No matter how Britain’s 160,000 or so Conservatives voted yesterday, it is unlikely to have much impact on India or even on Indo-British relations. This would have been so even if opinion polls had not ruled out any chance of David Cameron’s 2015 promise to Narendra Modi in the packed Wembley stadium (“It won’t be long before there is a British-Indian prime minister in 10 Downing Street”) being realised when the results are revealed on Monday.

Cameron was of course trying to flatter his guest by saying that “British Indians [were] putting the great into Great Britain” even while The New York Times sneered at “Londonistan”. But Britain is still nothing like India where hearts are flaunted on sleeves. If religion is India’s ultimate reality, shouted raucously from rooftops and driven home with knife and bludgeon, race is the reality that dare not speak its name in Britain. Beneath the camouflage of political correctness, there probably still lurks the inhibition that prompted Robert Cecil, third marquess of Salisbury and three times prime minister, notoriously to wonder 136 years ago whether “a British constituency would elect a black man” to Parliament.

People commented even then that Dadabhoy Naoroji, the black man in question and unsuccessful Liberal candidate for Holborn, was paler than the ruddy marquess. The north London constituency of Finsbury Central made amends six years later when Naoroji’s election was “the first of its kind”, as C.P. Scott’s Manchester Guardian noted.

It’s not done in today’s polite society even to acknowledge the existence of race and colour. But at a dinner party in London the other day, a woman who had spent some years as a colonial burra memsahib blurted out, “Can you really imagine a hundred and sixty thousand or whatever people in this country voting for an Indian PM, especially all those blue rinsed Conservative women in twin sets and pearls.” It was a statement, not a question, all the more credible because the speaker herself, also in pearls and twin set, had been born in that world and married in it more than once although private conviction had taken her beyond its restrictive borders.

I told her of an elderly English couple in a large suburban bungalow who were all set to downsize when the first Race Relations Act was enacted in 1965. Since the new law explicitly forbade discrimination on the basis of colour, they decided to sell the house privately even though they knew they wouldn’t get the best price without advertising. “We couldn’t do that to the neighbours after more than twenty years,” they explained.

An email the next day from a scholarly woman of continental European extraction who had also been at table advised me not to believe that suburban attitudes had remained unchanged. She had discussed the Rishi Sunak-Liz Truss contest with a number of distinguished writers and thinkers and they were all of the opinion that Sunak lagged behind Truss only because of his unrealistic economic policies. “It doesn’t look as if he will make it,” she admitted, “but that wouldn’t be because of his origin or the colour of his skin. That has nothing to do with it.” She raised the conversation to a plane where the triumph of reason over instinct was as manifest as her own freedom from prejudice. “Neither candidate seems very appealing, though I prefer Sunak to Truss’ fantasies.”

