Among economists' assertions that keep world democracies running, the pride of place is occupied by the need to improve growth rates of their gross domestic product, or its hallowed acronym, the GDP. Governments are voted out of power for failing to sustain acceptable growth rates, or into power for promising high growth rates. The reason underlying the public's faith in growth dynamics, though, is not entirely transparent. For the per capita growth rate of an economy, unlike most other gifts offered by a government, is neither physically observable nor consumable.

Be that as it may, the theory of economic growth is concerned with discovering ways of improving the growth rate of per capita GDP of a so-called free enterprise economy. The per capita GDP of the United States of America in 2017 was $59,501 while that of Ethiopia was $768. The renowned economist, Robert Lucas, was appalled by such diversities and moved on to locate possible reasons why some countries enjoy high levels of per capita income while others wallow in poverty. He ended by identifying inadequate accumulation of human capital, or a lack of widespread education, as the villain of the piece. An educated labour force improves productivity of all other forms of capital, machines, that is, and equipment, and helps to raise the growth rate of per capita GDP ever more rapidly.

Sporadic rises in rates of growth, of course, cannot contribute significantly to an economy's health. A high rate of annual growth, unfaltering over time alone can lead a country out of economic misery. In fact, Lucas had even come up with a rule of thumb for calculating the number of years required for an economy's per capita output to double, given a sustained rate of growth.

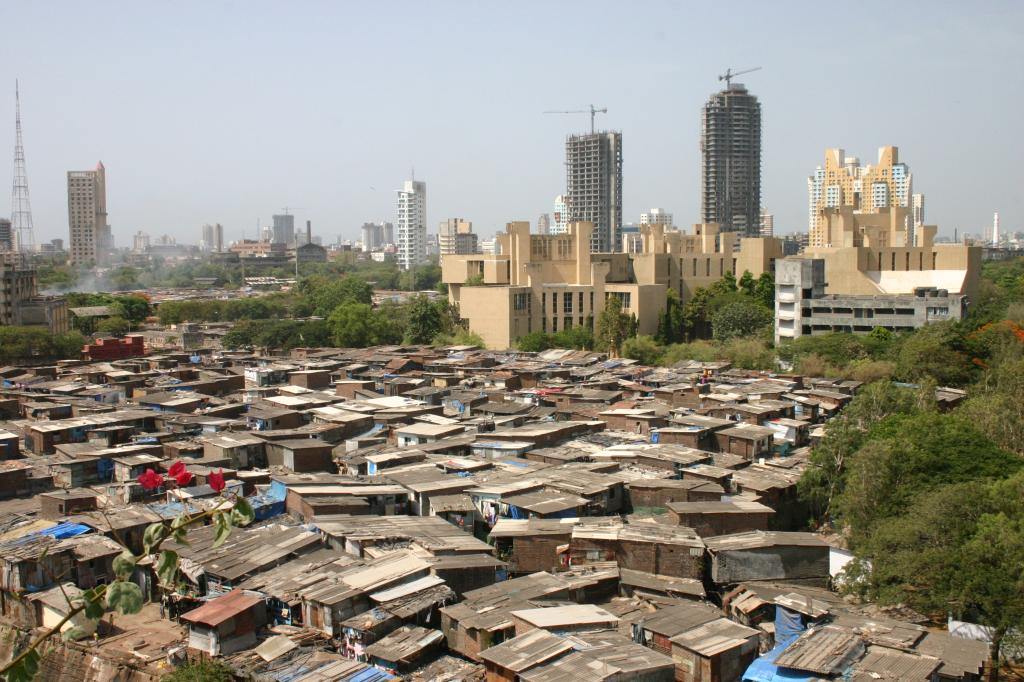

New questions, however, are being increasingly asked in this context. A high rate of per capita growth surely leads to a respectable level of per capita GDP. But is it meaningful to treat the dizzying heights reached by the per capita GDP as indices of low poverty? Growth needs to be inclusive, as jargon has it. In other words, the distribution of aggregate income associated with a growth path should crucially matter too.

An example easily clarifies. Consider a class of students, all of whom are five feet six inches tall. The average height of students in the class then is five feet six inches as well. If a new student, whose height is six feet is admitted to this class, the average height of students in the class will exceed five feet six inches even though all students in the class except one continue to be exactly five feet six inches tall.

The eminent columnist, Vivek Kaul, describes the matter more dramatically. The (unlikely) arrival of an Ambani into an Udipi restaurant in Mumbai raises the average income of people seated in the restaurant by "leaps and bounds". Kaul likens the phenomenon to a rise in the per capita income of people visiting the restaurant, even though the rise has next to no implication for the actual incomes of any of them other than that of the Ambani representative.

A high per capita GDP resulting from a high rate of growth, therefore, may neither be poverty alleviating, nor welfare boosting for the masses. While this conclusion is fairly obvious, let us ponder some more over the issue. The average or per capita income of a country does not, as we have seen, represent the income of the average person living there. This leads to a vital question. What, then, is the income of the so-called average person(s) in the economy? To identify this income, we need to part company with the per capita concept and replace it with the notion of the median income. Median income refers to an income class that has precisely the same number of income classes above it as it has classes below it. For example, if there is a society consisting of three individuals, earning Rs 100, Rs 200 and Rs 600 respectively, then its median income is Rs 200, as opposed to its per capita income of Rs 300. The average person earns an income of Rs 200 only, which is lower than the average or per capita income of Rs. 300.

If the theory of economic growth needs to address the question of welfare rise for average person(s), then the models and their policy implications need to recognize the median as the variable of interest, which, unfortunately, is not an easy task to accomplish. Further, even if mathematically sophisticated models are built to link up economic growth with the behaviour of the median income, empirical identification of the median itself will remain an even more challenging job.

A survey, it appears, was conducted, though, in 2013 and it had concluded that India's median income that year was $616. Kaul notes that the World Bank had estimated India's per capita income for the same year to be $1455. These figures led Kaul to conclude that India's average income was well above the income of the average Indian. The finding indicates severe inequality of income distribution in India, with the top income earners cornering the lion's share of the aggregate income generated in the country.

Going back to Lucas's prescription of human capital accumulation to achieve high per capita growth rates, the median income and hence the inequality of distribution begin to bring up serious questions. According to the National Sample Survey, the annual cost of professional and technical education has risen to somewhere around Rs 62,841, which, assuming an exchange rate of Rs 65 per US dollar, turns out to be approximately $967. The median income earner or the average Indian then, is hardly in a position to educate a single child without shouldering a burden of debt for an unspecified period of time. We are caught, it would seem, in a vicious circle. Unequal income distribution accompanied by an exorbitantly high cost of education permits human capital to be embodied mostly in the rich. The benefits of human capital growth in the form of higher incomes accumulates accordingly in their hands alone. And this, in turn, perpetuates distributional inequality.

The tension between per capita income and median income experienced even by economically advanced societies is closely linked to the notion of welfare states that are concerned about the middle class and not just the poor. Adam Smith's dictum that unbridled pursuit of self-interest acts in the interest of society may not have worked in the ruthlessly capitalist world. Liberal thinkers like John Stuart Mill had suggested public spending in areas like education and health, or a grain of socialism if you will, to ensure that the median person could live a respectable life, an objective that India's Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act fails to achieve.

Countries in the European Union appear to have succeeded to some extent in marrying off capitalism with socialism, without losing out either on growth or development. "Big welfare states", as The Economist quotes Will Wilkinson of Niskanen Centre in Washington DC, need to "become better capitalists to afford their socialism".

India will do well to keep such issues in mind in its desperate effort to outgrow China.

The author is former Professor of Economics, Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta