On the hot and sultry morning of July 19, 1947, armed men in uniform burst into a building in downtown Rangoon and mowed down Aung San and six members of the Burmese interim government. While Thant Myint-U (grandson of U Thant) felt that it was not clear who the assassins of "this man with a strange and magnetic personality" were, Aung San's daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, pointed out that they were quickly traced to the home of U Saw, a former prime minister who had boycotted the elections. He was part of a leftist faction which believed that Aung San had gone over to the Empire in order to remain in power. Significantly, there were also some murmurs of British involvement.

So ended the brief life of an Asian leader who had struggled hard to find an acceptable ideology and relevant political strategy for a newly-emergent nation. Born in February 1915, it was not as though Aung San came from a family with political leanings or had role models to follow. His parents were "of solid farming stock", wrote their granddaughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, in Freedom from Fear, and though U Pha became a pleader (advocate), his legal career never really took off. While he "left an unflattering description" of himself as sickly, gluttonous and a late speaker, Aung San was soon obsessed with the desire to learn English, a prerequisite for higher education in countries under British rule. His daughter writes that Aung San had "as a young boy... often dreamt of various methods of rebelling against the British". At the age of 13, he moved to the National School at Yenangyuang, honing elocutionary skills that were to prove useful at Rangoon University. As was usual among middle-class families in the early decades of the 20th century, a visit to the photo studio was often mandatory, particularly for sons who had left home. There are a number of photographs of Aung San while at university, taken no doubt for his family, proud of their ambitious and clear-headed son.

While at Rangoon University, Aung San insisted on making public speeches, "interweaving his inadequate English with Pali words and phrases". He ignored the shouts that he should stick to Burmese, and soon "together with his moodiness, earned ... a reputation for being thoroughly eccentric, even mad" (Aung San Suu Kyi). In 1938, after finishing university, Aung San joined the 'We Burmese' organization that had its roots in the Indo-Burmese riots of 1930. Thant Myint-U reminds us that in the 1920s and 1930s, more than two-thirds of the inhabitants of Rangoon were ethnic Indians. They were among the country's wealthiest - businessmen, doctors and lawyers - "as well as its shopkeepers, industrial workers and labourers". Clearly, nationalist forces quickly overlooked the advantages of the Indian presence. Thant Myint-U also traced the history of "London's long indifference to Burmese concerns and sensitivities, [and] its treatment of Burma as just one more province of India". The Burmans (two-thirds of the population) were regarded as non-martial, unlike the Karen and the Kachin who were inducted into the Indian army and military police.

Aung San was a Burman, and it took little time for him to feel alienated from British policies. He wrote of "a very grand plan of my own" which ranged from boycott of British goods, strikes, marches, demonstrations to even guerrilla action and perhaps a "Jap invasion of Burma". However, the " petite-bourgeois origin" of his comrades meant that his views had little appeal. When the organization decided that its members should go abroad to seek assistance, Japan was the obvious choice. Soon Aung San and a few others received serious military training on Hainan Island. The Burmese Independence Army was officially launched in December 1941, and though it marched into Burma with the invading Japanese forces, disillusionment was not far away. A short-lived government run by the oppressive and cruel Japanese administration and the Burmese Independence Army presaged the emergence of Aung San as the commander-in-chief of the reorganized BIA, now known as the Burma Defence Army.

Japanese influence was well-entrenched in the country and though Aung San was invited to Tokyo in 1943 and promoted to the rank of major general, he kept "his own counsel and made his own plans". He soon launched the Anti-Fascist Organisation (later to become the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League - AFPFL) and decided to join the Allied forces against Japanese occupation. Thant Myint-U writes, "Student radicals had turned into partisans, and in 1945 the country was awash with weapons".

