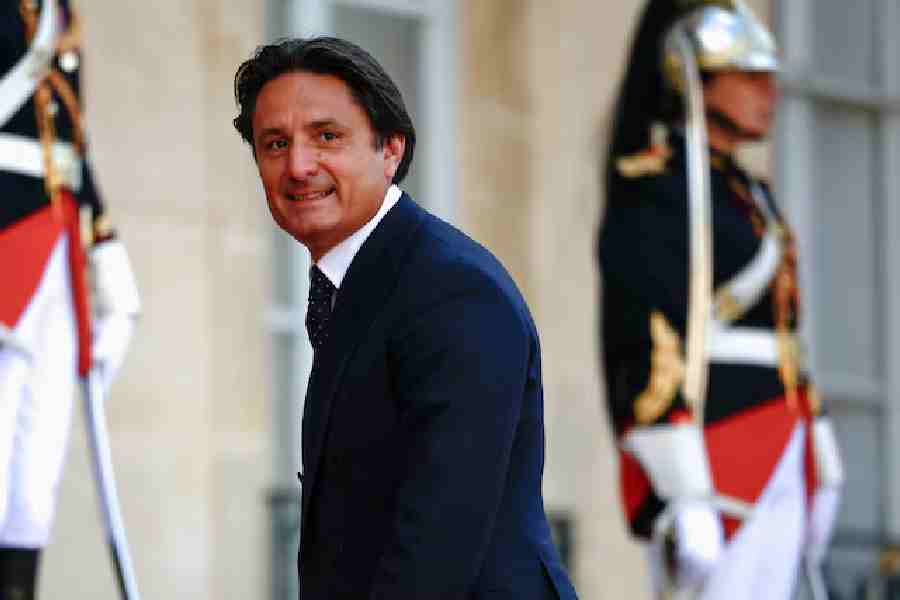

The Paris climate agreement completed five years recently. One can still remember Prakash Javadekar, India’s environment minister, saying, “All our demands have been met; we are going to call a press conference soon.” About half an hour after, a sulking Javadekar admitted at that press conference that India had accepted the agreement in the larger global interest despite its demands not being fully met.

Javadekar’s flip-flop reflects the ‘success’ of the Paris agreement. The agreement was a first-of-its-kind legally-binding emission cut document encompassing all countries. But its decision to permit a five-year emission holiday to major countries — the emission cut began in 2020 — was criticized. Moreover, the extent of the cuts was to be voluntarily decided by the nations themselves.

Five years down the line, global reports have pointed out that the world is still on course for a three-degree temperature rise by the end of this century with the industrialization era temperature as the benchmark. The Paris treaty had clearly stated that the temperature rise should be kept limited to two degrees, or even 1.5 degree if possible, if the world is to survive climatic impacts in the long term.

The alarm bell has started to ring, from the Sunderbans to San Francisco. In the Sunderbans, one of the poorest regions in India, millions are at risk on account of a combination of high- intensity cyclones and a record rise in sea levels. San Francisco, home to those with arguably some of the highest salaries in the world, has more than 20,000 households and 13 miles of highway at risk of permanent inundation due to sea-level rise. Clearly the risk, albeit buffered by varying patterns of resilience, is universal. Already, Covid-19 has shown that the world can be brought to its knees by a microscopic virus: climate change can do a lot worse.

The Paris agreement in its present form is not good enough to save the planet from climate change. The world needs to have an improved, pragmatic and expedited agreement to deal with the emergency called climate change. Some countries have announced deeper emission cuts, even zero-emission targets. These should become effective within another three to four decades. But we need to set targets for years, not decades. The global stocktaking of emission reduction should be preponed from 2023 to this year’s Glasgow summit. The prickly issue of historic responsibility concerning emission must be reconsidered; developed economies had forced its deletion from the Paris agreement.

The need of the hour is to shift from bigger, dramatic, long-term emission reduction targets to smaller, decentralized ones; let cities and even neighbourhoods have their respective targets that can be embedded in local development planning. Apart from making emission cuts easier, such a mechanism is likely to forge collective ownership and responsibility to combat climate change in a sharp contrast to the current top-down approach.

That evening in December in 2015 in Paris put the world on the right path. But the globe has been taking baby steps. It is now time to quicken the pace in Glasgow by setting aside narrow interests and geopolitical divisions so that the world can be saved from destruction.