Two points need to be reflected upon in the context of the Uniform Civil Code. First, is uniformity desirable for a diverse nation like India? Second, is tinkering with the constitutional protection granted to personal laws of every religion appropriate? The Opposition parties protested against a private member’s bill on the UCC as a dangerous ploy to foment polarisation. The Union law minister has asserted that there are writ petitions on this sensitive issue pending in the Supreme Court. But this assurance failed to allay the fears of Opposition parties.

Are personal laws based on religion an affront to national unity? Article 44, part 4 of the Constitution reads, “The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code...”. The aim then was to formulate and implement personal laws of the citizens which will be applicable to every Indian irrespective of caste, religion and sexual orientation. The Centre’s argument is that the much-delayed UCC will facilitate integration by bringing different communities on a common platform.

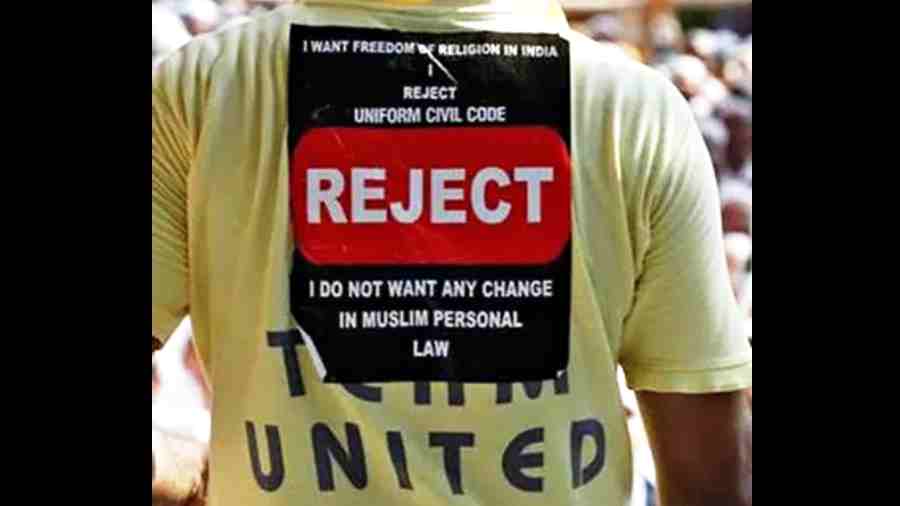

While India does have uniformity in most criminal and civil matters, the laws of anticipatory bail differ from one state to another. Experts opine that if there is plurality in codified civil and criminal laws, personal laws, too, should remain immune to interventions. There are genuine apprehensions that a UCC would ultimately be less about uniformity and equality and more about encroaching into personal laws of minority and tribal communities.

If the framers of the Constitution had intended to have a UCC, they would have included personal laws in the Union list and not in the Concurrent list. Even B.R. Ambedkar had an ambivalent stance toward a UCC. He felt that though desirable, it should remain “purely voluntary” in the initial stages. The dilemma persists 75 years after independence.

The chairperson of the National Human Rights Commission, Justice Arun Kumar Mishra, has advocated the implementation of the UCC, saying it will not disturb existing religious practices and ensure equal rights for women. But is the UCC actually a safeguard to save women from discrimination? In India, marriage is considered a sacrament in Hinduism; a contract in Islam; there is compulsory registration in Zoroastrianism. Those who are demanding it on the specious ground of women’s emancipation of certain communities should know better. A secular civil code may be the need of the hour but apologists of the current dispensation seem unwilling to shed their ideological tag. As for the tribals, a UCC may directly impinge on their customs including polyandry, polygamy and other practices.

The Union home minister, Amit Shah, has reiterated that a UCC has always been on the agenda of the Bharatiya Janata Party since its inception and that “religion cannot be the basis of the law of the land”. If the UCC is used as a tool of coercion to enforce regressive, upper-caste, Hindu cultural and religious practices on all citizens, it could lead to mass protests. India’s beleaguered liberal fraternity should be at the frontline of this potential mobilisation.

We must remember that the UCC neither promotes unity nor does it act as a buffer against gender injustice. The fear is that in the long run, it can soft-pedal the nationalist agenda of the current dispensation to discipline the aggrieved.