SIKKIM: REQUIEM FOR A HIMALAYAN KINGDOM By Andrew Duff, Random House, Rs 599

On a clear day one gets a distant view of snow-covered Nathu-la from the palace compounds in Gangtok. When I revisited the palace during a recent trip to the Sikkimese capital after nearly twenty years, Nathu-la, the Himalayan pass, was in the news. India and China had just agreed to open a new route through it for Indian pilgrims journeying to Kailash-Mansarovar in Tibet. Earlier in 2006, the two countries had reopened the old trade route through Nathu-la. The year before, Beijing had finally accepted Sikkim as part of India.

How it became a part of India is an old story that few in Sikkim - or elsewhere in the world - care to recall. For those who do, it remains "a Himalayan tragedy", as Nari Rustomji, one of the first Indian administrators in Sikkim and a lifelong friend of its last Chogyal, put it in the title of his 1987 book.

Andrew Duff's interest in Sikkim had its origin in the pictures his grandfather had taken during a tour of Sikkim in October, 1922. The beauty of the tiny Himalayan kingdom, captured in the photographs, fascinated him. But it was the tragic end of the kingdom that moved him to try and find out how and why it happened.

Soon after Duff began his research, he came to know how, after the British had left India in 1947, the Himalayan region had been at the centre of international intrigue across Asia, a "second front for the Cold War". He came to understand that the history of Sikkim's annexation by India in 1975 could not be seen in isolation. "Sikkim", he realized, "never stood a chance".

