|

|

|

The past is not just the historian’s fief. Numerous artists — including photographers and painters — have also been enchanted by ruins of grand civilizations and attempted to capture their glorious accomplishments. These days, publishers, too, have entered the fray and shown a keen interest in printing works that chronicle the story of ancient regimes by combining research, text and image. VIJAYANAGARA EMPIRE: RUINS TO RESURRECTION (Niyogi, Rs 3,500) is yet another addition to this thriving genre.

Text and image, especially when they are used for a common purpose, seldom remain uniform in terms of quality. Unfortunately, in this instance, what unites text and image — by Usha and Raghu Rai, respectively — is their inclination to be ornamental. “The sunset and sunrise from central Matanga hill can be a blissful experience. The energy here is incredible” isn’t exactly an example of nuanced prose. Raghu’s bid to amplify the spectacular natural landscape makes his photographs particularly vulnerable to a kind of visual excess. One would have expected a more contemplative engagement with antiquity. Consequently, it makes it difficult for the discerning reader to differentiate both text and image from those that adorn elegantly designed travel brochures.

Usha redeems herself somewhat by presenting an uncomplicated rendition of Vijayanagara’s history. Lay readers, oblivious or indifferent to regal accomplishments south of the Vindhyas, would perhaps be surprised to know that word of Vijayanagara’s fame had reached to such distant kingdoms as Persia and Portugal.

The laurels showered on Hampi, the seat of the mighty empire, were on account of the success it achieved on numerous fronts — military, commercial and architectural. Of these, Usha lays special emphasis on Vijayanagara’s wondrous architectural legacy that survives in the form of temples, mandapas, zenanas, stables, most of which have been captured here on film. The fusion of styles that resulted in the incorporation of traditional Hindu structural elements such as gates, towers and pavilions with Indo-Islamic influences gives these edifices their syncretic character. Nationalist historians, who routinely cite Vijayanagara as proof of a golden, ‘uncontaminated’ past, would be perplexed by this confluence of distinctive traditions.

Of the temples, the Hazararama (top, right) and the Vitthala, the latter includes a dancing hall with pillars that produce musical notes, are bound to mesmerize readers. The British, unable to fathom the mystery, broke and took with them two pillars, only to find them hollow from the inside.

The text also reminds us of Vijayanagara’s success in the realm of civic amenities. The proof of immaculate and hygienic urban planning offers a sharp contrast to modern India, which has suddenly rediscovered the virtues of cleanliness with the help of its broom-wielding prime minister.

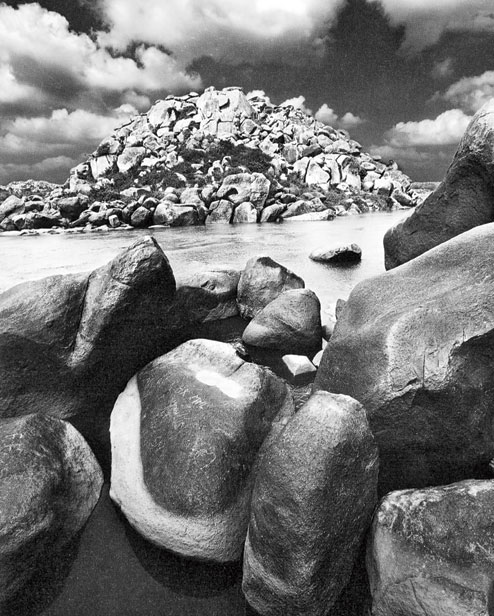

The photographs accompanying the text are certainly pretty. The section of black-and-white images depicting Hampi’s rocks reveals a strangely spartan world — rocky outcrops dominate the surroundings that are hardly sylvan (left). But Raghu’s photographs work best when they attempt to capture the ordinariness — even dreariness — of a life amidst splendid ruins. The poignant photograph of women fruit-sellers on the street outside a temple — tourism thrives in Hampi, which features on UNESCO’s global heritage list — illuminates a markedly utilitarian relationship with the past.

A book such as this isn’t a work of serious scholarship. But it does reveal the deft conservation efforts that have enabled the relics to survive (bottom, right). One can only hope that it will be able to kindle a flicker of interest in a nation whose past holds important, but unheeded, lessons for a not-so-glorious present.