The British government decided that it was time to come up with a Burma policy and a White Paper advocating a representative executive council of political parties to advise the British governor. Though elections were on the cards, Aung San and the AFPFL demanded to be recognized immediately as the provisional government. By late 1945, "the 31-year-old Aung San was already wildly popular and his speeches were attracting huge crowds" (Thant Myint-U) - but London was not in a mood to listen to the governor, Dorman-Smith. Aung San flew to Kandy to meet Lord Mountbatten, supreme allied commander for South-East Asia. A new Burmese army was formed, comprising a mix of the original British Burma army and Aung San's Japanese-trained Burma Independence Army, most of whom were nationalists. It was not an easy mix, as the two halves distrusted each other and though 1946 was Aung San's year of ascendancy, with the nationalists refusing to compromise, a beleaguered Britain had little time to think of Burma. Dorman-Smith was replaced by Major-General Hubert Elvin Rance, well disposed towards Aung San. The two entered into negotiations and the Burmese leader was invited to London for talks.

In January 1947, Britain agreed to hand over power to Aung San and the AFPFL on the understanding that independence would follow shortly after. Aung San started consolidating his position in the cabinet as well as within the country. His lack-lustre election speeches were listened to with "quiet respect" and, as expected, in April, the AFPFL won with an overwhelming majority. However, "what happened next is seen by the Burmese as the central tragedy of their modern history", wrote Thant Myint-U. As all of Burma mourned its assassinated leaders, apprehensions over the future surfaced once more.

From the last years of the 19th century, as in other parts of the British Empire, many photographic studios had come up in Rangoon. Studio portraiture was an established middle-class tradition as was on-site photography. On July 21, 1947, as the Burmese capital was besieged with mourners, the photographer, U Mg Mg Gyi, who ran Myo Ma studio, positioned himself carefully and took photographs that have remained unknown for more than half-a-century. These were of Aung San's funeral procession, surrounded by army men and chanting monks. He took long shots of the cortege making its way down Sule Pagoda Road, flanked by elegant colonial buildings - being destroyed today by faceless modern architecture. These rare images remained unpublished as the photographer had no connections with newspapers or agencies. Later, following the military coup, it was only expedient to keep them hidden away.

