Early romantic crushes rarely endure, but early scholarly interests often do. I began my career as a historian of forest communities whose lives were rudely disrupted by British colonial rule. Though I have since meandered off into other directions, I have always retained a connection to the field I first began to till. In fact, I have spent the past week reading a doctoral thesis by a young scholar which explores the social and environmental history of what is now the state of Jharkhand. I was so struck by how good the thesis is that I thought I should write about it in this column.

The thesis focuses on the transformations of Adivasi society in the region of Singhbhum under British rule. It first documents how the East India Company steadily acquired military and administrative control over the territory. It then examines how colonialism radically reshaped the natural landscape, the legal framework, and the economic and political structures of Singhbhum. Among the important themes covered are the commercial biases of colonial forest policy, the changing status of village headmen who had to negotiate with the new order, and the responses of the tribal communities to the transformation in their lives that colonial rule wrought. While focusing on ecology, society, and politics, the scholar also pays due attention to intellectual history, presenting sharp analyses of the works of both European officials and Indian anthropologists on the tribals of Singhbhum.

There were six significant attributes that this young historian’s work displayed which I discuss below:

First, an authoritative command of the literature on Adivasis by previous writers, both well-known and obscure, whether on the tribes of Jharkhand or on the tribes of other parts of India;

Second, the ability to locate and use a wide range of primary sources. The thesis rested on a staggering amount of research in national, state and district archives, and in obscure essays and books published more than a century ago;

Third, the willingness to acquire supplementary knowledge by fieldwork in the region under study. The young scholar seemed to have taken to heart the dictum of the great French historian, Marc Bloch, that a historian needs thicker boots as well as thicker notebooks;

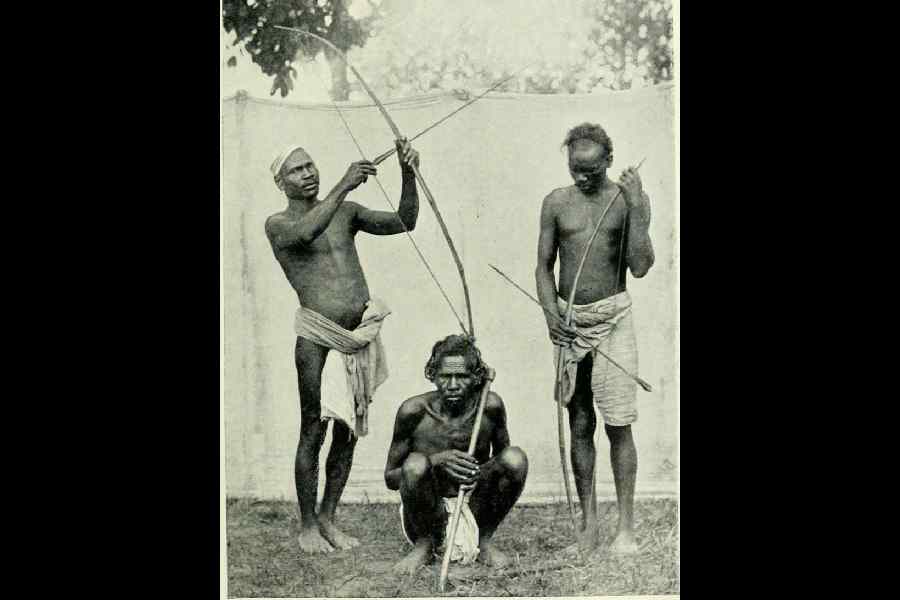

Fourth, an eye for vivid quotations from primary sources to illustrate his arguments. This, for example, is a British official in the 19th century writing about a hunt in the forests, and presenting a colourful picture of an apparently always unchanging tribal life: “Here are the ever dancing and singing Sontals, dressed out in flowers and feathers, with flutes ornamented with streamers made of pith, the wild Kurrias, or hill men, from the Luckisinnee hills in Borahbhoom; the Koormies, Taunties, Soondees, Gwallas, Bhoomijes&c, with sonorous ‘dammas’ or kettle drums, and other uncouth music, armed with swords, bulwas, and bows and arrows of every description; the Hos, simple and unpretending, but with the heaviest game bags…”

