Two exhibitions that ran almost at the same time in the city proposed perspectives that were, if anything, contrary to each other. The solo show of Rajib Bhattacharjee at Range Gallery projected, with anxious trepidation, urban reality as troubled, fractured Spaces in Transition. In contrast, the Hyderabad artists presented by Mon Art Gallerie were blessed in their unwavering certitude and rootedness, unbothered by transitions of any kind.

Rubble thrown into one corner of the gallery with the charcoal drawing of a crane looming over it on the wall warns you that the urban cauldron, seen in Bhattacharjee's 'cityscope', is nothing less than an apocalyptic churning. With cities continuously simmering to the makeover mantra India was initiated into with Liberalization, the old is ruthlessly torn down to erect the new on its ruins. The artist's digital prints and paintings - the largest print is 40" x 168"- seem to telescope what may still be standing with debris that's exploding vengefully, as it were: fragmented quotes from rundown buildings like period balconies; visual refrains of rickshaws, trams, taxis tucked in here and there amid the tattered images; broken, shifting bars and grids with whiplash charcoal lines streaking across the oppressive darkness in sharp lassos; sunless, airless, architectural masses as vertiginous in their multi-level heights as choking in their claustrophobia, flying apart, disintegrating.

The visual riff in this makeover mantra is, not surprisingly, the crane. A monster with hungry jaws that, in the colographs, become grasping claws. It is also the protagonist in Bhattacharjee's video, whether visible or not. As hazy video footage, prints and drawings ceaselessly churn, the background score of his art plays out: stone chips being unloaded, hammers thundering, concrete slabs thudding down...

But the resplendent colours, stylized form and traditional iconography of the Hyderabad artists tell you two things: that they are far from the madding disintegration of cities that Bhattacharjee frets over; and that this kind of art, far from contemporary trends, could never be accused of abstruseness or subversive intent and thus stands a fairer chance of gracing many a collection.

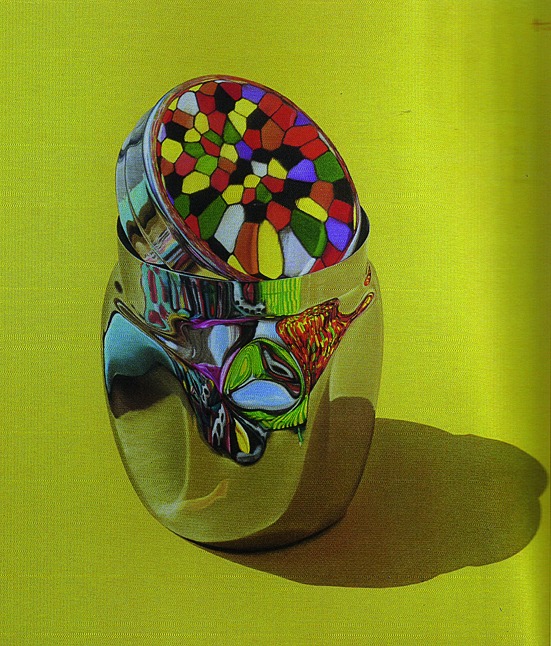

The well-known Vaikuntam focuses, as always, on dark-skinned, angular village folk from Telangana in their flaming yellows and reds. Gaunt Telangana women also seem to claim the attention of P. S. Chary, no pushover for being self-taught. In fact, his jagged lines and wiry forms remind you of Laxma Goud. More interesting is G. Anjaneyulu, who cunningly mines and mixes Subodh Gupta and Anish Kapoor in his oil and acrylic canvases. Gupta's gleaming steel utensils - those levellers that cut across region, class and community, screaming out their subcontinental identity - are, what can be summed up as, the Indipop equivalent of wry, Warholian banality. These everyday objects are the staple of his art. On their smooth curves he paints images of beguiling distortions as though they were reflections, echoing the signature idea of Kapoor in works like C-Curve and Sky Mirror. However, his ploy of faux reflections can go beyond mere optical deception into unstated possibilities only if disconcerting hints of today's reality are woven in.

Coming to the paintings of L. Saraswathi and Rayana Giridhar Gowd, you could be perplexed as to how they'd strayed into an art show. Because the calendar kitsch of the former in romancing Radha and Krishna and the cutesy sentimentalism of the latter in imagining Krishna and Ganesh as babies with their mothers tell you that Indian modernism, with its cubist Durgas and Ganesh Jananis, has simply passed them by. As for Ramesh Gorjala, who appropriates the quaint iconography of manuscripts, excess results in diminished appeal. But Mohammed Osman's depiction of the divine couple of Hindu lore is redeemed by bringing the flat, interlinked figures in striking colours on the same plane. A somewhat similar idiom of stylization works in the case of Thota Laxminarayan, too.

But when it comes to Anjani Reddy's indulgent, feminine romanticism and the dainty women's faces of Sachin Jaltare, bathed partly in shadows and prettily lost in self-absorption, it becomes obvious that pebbles are often passed off as pearls. Still, Irvan Karunakaran can be forgiven for his poster art because of its unpretentiousness. Simple, too, are the works of D.V.S. Krishna, with their multiple influences, and the fetching trees of Bhaskar Rao Botcha, while Rajeswara Rao's watercolour, New Love, is touched with dark banter.

Sreekanth Kurva's opulent bulls and G. Rama Krishna's balletic poses in bronze are variations on established themes. That's also true of M. Sreenu's bronze tableaux, but their colloquial tone is refreshing.