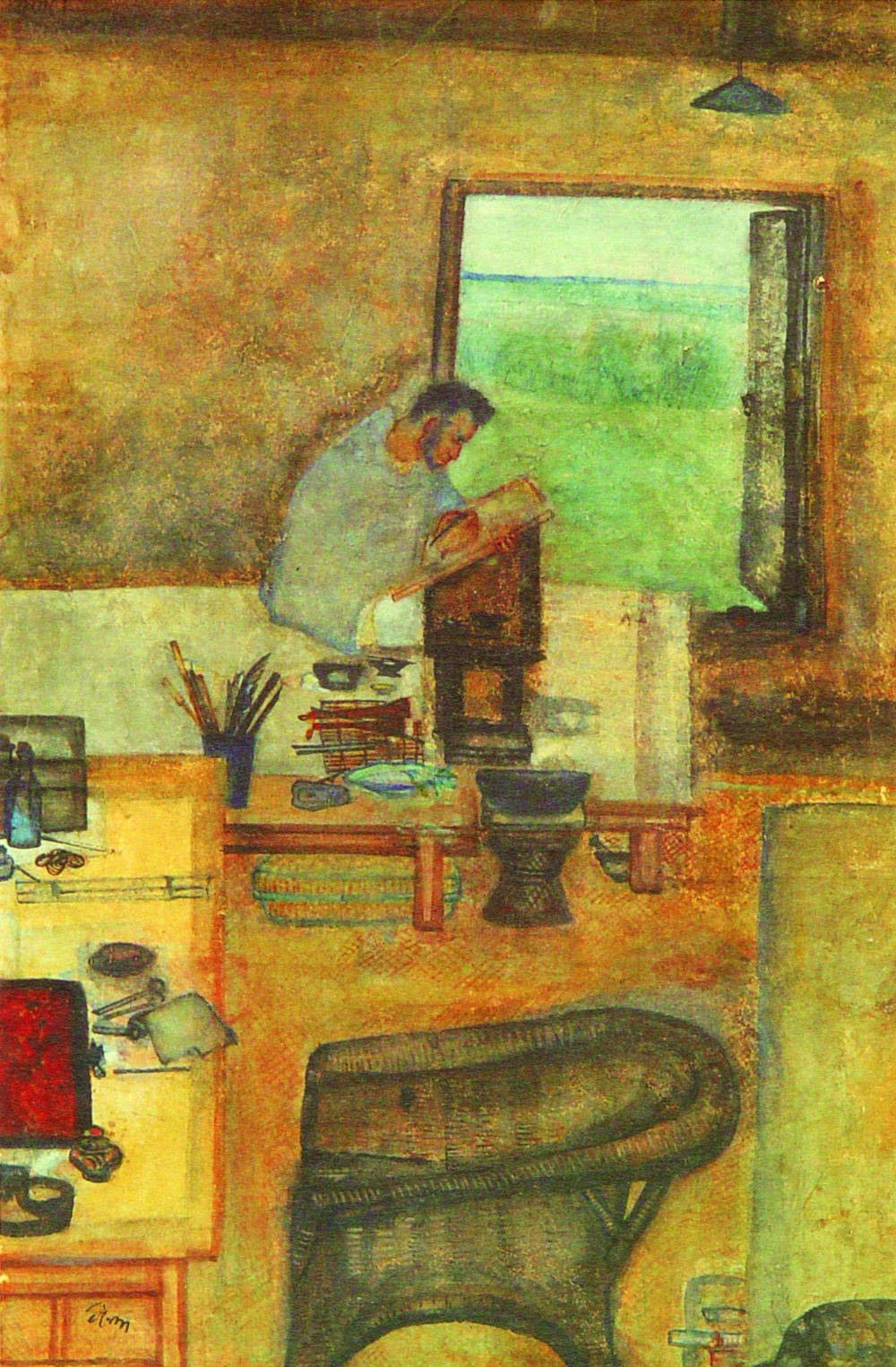

A couple of years back, Christophe Loviny, who has spent the last seven years training young Burmese men and women the skill of documentary photography, discovered that the father of his student, Tun Lynn, had these rare images taken by U Mg Mg Gyi, Lynn's grandfather,. Soon, in February this year, five were scanned, enlarged into more than poster-size images, and displayed at the Yangon Photo Festival (of which Loviny is the founder and artistic director). The specially created space was crowded with many viewers; young people, who had only heard of Aung San but are ardent admirers of Aung San Suu Kyi, were overawed by images of the crowds at his funeral procession and the older generation were teary-eyed as they remembered Daw Khin Kyi as a young widow with three infants. As he was known to the family, the photographer, U Mg Mg Gyi, was permitted to take this very rare private moment: Daw Khin Kyi mourning her husband with their two sons. When her father died, Aung San Suu Kyi was barely two, too young to realize much.

Photographs of Aung San in life and in death become vital at a time when the country prepares for general elections later this year. During his brief period of power and authority, General Aung San of Burma was photographed extensively in uniform, inspecting his troops, in London when there for talks, and on a visit to his elderly mother with his three children; there are charming images with his wife, Daw Khin Kyi and their three children - sons Aung San Lin, Aung San Oo and daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi. Without a doubt, photographs help situate the iconic personality firmly in the public imagination, and Aung San's life is no exception. Almost 70 years after his death, over-used photographic reproductions of the general in uniform appear on posters, buttons and flags - often in tandem with his daughter. The iconic image becomes a vital mnemonic device, a reminder of Burma's past struggle against colonial oppression. More than any other understandings of history, in the collective imagination, clever juxtapositions of Aung San's portrait with those of Aung San Suu Kyi synergistically bind pride in the past with hope for the future.

karlekars@gmail.com