Another quote, from a century later and sourced from a file in the archives, has a participant in the Non-Cooperation Movement of the 1920s, saying (in translation): “Swaraj has now been attained and Gandhi is head of it. The English are leaving the country and the few Englishmen in Chaibasa would run away in three or four months time… No rents would be paid. Gandhi Mahatma would establish a school and the schools of Government would be destroyed. No fees would be paid in Gandhi’s school”;

Fifth, the ability to write up his material in clear and often compelling prose, with little academic jargon;

Sixth, a nuanced and subtle elaboration of his arguments. The scholar was particularly careful not to reproduce the stereotypes of tribal life common to colonial officials and contemporary activists. He presents a thoughtful critique of writings that present a straight line between tribal protests in the colonial era and in the present, “as having been prompted by the modern state’s disturbance of the previously idyllic custom based world of the adivasis”. The scholar speaks of how these writings are guilty of “essentialising adivasis as homogeneous communities operating through age-old and unchanging customs and traditions”. His own research, on the other hand, shows that “while many Adivasis resist the incursions of the state”, other “sections of them also collaborate with it; some also negotiate to enhance their standing vis-à-vis others in their communities”.

However, this thesis was not without its faults. The scholar had overlooked some crucial secondary sources that bear directly on his work, such as the writings of T.N. Madan on the history of Indian anthropology. I wished he had made more use of folklore and oral history. And not all the quotes from primary sources were as telling as the ones I have highlighted in this column. Some were far too long and diluted the narrative.

Nonetheless, this was one of the most accomplished doctoral dissertations by an Indian that I have read. Normally a thesis of this quality is published as a book a few years down the line, its flaws ironed out by a good editor. If one looks at comparable works in this field of environmental/social history, such as Nandini Sundar’s Subalterns and Sovereigns and Mahesh Rangarajan’s Fencing the Forest, they both saw a gap of merely a few years between thesis submission and book publication. The same sort of time lag has been witnessed for more recent historical monographs, by, among others, Bhavani Raman, Aditya Balasubramanian, Nikhil Menon, and Dinyar Patel, all of which started out as doctoral dissertations.

These books have been widely read and admired. I have no question that the thesis I just read would likewise be widely appreciated when it is published as a book. Tragically, although the thesis was submitted in 2018, it hasn’t still appeared in book form. This is because the scholar’s name is Umar Khalid. A cruel and punitive State, coupled with a tardy judicial system, has — at the time of writing this column — kept this talented historian in prison for more than five years, without bail, and without even formal charges being filed.

I have never met or spoken with Dr Umar Khalid myself. However, on one day in December 2019, we both took part in a peaceful countrywide protest against a discriminatory law, he in Delhi and I in Bengaluru. In the years since, I have sometimes wondered at the different paths our lives have taken, and the reasons for this. Have I been able to carry on my research and writing, whereas he has not, because my first name is Ramachandra and not Umar?

I have written about Dr Khalid here because, as a historian of modern India myself, I am in a position to appreciate the depth and richness of his scholarly work. But as I close this column, I must note that he is one of many fine, upright men and women, who are languishing in jail under dubious charges hastily filed by the police under orders from their political masters. Some of these Indians are also scholars and researchers. Others are social workers and civil society activists, who have in their life and work shown themselves to be steadfastly committed to non-violence and the founding values of the Indian Constitution. It is this commitment to pluralism and democracy, and perhaps nothing else, that has made them fall foul of the authoritarian and majoritarian tendencies of the ruling regime. So these remarkable young compatriots of ours have come to spend their best years in dark, dingy, and insalubrious prisons, when they could be contributing so much to the life of our Republic. It is surely past time that our judges find the decency and the courage to deliver the freedom that is currently denied to them all.

ramachandraguha@gmail.com