It was nearly half a century ago when my grandfather first showed me his treasured collection of old postcards. The battered, olive-green album was almost as old as the cards themselves, dating from the first decades of the twentieth century. Yet something about the pictures on those yellowing postcards caught my boyish fancy and I have been hooked on them ever since.

While he had loved cards with Japanese paintings — cherry blossoms and pagodas — I have always felt more drawn to the old, hand-drawn cards produced in colonial Calcutta. Most of these artists produced several cards, usually sets of images around a particular theme. Hundreds, if not thousands, of these cards were printed using the new image-printing technologies. Among senders, receivers, friends, and eventually collectors, the numbers that savoured these pictures were even higher. Yet, ironically, we know next to nothing about these hugely popular artists.

The absence of any information about the artists along with their subjects — often ethnic ‘types’ — has led to such postcard art being sundrily dismissed as a series of racist stereotypes. Yet, even if one only sees stereotypes, who sees which stereotypes and how they visualise it still tell you a lot about who they were.

While several artists did indeed produce sets of ‘types’, the characters included in each set varied. One artist included a “Gharry Wala” or coachman in his set of “Calcutta Curiosities”; another depicted a “Sandwich Man”, namely, a man carrying a folded advertising board around his body; a third drew a Marwari businessman. Why did one artist choose one character and not another?

Who they were, where they lived, and what they did shaped the ways in which they depicted the people and the places around them. These elements also shaped their outlook more generally. In other words, artist biographies mattered.

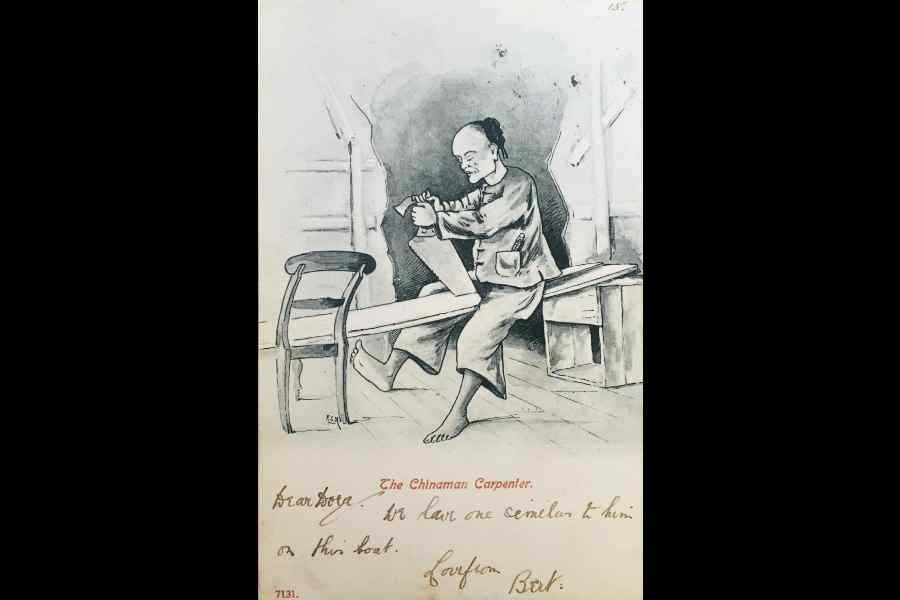

One card in particular had always made me wonder about the artist. It depicted an unusual subject — a Chinese carpenter. Chinese carpenters themselves were not surprising. But the choice to include them in a set of Calcutta ‘types’ was intriguing, even fascinating. In its own humble way, it captured the cosmopolitanism of the city in a way few visual artists of the day did. The card formed part of a set of over twenty cards. Some of these were available in both black-and-white and colour versions. Most of them, including the one depicting the Chinese carpenter, bore only a small, squiggled signature saying, “F.C.R.”. Only one card had a fuller signature — Fred C. Rogers.

