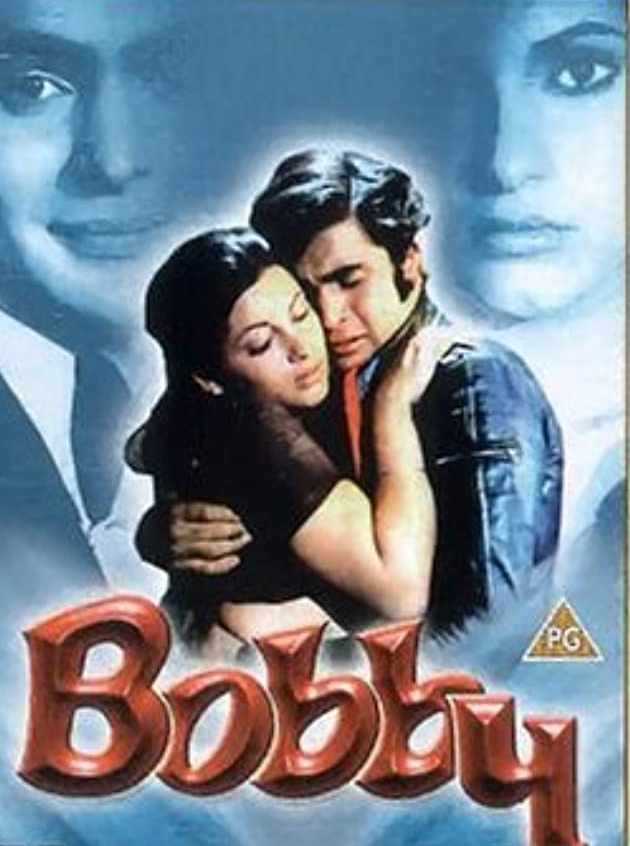

The deflowering — pun intended — of Indian cinema has its own timeline. Until recently, depiction of sexual intimacy in popular cinema rarely involved actual human beings in action. Consequently, directors had to rely on creativity that came dangerously close to the comic. The time-honoured metaphors of intimacy included the depictions of a fecund natural world: blossoming flowers, necking swans, the shaking bush — anything, presumably, would do to resemble coitus. At the other extreme lay all that was crude, but suggestive: the gyrating vamp epitomized this sexual undercurrent. All this was to circumvent the scissor-happy ‘censor board’ that refused to keep up with the times. Its holy grail, the Cinematograph Act, after all, had been framed way back in 1952. Of course, the odd film — Bobby is one example — did attempt to take the bull of morality by the horns. But portrayals of affection have been known to strike the match, quite literally. Fire, ironically, resulted in theatres being vandalized and vehicles set aflame — exposing India’s conservative attitude to sex in general and alternative sexuality in particular.

Films have come a long way since then and umbrellas no longer unfurl before a couple choose to lock lips. But umbrellas, or that shaking bush, could soon make a comeback. The villain of the piece, though, is Covid-19 and not the censor board. Even a lip-lock — forget a romp — while maintaining do gaz ki doori would need supreme acrobatic skills. The Producers Guild of India and the Cine & TV Artistes’ Association have already come up with changes in standard operating procedures to be instituted. Unsurprisingly, handshakes, hugs, kisses, and other forms of physical contact have been ruled out. Directors, consequently, are having to don their creative hats again. How would, they must be wondering, two masked creatures set the bedroom on fire?

But it would be hasty for florists to start fluttering in anticipation of burgeoning cash registers. The marvels of technology can make social distancing disappear with a single click in the editing room. Some film-makers have decided to turn to the future for help, plotting scripts where men and women romance androids and robots. Yet, it is the past more than the future that may hold the key to filming intimacy in the post-Covid world. Cinema — in India and abroad — has its own language and aesthetics of portraying warmth and emotions without resorting to explicit scenes. A poignant testimony would be the scene in Apur Sansar where a newly-married Apu, on waking up, pulls out his wife’s hairpin from underneath his pillow and smiles at the memory it evokes. Naseeruddin Shah’s gaze at Smita Patil in Mirch Masala lies at the other end of the spectrum of unreciprocated desire. These instances are masterclasses in the communication of various shades of passion and lust sans actual physical proximity. Covid-19 could lead to cinema return to this now forgotten language to light sparks.