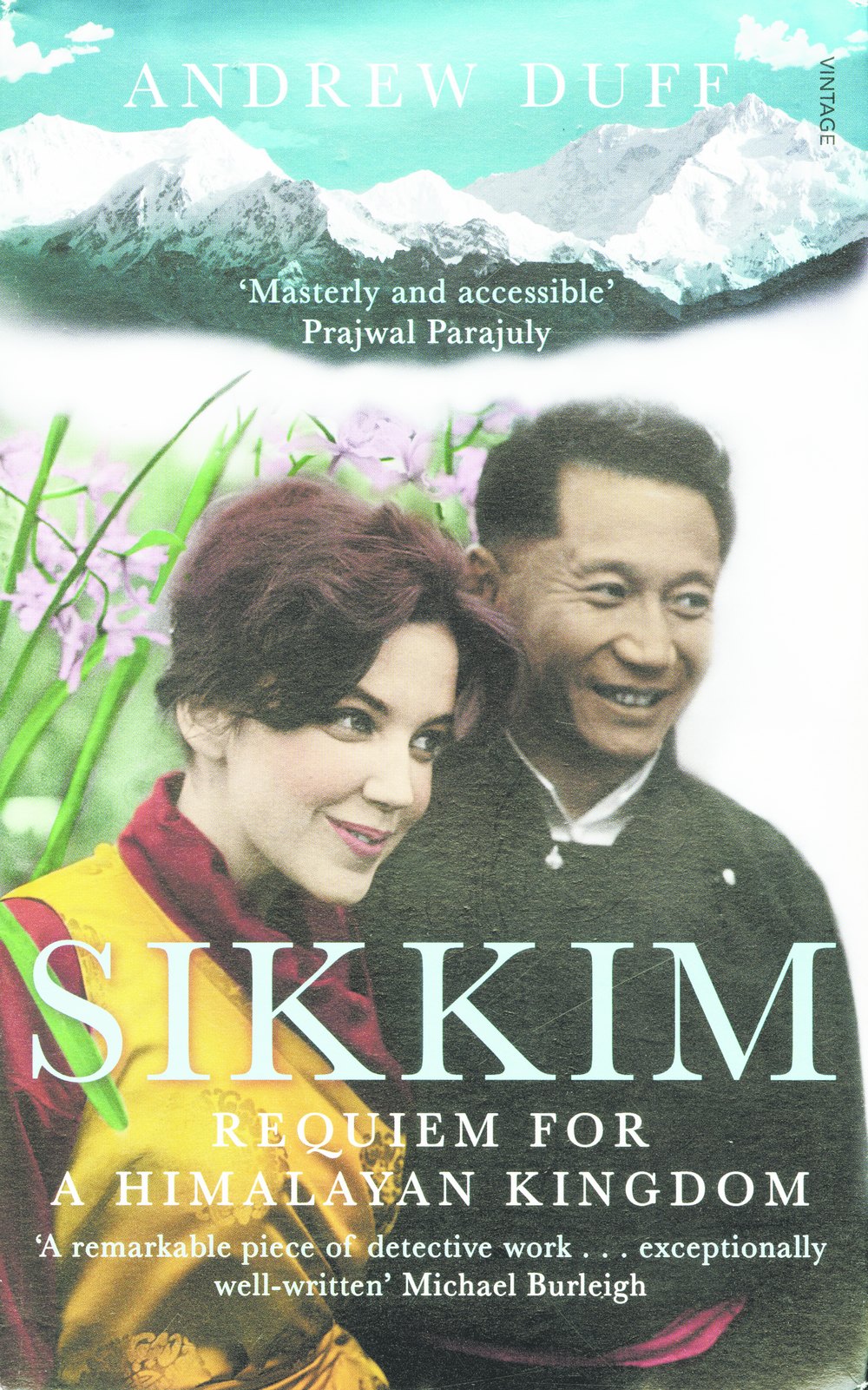

One man, though, never accepted that. Palden Thondup Namgyal, Sikkim's last dynastic ruler, tried everything to reclaim for his kingdom its 'place in the sun'. That, to him, meant a status that would make Sikkim, like Nepal and Bhutan, a member of the United Nations. He was aided in his campaign by a young American woman who had fallen for his charms during a chance encounter in a Darjeeling hotel and soon after became his wife. To the Western media, Hope Cooke, the young American beauty becoming the queen of a Himalayan kingdom was more of a fairy tale than Grace Kelly becoming the princess of Monaco.

But, as Duff's narrative shows, the romance was soon caught in the web of Sikkim's and India's domestic politics as well as of international power play in the region. Sikkim's location - on India's border with Tibet, which communist China had occupied in 1950 - turned the sleepy kingdom into a strategic hot spot. The Tibetan resistance movement, funded and armed by the Americans, the Dalai Lama's flight from Lhasa in 1959 and finally the India-China war of 1962 made Sikkim a crucial element in India's strategic planning in the Himalaya. Sikkim's affairs could no longer be left to the Chogyal. The more the king tried to claim what he thought was a fair deal for his kingdom, the harder New Delhi struck at him.

What New Delhi did to sabotage the Chogyal's authority and to eventually rob him of his kingdom is a familiar story. Duff draws liberally from earlier accounts such as Sunanda K. Datta-Ray's Smash and Grab: Annexation of Sikkim , Rustomji's Sikkim: A Himalayan Tragedy, B.S. Das's The Sikkim Saga , Cooke's autobiography, Time Change, and memoirs of Indian intelligence and administrative officers who played a major role in organizing and funding the democracy movement in Sikkim. A farcical referendum on the kingdom's 'merger' with India finally sealed its fate.

But the author also gets access to many other documents - private correspondences and official records, including a tranche of US-government cables recently released by Wikileaks - that throw new light on the bigger picture of the Cold War rivalries and their impact on Asian events of the time. Add to all this the complex political situation that Indira Gandhi increasingly faced at home. If the Indian army's victory in Bangladesh in 1971 and the country's first atomic explosion in 1974 were high points of her career, these were soon followed by her indictment by a court in an electoral malpractices case and the Opposition campaign against her led by Jayaprakash Narayan. The trouble at home forced her to declare the Emergency in June, 1975, only a month after the annexation of Sikkim.

During the run-up to the takeover, dramatic changes were happening on the Cold War front. The Sino-Soviet relations had collapsed a few years before, shaking the communist world. In 1972, Nixon-Mao Zedong meeting shook the rest of the world. After a humiliating defeat, Americans were busy completing their final withdrawal from Vietnam. In those heady days of Indo-Soviet friendship, the hand of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was seen behind everything that upset Indira Gandhi. No wonder the Chogyal and his American wife were routinely painted in official circles as playing the CIA's or Beijing's games. But Duff quotes a large number of British and US government records to argue convincingly that Sikkim did not figure much in diplomatic policies of Washington, Moscow, London or Beijing. Big powers were too busy with bigger issues to bother much about a small kingdom tucked away in remote Himalaya.

Duff is probably right - arrayed against such formidable enemies at home and in New Delhi, the Chogyal and his Sikkim stood very little chance. The book's portrayal of the Chogyal is clearly sympathetic but it is not uncritical. It shows how the Chogyal's fall was partly due to his own failure to come to terms with the changing reality. Nepalis had been settling in Sikkim for more than a century. By the 1950s, they comprised seventy-five per cent of the population. So the Chogyal's attempt to rule with the help of only the minority Bhutia-Lepcha community was doomed to fail. Just as futile was his hope to persuade New Delhi to accept his demand for a Bhutan-like status for Sikkim.

Yet, the Chogyal's fight is presented as heroic. By contrast, people like Kazi Lhendup Dorji, his enigmatic Scottish wife, their adopted son and the most vitriolic of the Chogyal's adversaries, Nar Bahadur Khatiawara, and most others propped up by New Delhi to play its game in Sikkim end up looking small. The wheel turned full circle for the Kazi. In 1995, the hero of Sikkim's pro-democracy movement publicly apologized for his role in it and demanded the state's 'de-merger' from India. Of course, the big villain in Duff's story is the Indian State. Its last act - of sending soldiers to storm the Chogyal's palace, killing one of his guards and placing the defenceless man under virtual house arrest - was the meanest in a tale of treachery.

Duff's is clearly the most comprehensive account so far of Sikkim's fall. The way he weaves the personal into the political and the historical shows a masterly skill in story-telling.