Besides postcards, Fred C. Rogers also did a few other commercial illustrations. He did, for instance, some striking illustrations for early HMV catalogues around 1905. One of them depicted the emperor, Jahangir, listening to a gramophone! His earliest published work had appeared about two decades earlier. In 1884, he illustrated a curious little book published by Thomas McGuire of Calcutta. McGuire, who oversaw the local European poorhouse, was concerned that public charity was being leeched off by the undeserving. To discourage such misplaced benevolence, he penned a book on the “Professional Beggars” in Calcutta. In it, he provided a typology of various types of poor European impostors ranging from the “struggling author” needing money to publish his magnum opus to the “tearful mother” needing money to bury her dead child. Far from the imperial humbug of the colonial burra sahib, here was an encyclopedia of roguery exposing the unseemly underbelly of the imperial race. Moreover, the colonial classificatory eye, usually focused on Indian ‘tribes and castes’, was here turned back on British reprobates. It was these villains who came alive through Rogers’ sketches.

Frederick Burt Campbell Rogers’s life is almost as fascinating as his art. Born on April 5, 1848 on the Isle of Man, he and his brothers were enrolled at Rev Dr Emerton’s Hanwell College by 1861. Hanwell College specialised in preparing boys for careers in India. Sometime around 1870s, he came out to India with at least one of his brothers.

By the time he married in 1883, he was in his mid-thirties and working as a police officer at Goalundo. Notwithstanding its current obscurity, Goalundo was one of the most important inland river ports in the nineteenth century. Most of the traffic of goods and people moving from Calcutta to the eastern Bengali districts, or further still to the tea districts of Assam, had to go via Goalundo. It was a major travel hub.

Rogers’s bride, Norah Honor McGuire, was none other than the daughter of the aforementioned Thomas McGuire. The marriage seems to have paved the way for the couple to move to Calcutta. By 1885, when their son was born, he was working at the Administrator-General’s office in Calcutta. A decade later, when he baptised his daughters in 1896, his profession was listed as ‘artist’. It was unusual for a man in his forties to leave the stability of a government job and set up as a full-time artist. He was clearly passionate about art; he even named one of his sons Thomas Landseer, after the famous British engraver. Notably, the period between 1890 and 1918 is usually called the Golden Age of picture postcards. Rogers was thus one of the first local artists to see the potential in these humble cards.

What interests me is the way his own biography shaped the imagery. The Chinese carpenters, for example, were known to work on the large steamers travelling east. They were thus a common sight in Goalundo, much more noticeable than they were in Calcutta. His “Inland Serang” depicted the boatswains who skilfully navigated steamers up the treacherous Padma and the Brahmaputra. The “Sandwich Man” card showed an advertisement for the Calcutta Phototype Co., a subsidiary of the famous publisher, Thacker, Spink, & Co., and pioneers of local picture-postcard production.

Even when depicting labouring Asian men and women as ‘types’, Rogers managed to invest them with a dignity and individuality that were rare for colonial-era artists. The young Serang and the old postman acquired a certain quiet dignity in his hands. Nowhere is this clearer than in his portrayal of the ayah. A stock figure of colonial imagery, like most colonial images of the feminine, ayahs tended to be objectified as coy, young women forever available to the gawking eye. But Rogers, remarkably, portrayed her with her back turned to the viewer. While colonial images of ayahs are aplenty, I have never seen another one with her back turned to the viewer. It admirably captures how Fred Rogers managed to, quite literally, take colonial stereotypes and turn his back on them.

Public tastes have always been vulnerable to historical changes. After the Great War, collotypes were replaced by halftones and real-photo postcards and new themes displaced older ‘type’ sets. In these vicissitudes of time and taste, Rogers’s bold pictures lost their appeal and by 1928 he was officially declared an insolvent. As photocards depicting buildings, statues, and occupations slowly pushed out the hand-painted ‘types’, all that remained to bear testaments to one man’s passionate artistic experiments in a colonial society trapped in its own stereotypes were a handful of yellowing cards in tattered old albums.

The author wishes to express his deepest gratitude to Fenella Walter for her help in researching Fred Rogers’s life

Projit Bihari Mukharji is the Head of the History Department at Ashoka University. He researches the history of science and collects old postcards