MESSAGES FROM THE DEEP: THE WEST ENCOUNTERS THE RIG-VEDA By Sati Chatterjee, The National Council of Education, Bengal, Rs 650

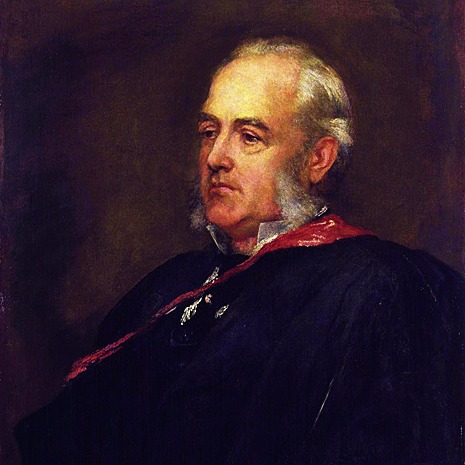

The great German Indologist and Sanskritist, Max Müller (picture), believed that the Rig-veda records the infancy of human (read Aryan) civilization. The 'helpless utterances' of primitive man in worshipful appreciations of the forces of the Universe represent "the lowest stratum in the growth of the human mind", and the adulthood of the Aryan mind is reached in Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.

In Messages from the Deep: The West Encounters the Rig-veda, Sati Chatterjee counters Max Müller's reading and recognizes that beneath the perception of the physical world there lies a deeper level of signification in Vedic hymns that projects a mature, self-reflexive and questing mind bearing the mark of a civilization at its apex. Müller's perception forms the basis of 19th-century Indology that assumes a linear development in human history - which is questionable.

The author provides archaeological evidence to show that the proto-theory of the Aryan invasion of India between 1500-1200 BCE is a myth developed by Western Indologists and philologists. Satellite surveys show the course of the Saraswati river, mentioned in Rig-veda, underneath the Rajasthan desert. The water from this subterranean course has been tested chemically and found to be several thousand years old. Manmade structures, relics and fossils found in the Arabian Sea near the Rann of Kutch and in the Bay of Bengal have been shown on carbon dating to be as old as the last Ice Age, that is, 8000 BCE. Excavation in 138 sites, including Mehergarh, proves the existence of a pre-Harappan agrarian Indus civilization with an advanced social life that is older than the Babylonian, Assyrian and Mesopotamian civilizations - and this is only the tip of a vast iceberg. So the Vedas are products of a full-grown ancient civilization which shifted to the Ganges valley after the Saraswati dried up. On the basis of astronomical calculations of stellar positions mentioned in the Vedas (when the vernal equinox was in Orion or when the Dog-star started the equinoctial year), Bal Gangadhar Tilak placed the Rig-veda between 6000-4000 BCE.

The enriched doxology of Vedangas and the transcendentally contemplative Upanishads or Vedantas are evidence of a developed culture and intellect, as is the Nasadiya Sukta, which speculates on the state of reality before the creation of universe.

Chatterjee unravels the reasoning behind Müller's interpretation to show that the colonial power-structure and Eurocentric egotism were its invisible spurs. The European conquest had two prongs - material expansion and cognitive or epistemic dominance. The epistemic encounter, in deciphering the cultural history of the colonized, embraces the contrary pulls of pure impartial intellect and imperial interests, along with the self-imposed responsibility to 'teach' the colonized. The epistemic conquest developed a strategy of owning and disowning the 'other' (colonized India) by announcing that 'future India belongs to Europe', marking the Vedas and Upanishads as alien. An imaginary timeline from infancy to adulthood placed an enlightened West at the helm and Indian heritage in a time-locked frozen era. Enquiry about the non-Western was intended only to prove the superiority of Hellenic culture.

The author recognizes Max Müller's lifelong scholarly dedication in exploring the Veda texts and Oriental ethnography. The scholar published the Rig-veda along with Sayana's exegesis under the patronage of the East India Company. But by deciphering the Rig-veda with the help of the bhasya of Sayana Acarya (written much later, in 1400 CE), Max Müller failed to appreciate that the Vedas integrate multiple layers of signification. The Brahmana tradition lays stress on the sacrificial aspect whereas the Aranyaka tradition reflects deep philosophical and spiritual realizations consolidated in the Upanishads. Sayana, a statesman-soldier in the time of the monarch, Bukka, of the Vijayanagara empire, felt the need to preserve the native identity of Vedic culture, at risk because of the Islamic invasion. So, in the Rig-veda- bhasya he emphasized the ritualistic aspects, thus boosting priest-craft or purohitatantra as a way to bind society within a well-knit religion. Thus wide thinking was reduced to narrow customs. Max Müller could not do justice to the Vedas by relying only on its ritualistic aspect and losing its core philosophical significance.

Several voices arose in 19th-century India against Müller's interpretation. Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay asserted that Vedic worship of many gods is not identical to Greek polytheism. Vedic poets tried to glorify the comprehensible, finite, numerous attributes of the Infinite Energy that is beyond human comprehension. This 'polymorphous monotheism' integrates surface and core, culminating in the Upanishadic non-theism or Atmavada. Aurobindo rejected the theory of Aryan invasion and held that "very far from being a childish or primitive and barbarous mysticism, this vivid, living, luminously poetic intuitive language is rather the natural expression of a highly evolved spiritual culture".

Upanishadic Monism holds that there are three levels of existence - ephemeral, practical and absolute. Only Brahman or Cosmic Self is absolutely real and cannot be sublated in any experience. Brahman-intuition reveals that the Cosmic Self is identical with the individual Self or Atman. All kinds of binaries and pluralisms dissolve at that transcendental level. In the Advaita Vedanta tradition this thesis has been established with sophisticated analysis.

The Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Vedanta movement brought about a resurgence of the Vedic and Upanishadic tradition. Ramakrishna urged people to relinquish dogmatism, declaring that different paths lead to the same spiritual goal. Vivekananda represented the Vedic tradition to the entire world as the universal and future religion - non-sectarian, inclusive and all-embracing. He appreciated Max Müeller's dedication to the study of the Vedas and said that Indians were indebted to him. But he was not uncritical of Müller and Sayana.

Chatterjee has brought out the essence of the Vedic message with profound scholarship and has thoroughly analysed the historical, social and political influences working behind Max Muller's interpretation. The work represents a postcolonial and transnational perspective on the subject.