie in the glimmerings of other, different, meanings, sensed through the 'nonsense', yet too fragile to be pinned down or elucidated?

Only a world where Alice is an alien can offer a route, however tenuous, to such different meanings. Even then they remain elusive. "Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas," says Alice of the poem, "Jabberwocky", in Through the Looking-Glass, "only I don't know exactly what they are." The principles on which "Jabberwocky" works lie at the heart of the play of language and logic in the Alice stories. The first verse appeared when Lewis Carroll was 23, in a 'periodical' for his brothers and sisters.

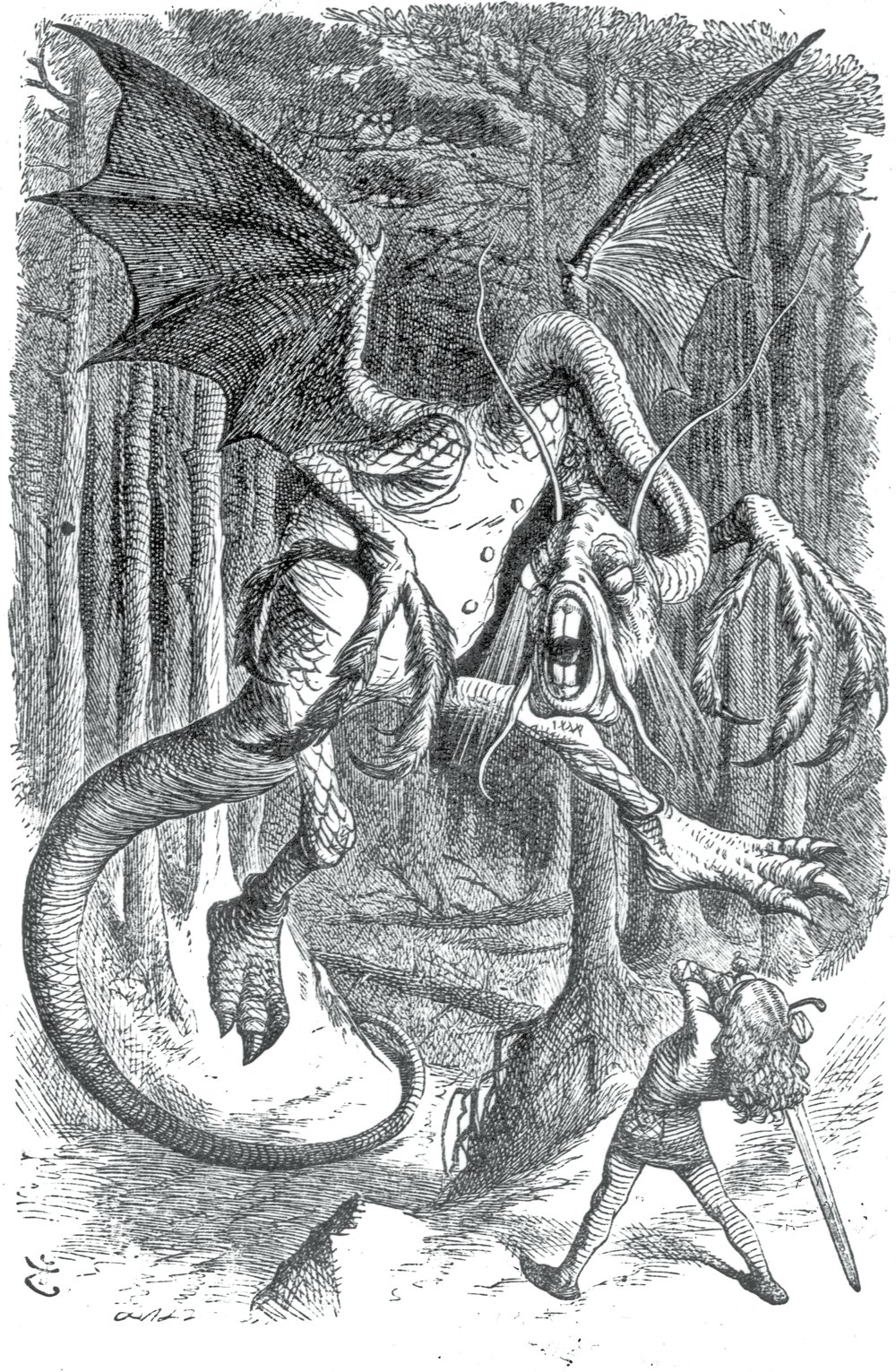

"'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves/ Did gyre and gimble in the wabe..." it began, plunging the reader into the "tulgey wood" where the hero stands in "uffish thought" waiting for the Jabberwock. Carroll has his own deadpan interpretation of the words of the first verse - borogove, for example, is an "extinct kind of parrot. They had no wings, beaks turned up, and made their nests under sundials: lived on veal" - and he called the verse a "relic of ancient Poetry". This was pure - and Puckish - fancy, but Carroll's comments at different times hint at the many ways in which creativity works. In 1877, he had written, for example, that "uffish" suggested to him "a state of mind when the voice is gruffish, the manner roughish, and the temper huffish." Almost every word is born out of a different creative dynamic, and the whole tempts the reader, like Alice, into a new world of brilliant sense. Only, we never quite reach it.