The news that a hundred major monuments and historical sites are up for 'adoption' by private corporations, public sector undertakings and individuals under the government's 'Adopt A Heritage' (sic) plan came to public notice when the news broke that the Lal Qila had been given over to the care of the Dalmia Bharat Group for the next five years. A newspaper report quoted the company's CEO as saying "[we] have to start work within 30 days and have to own it for five years initially. Then the contract can be extended on mutually agreeable terms. It will help us integrate the Dalmia brand with India."

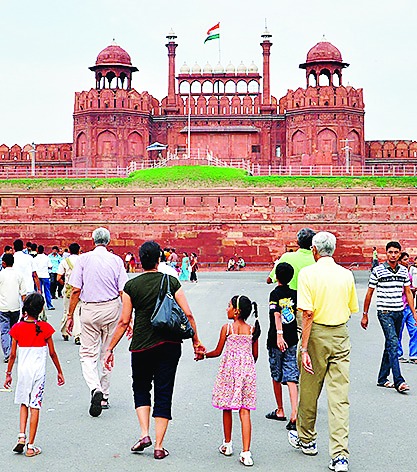

It can be said without controversy that integrating the Dalmia brand with India isn't a pressing priority for anyone except the company. On the other hand, the Red Fort is every Indian's business. Over the past century and a half, it has come to stand for India. From the revolt of 1857 to the INA trials of the 1940s, the fort became a sign for an insurgently nationalist India. When Subhas Bose said 'Dilli Chalo', Delhi was represented by the Lal Qila. When L.K. Advani campaigned on his rath in the mid-1990s, his pink, motorized chariot had Netaji painted on one side with the Red Fort in the background. This was meant to invoke the INA's intended assault on Delhi as a precedent for Advani's own. India's prime ministers have addressed the nation on every Independence Day from the ramparts of this iconic building.

So the Red Fort matters as do the Taj Mahal, the Sun Temple in Konark, Fatehpur Sikri, the Residency in Lucknow, Sarnath, the Sunderbans, Pangong Lake and India Gate, which are just some of the famous sites up for corporate 'friending' on the Adopt A Heritage website. These places are India; when a company's CEO says that its MoU with the government allows it to "own it for five years", it's reasonable for you and I as citizens to want to read the fine print of the MoU to understand the rights these companies will be given in these national heritage sites in return for their money and their managerial expertise. But more largely, the prospect of Dalmia Bharat managing the Red Fort and, possibly, the Sun Temple in Konark or GMR Sports being given some form of branding rights over the Taj Mahal, should prompt a national conversation on the relationship being proposed between private capital and national heritage.

It's worth saying here that non-governmental funds and expertise are not just welcome, they are essential for the preservation of India's heritage, whether these come from international bodies like Unesco, non-profit organizations like the Aga Khan Trust for Culture or private corporations. The idea that the Archaeological Survey of India along with the ministry of culture should have a monopoly over the care of India's built heritage has been comprehensively discredited by the track record of these organizations. Even the most famous Indian heritage sites are often uncomfortable, inaccessible, poorly maintained and badly conserved places that neither welcome nor inform their visitors.

The renovation and conservation of Humayun's Tomb and the monuments of Basti Hazrat Nizamuddin are outstanding examples of the benefits that accrue from an understanding among the ASI, the government's public works department and a private trust like the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The scrupulous restoration of the tomb of Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan led by the conservation architect, Ratish Nanda, of the Aga Khan Trust and supported by IndiGo airlines and the ASI is another public-private success story. If the Adopt A Heritage programme was using these as benchmarks for its MoUs, we could all rest assured. Alas, it isn't.

Since the memorandum of understanding between Dalmia Bharat and its government partners — the ministries of tourism and culture and the Archaeological Survey of India — isn't publicly available, the scope of this 'understanding' has to be gleaned from newspaper reports. It isn't clear from initial reports whether Dalmia Bharat's connection with the Red Fort is like the Aga Khan Trust's relationship with Humayun's Tomb (the responsibility for rigorously researched restoration and discreet credit for a job well done) or whether it's like Emirates Airways's relationship with Arsenal's football stadium (a quid pro quo that makes the site a billboard for the company's brand in return for funds and services rendered) or something in between.

There is a problem with the second sort of relationship when the places in question are heritage sites. What works with a sports stadium isn't a good model for sites that are seen in our collective imagination as 'national' or as sacred or definitive of some part of our country. We can all tell the difference between a sports arena called the Emirates Stadium and a water body called the Paytm Pangong Lake. Nobody wants the Reliance Rashtrapati Bhavan or the ITC Taj Mahal because the integrity of a historical site is tied up with its name. To change that name because of a business transaction is like making the Taj Mahal or the Sun Temple turn tricks for money. There is a reason why we don't yet have the Lacoste Louvre or the Walmart Washington Monument or the Virgin Westminster Abbey. Some names are best left unsold.

One newspaper reported that the contract "... allows prominent visibility to the Dalmia brand. The group would be able to use the 'Dalmia' brand name on souvenirs, banners during cultural events and all signage that it would install across Red Fort's precincts. A sign would also be deployed at the historical structure that shows that it has been adopted by Dalmia Bharat Limited. This would have to be done 'in a discreet manner and tastefully.' The size and design of such a sign associating the Dalmia Bharat brand with Red Fort would have to be approved by the ASI before it is put up on the 17th century monument or its precincts." This seems to suggest that sites for 'adoption' won't be renamed but leaves the magnitude of permissible branding undefined. As a first principle, the systematic identification of a heritage site with a corporate brand is a terrible idea.

The other problem with this initiative is that it isn't clear how one company is chosen over another. Unlike the Aga Khan Trust that has a long track record in heritage and conservation, Dalmia Bharat, GMR Sports and ITC bring no special expertise to the table. Is the right to manage these sites auctioned off? Dalmia Bharat is reportedly paying twenty five crore for the privilege of taking over the Red Fort. The newspaper report specifies the delivery of time-bound facilities for tourists like walkways and toilets and illumination. So, within a year, the company has to renovate toilets, illuminate the monument, build pathways and bollards, undertake restoration work and landscaping, and build a 1000-square-foot visitor facility. To do this without taking the time to research the archaeological history of a great monument is to virtually guarantee vandalism in the name of improvement. The restoration of Humayun's Tomb began after two years of intensive research. The thought of Dalmia Bharat building a 1000-square-foot visitor facility in or just outside the walls of the Fort inside a year is frightening.

The Adopt A Heritage initiative is a good example of a scheme dreamt up by an ambitious politician (in this case, the tourism minister, K.J. Alphons) to show visible results in the shortest possible time. It uses the success of the pioneering restoration work done by the Aga Khan Trust in the Humayun's Tomb and Basti Nizamuddin areas to justify the large scale entry of private corporations into heritage tourism, but skates over the professional expertise required to replicate that success. Bureaucratic inertia and incapacity are about to be replaced by corporate quick fixes designed to boost tourism. The potential for collateral damage is incalculable. Do we really want to run the risk of a company like Sahara or Kingfisher or Vedanta running Sarnath's Buddhist sites or the India Gate? Corporations should be encouraged to fund the maintenance and preservation of heritage sites and be credited for their efforts. But corporate social responsibility virtually demands that they shun administrative responsibility for these sites because it is so far removed from their core competence. A government that can't frame a grammatical title for its scheme — Adopt A Heritage — is unlikely to get much else right. The tourism minister should make haste slowly. Primum non nocere: First, do no harm.