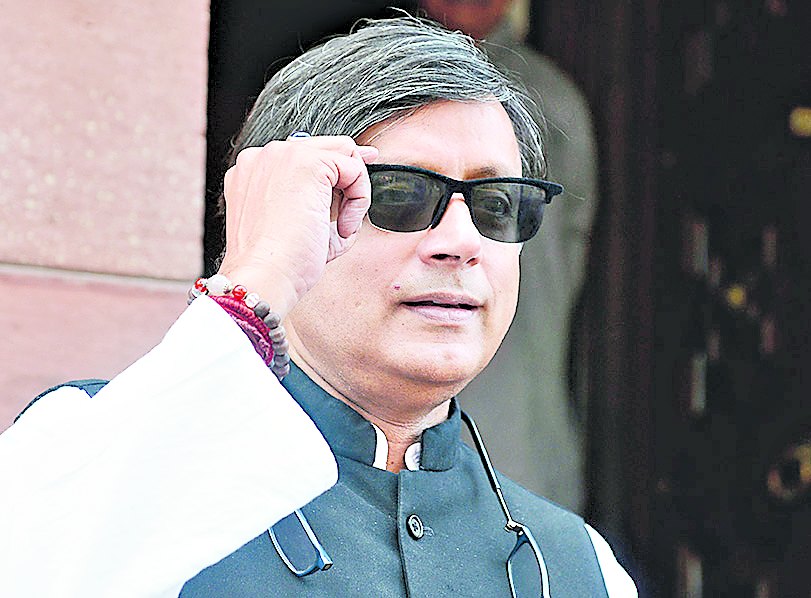

INDIA SHASTRA: REFLECTIONS ON THE NATION IN OUR TIME By Shashi Tharoor,

Aleph, Rs 695

A fair bit of trouble - personal and political - has blown Shashi Tharoor's way in the recent past. It is quite remarkable that Tharoor still found the time to reflect on what is troubling the nation that is experiencing unprecedented changes in such myriad spheres as politics, economics, culture, the media as well as governance. India Shastra, according to Tharoor, concludes the trilogy of works which are nuanced explorations of what constitutes the nation that is at once diverse and complicated. (India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond and The Elephant, the Tiger and the Cellphone are the other two volumes.) The choice of the word, shastra, in the present title is illuminating. Tharoor, considered to be an insightful chronicler in some quarters, perhaps wants his readers to view his essays with the reverence usually reserved for rare scriptural works. It would be unfair to expect such veneration from the readers simply because of the familiarity of these essays: most of them have appeared as columns in esteemed publications.

The book has been divided into several sections, each of which is an exploration of a particular theme. But the logic behind the division is not always clear. The first part is a critical overview of the new government, and is thus distinct from, say, the third section which discusses the threads woven together to create the rich tapestry of India's political inheritance. But at other times, the themes overlap, not merely because of the consistency of Tharoor's self-righteous tone. 'Ayodhya' and 'Black Money', to cite just two examples, have been bracketed under 'Contentious Issues', while equally controversial topics such as terrorism, casteism, gender violence and sex education are discussed under the header that explores a society in flux. The decision to express opinions on these inter-related topics separately runs the risk of obfuscating the critical links that bind them.

Tharoor, as virtuous as ever, readily admits that Narendra Modi sent him a congratulatory tweet after the former's victory in the last parliamentary elections, a rare occurrence given the Congress's decimation in the polls. The prime minister would be disappointed to note that Tharoor remains unsparing in his criticisms of the Bharatiya Janata Party's double standards. Among other things, he mentions the BJP's flip-flops on the Goods and Services Tax, as well as Modi's decision to continue with the subsidy on sugar, a policy decision that the BJP had criticized vehemently when the party was in the Opposition. Given the shrinking space for divergent opinion in India, Tharoor's legitimate criticism of the prime minister's failure to check communal disturbances is likely to be attributed to a case of grinding the political axe.

What is surprising to note, though, is that years of diplomacy and a career in public life have not quite robbed Tharoor of misplaced idealism. What else can explain the fact that Tharoor remains a votary of 'consensus' when it comes to instituting a code of conduct for governors in a nation whose prime minister thinks nothing of making disparaging remarks about the main Opposition party during a diplomatic visit abroad?

Readers with limited knowledge of the nation's history would, hopefully, take back something meaningful from Tharoor's dissection of the legacies of India's icons. But first they have to inoculate themselves against the author's sermonizing. Even in this section, Tharoor does not quite suppress his political instincts. The chapter on Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel invariably refers to Modi's pathetic efforts to appropriate Patel's legacy. Things have come to such a pass that even erudite Congressmen can think of no other way of distinguishing Patel from Modi than referring to their contrasting performances during pogroms in different points of the nation's history.

What disappoints the most is the uncomplicatedness of Tharoor's inferences when he examines such tricky propositions as the competing demands of democracy and development. To suggest that "[t]he question of whether democracy and development can go together has been answered convincingly by India" requires a special kind of insularity that politicians seldom lack. This is not to suggest that Tharoor ought to be dismissed on every count. His caveat against civil society for its eagerness to poach the responsibilities of democratic institutions in post-Hazare India is perfectly valid. Unfortunately, Tharoor chooses not to dig any further. That would have meant confronting the dismal fact that the inherent weaknesses in India's democratic institutions - including Parliament - have strengthened the grounds for civil society's intrusions in the eyes of the people.

This quality of evasiveness - as also a subtle anxiety not to be caught on the wrong foot - undermines what could have been a forthright engagement with the country's troubles. Of course, Tharoor's eloquence makes it difficult to spot the prevarication. But then, a silver tongue is a must for a long and fruitful career in politics.