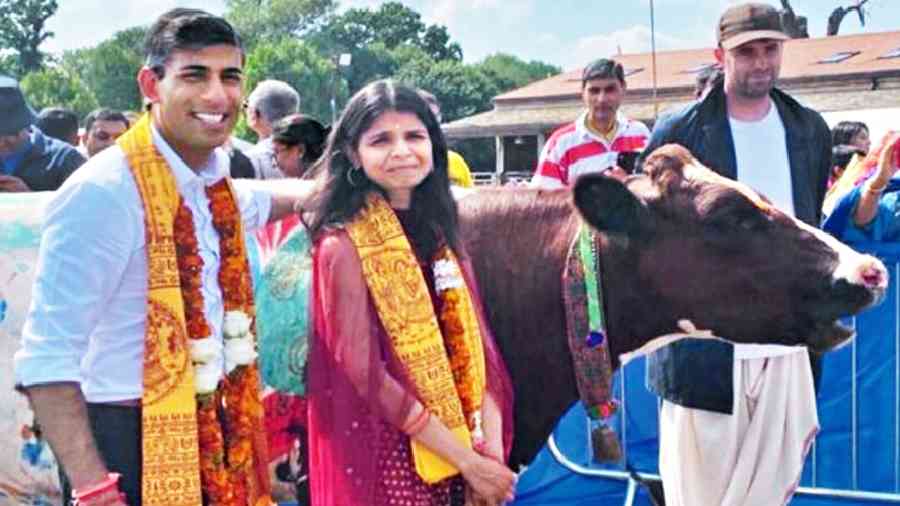

Another email sounded enigmatic on the face of it. My correspondent, an English diplomat whose wife and I had been at college together in the 1950s and who had taken early retirement to farm, assured me from the depths of rural England that “as good (Conservative) party members we have voted for the sub-continent’s takeover. But we doubt you will be getting an invite to Number 10 in September.” The intriguing last sentence may have been a reminder that contrary to glib assumptions about the power of the diaspora, India and expatriate Indians are altogether separate entities that might even be said to be historically estranged. For all his oath-taking on the Bhagavad Gita, gau puja and saffron scarf, Sunak is anxious not to be taken for anything but British. India is no more than a tactical fall-back position even for many non-resident Indians who are now flocking to the Hindutva standard.

The contrast was evident even when Cheddi Jagan, the first chief minister of Guyana whom Winston Churchill arbitrarily ousted in 1953, flew into Delhi to cries of “Jagan zindabad”. Convinced Nehru would take up Guyana’s cause at the United Nations and in Commonwealth forums, Jagan said, “We expect a great deal from India, as India is the champion of the colonially-depressed people, and has recently come out of the shackles of imperialism.”

He thought differently two weeks later. “I left India somewhat disillusioned” he wrote in The West on Trial. He was made to feel that he was “in the way” of Indian officialdom. Needing British and American assistance and being “preoccupied with its own Communists in Kerala, Hyderabad, and elsewhere,” India was inclined to listen to Britain’s anti-Communist propaganda.

Looking back, the disillusionment was entirely explicable. Until foreign remittances and the Uganda crisis induced an attitudinal change that resulted in the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas, India showed little interest in migrants. The unsympathetic attitude of our then elitist diplomats was matched on the other side of the fence by a rankling sense of grievance among people whom poverty had forced into exile.

Not surprisingly, the diaspora showed its true colours during the Gulf War when India faced stark bankruptcy with the foreign debt soaring to $70 billion and with shortterm obligations of another $4 billion. Expatriates who had gone abroad to do well and were doing well had no wish to be dragged back into India’s impoverished abyss. They invested in India when the going was good but scrambled out when things became rough. Of the $2 billion that NRIs moved out during the Gulf War and the political disruptions of 1991-92, a billion dollars were withdrawn between April and June 1991 alone.

Sunak, Priti Patel, Britain’s present home secretary, and also the Indian-origin attorney-general, Suella Braverman, whom Ms Truss has reportedly promised Ms Patel’s job, seem to make a point of distancing themselves from what can be called the Third World and its concerns. This seems to be the universal pattern. It was common knowledge that as Malaysian prime minister for 24 years, Mahathir Mohamad, was markedly disinterested in his Indian origins or in cultivating Indian diplomats. In contrast, David Marshall, Singapore’s first chief minister and a Baghdadi Jew with family connections in India, bravely ignored local Chinese jibes to declare that he would place himself “at the feet of Mr Nehru” to imbibe the latter’s wisdom before demanding self-government from Britain. Not being an economic refugee, Marshall, the Londontrained lawyer, had no hang-ups.

I have no knowledge of Sunak’s family circumstances apart from the well-publicised fact of his wife’s immense inherited wealth. Her reported ‘nom-dom’ status allows her quite legally to enjoy all the benefits of living in Britain while paying very little in British taxes because the bulk, if not all, of her income is earned abroad. Sunak, too, was always richer than his stories of serving behind the shop counter implied. His now surrendered green card, which he held even as Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer, made him a permanent resident of the United States of America, obliged to file US tax returns in that country.

This lack of rootedness is typical of the migrants’ paradise that is Londonistan. About 37 per cent of its inhabitants were born abroad, 24.5 per cent outside Europe. They cannot be expected to nurse any feeling for the country they left only to do better abroad. They will go where fortune beckons.