A recent Delhi High Court judgment upholding the dismissal of a Christian army officer for refusing to take part in the religious rituals of the Sikh troops he led offers an opportunity to consider not just the culture of equality in the army but also our legal and constitutional culture as a whole.

The officer, a troop leader of a Sikh squadron, claimed that he accompanied his troops for weekly “religious parades” involving rituals like pujas in a mandir and gurudwara. However, there was apparently no facility on the premises for other religions, and so he insisted on remaining outside the temple sanctum out of respect for his own Christian faith and the faith of his troops. His performance was otherwise exemplary, his bond with his troops strong, and his allegiance to the nation unquestionable. However, his request for an exemption was not considered, and he claims that he was subjected to harassment, ridicule, denial of opportunities, and adverse assessments as a result of his refusal to participate in the rituals of another faith. Finally, he was dismissed without court martial.

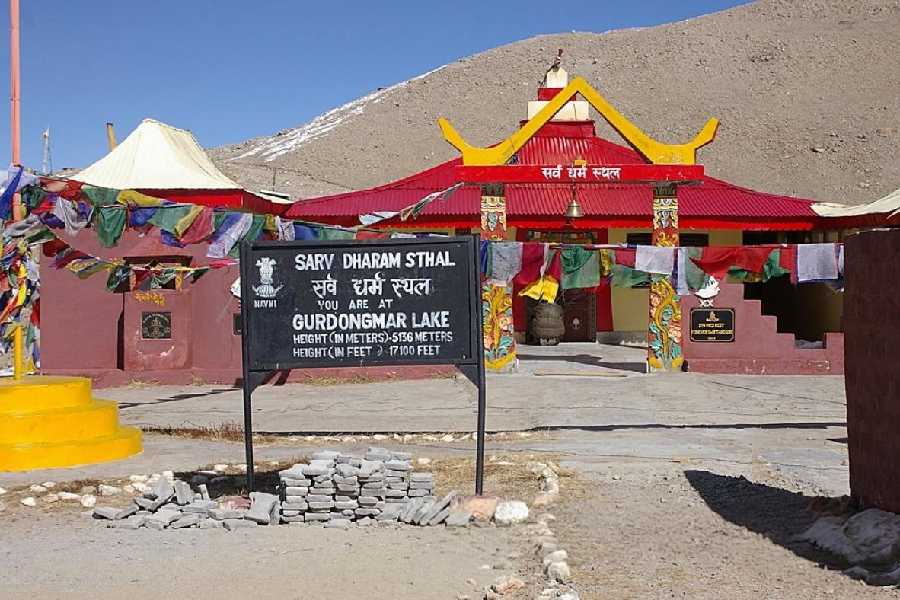

The civilian eye cannot be faulted for intuiting in this outcome a grave error. What civilised nation would require a person of one faith to pray to another’s gods as the price for offering his services in the defence of its borders? But this seems to be the norm. Many army units are drawn primarily or even exclusively from members of specific communities and they often engage in devotional practices aimed at fostering morale. Even some regimental war cries have religious character. And so the commanding officers of these troops are required to “adopt” the religion of their troops. This is an “essential professional responsibility” establishing a deep bond between officers and their troops. In service of the nation, attachment to one’s own faith must be abandoned and the established procedures and the ways of life of the unit must become one’s new religion as well as the bedrock of operational efficacy.

While forcing a person to “adopt” another religion and pray to its gods may at first appear to be a serious trespass into the sacred freedoms of conscience and faith, here it is transformed into a tradition that defines the very soul of a military unit and constitutes the shared emotional connection that troops rely on in unthinkably testing times. The high court agreed to this characterisation: these obligatory rituals had nothing to do with religion and only served a “purely motivational function”. Courts could not second-guess the decisions of military leadership about such matters. The transmutation of the puja from a religious duty to a military duty was, thus, the key reason why the judgment avoided questions related to religious freedom and discrimination.

It would be all too easy to stop here and say that artificial sentiments about liberty and equality are all so much meddlesome sand thrown into the eyes of the vigilant spirit of organic army discipline. But what underlies such a response is a trend that runs across our nation’s social and institutional practices. As per this view, there are some spaces where we cannot afford to reason finely. Just as sometimes it is a Christian army officer’s duty to enter a temple’s sanctum, in the Sabarimala temple, it is a woman’s duty to not do so. A classroom is a space where a hijab has no business. Religious laws on marriage, inheritance and the like are spaces where secular reasons must not tread. If the government decides that religion is relevant to questions of citizenship, courts should defer to the national security considerations involved.

These are not just fanciful extensions. If there are good reasons based in religious freedom for why religion-specific laws do not involve religious discrimination, courts are yet to articulate them. They either say that such laws are immune or that reform can proceed as per the government’s discretion, religion-by-religion. It is unclear whether supporters of this view realise that this is the same excuse offered for the 2019 Citizenship (Amendment) Act: that the protection of refugees from religious persecution can also proceed by saving those of some faiths first and others later whenever the government chooses. We find ourselves here because, across decades, courts have avoided giving a coherent answer as to when, if ever, discrimination is allowed. And they do this because we have made it so that they are afraid to engage with the question. There is evidence of this in the judgment mentioned above: not only were pujas exorcised of their religious character, but a court martial was skipped because it would lead to “unnecessary controversies”.

Community-specific military units may have colonial origins but they and their religious practices have been adopted by independent India with pride. Leaning on religion to weave the very fabric of army morale means, however, that we lean off what else troops could derive morale from. It just so happens that the devotional-yet-secular obligations of army officers fall on some religions and not others. Some don’t need to choose while others have no choice. These practices remained unquestioned because they took on a given social meaning. Embracing them without examination, we imagined that these traditions would march on into the future like unshakeable soldiers. But like everything else lifted up in the dust raised by the deepening of democracy, these practices too were bound to come under question, the useful illusions of the past curdling into sources of controversy.

Constitutional culture in India has uncritically accepted that seemingly incompatible values can be cherished simultaneously, and that insistence on principle is a symptom of juvenile naiveté regarding what truly makes a society tick. But we must consider whether this culture of contradiction and pragmatic enforcement is sustainable in the decades to come when wide publicity makes incompatibility more glaringly visible, or whether it turns this beautiful nation into a kingdom of consequences, not of consciences, the leniencies that once permitted pluralism now offering gateways for inequity to make inroads.

Lalit Panda is a Specialist (Rights and Regulation). Views are personal.