By a fortunate coincidence, this column appears on the seventy-fifth birthday of the living cricketer I hold in the highest esteem. I admire him for his achievements on the field, and, perhaps even more, for how he has conducted himself off it. He is that rare example of a great cricketer who is also a very fine human being.

Oddly enough, one of my first cricketing memories of Bishan Singh Bedi has him with bat, rather than ball, in hand. In the Delhi Test of 1969 against Australia, Bedi was sent in as nightwatchman on the fourth day, and safely saw us through till stumps. The following morning, he batted for an hour and a half with Ajit Wadekar, building the foundations for a famous victory, every ball and every run followed by me (and millions of others) on All India Radio.

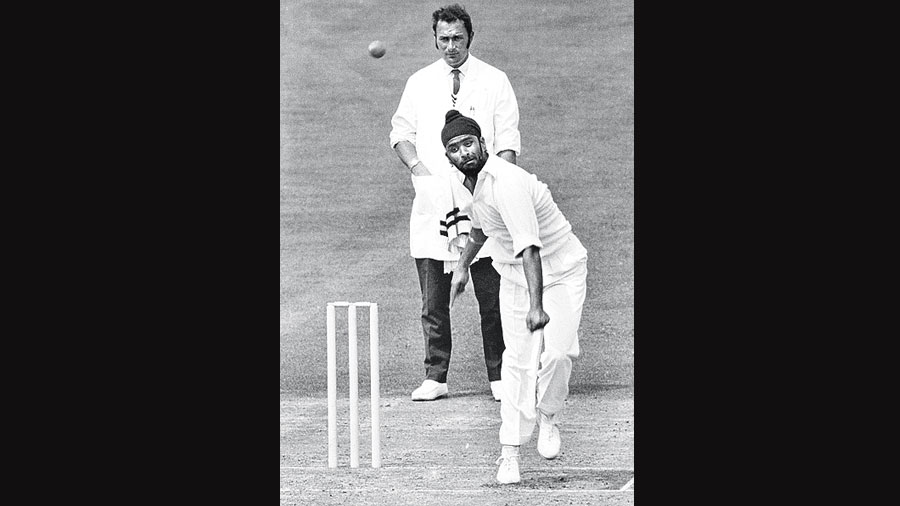

But of course it is as a great spin bowler that Bishan Bedi made his mark on cricketing history. I myself watched Bedi bowl often, in Test cricket and in Ranji Trophy cricket, and never tired of the sight. I remember him lovingly for his classically perfect action, for his masterly control, for his powers of flight and spin, and for his ability to get the better, on all wickets, of the finest batsmen in the world.

Bedi’s life in cricket has been celebrated in a volume published on the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday. Titled The Sardar of Spin, it brings together tributes to Bedi by cricketers of his generation who played with or against him, by writers who followed his career (full disclosure: I am one of the contributors), and by cricketers of younger generations who were mentored or inspired by him. The book is the brainchild of the former Delhi opener, Venkat Sundaram, who played under Bishan Bedi in the Ranji Trophy for many years and remembers with particular fondness the first time Delhi won the championship, in 1978-79, when he was one of the players and Bedi the team’s inspirational captain. It was Venkat Sundaram who conceived of the book, who brought together an array of contributors from around the world, who sourced the photographs, and who found a publisher. It is a mark of the man’s self-effacement and innate decency that his name does not appear on the cover.

I warmly commend The Sardar of Spin to lovers of cricket (and not just Indian cricket). In my first reading of the book, I was myself particularly moved by the contributions from those foreign cricketers whom Bedi played against, such as Greg Chappell and Mike Brearley, and by the tributes offered by Indian spin bowlers whom Bedi mentored and inspired, such as Murali Kartik and Anil Kumble. Also insightful are the essays by journalists such as Suresh Menon and Clayton Murzello, who followed Bedi’s career as it unfolded.

Since my own essay in the book is about Bedi the bowler, in this column I wish to speak rather of Bedi the man. It is one of the sad truths about Indian cricket today that the greater the cricketer, the more opportunistic and spineless the human being. Cricketers with fame and wealth always seek to stay on the right side of the administrators of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, always curry favour with politicians, and never take a stand on matters of personal ethics or political principle. There are indeed a few Indian cricketers in their thirties and forties who occasionally speak out against discrimination on the field and in everyday life, but these are never those who have the most influence or authority.

In the entire history of Indian cricket, there have perhaps been only three individuals of whom it could be said that they were both great cricketers as well as human beings of character and principle. Chronologically, the first member of this trinity was Palwankar Baloo. Born in a Dalit home in 1875, he overcame the enormous barriers that culture and history placed upon him to become the first great Indian slow bowler, indeed — if we regard Ranjitsinhji as an English cricketer, as we should — the first great Indian cricketer itself. By his dignity and his bearing and his achievements on the field, Baloo inspired many younger Dalits, among them B.R. Ambedkar himself. After Baloo had taken more than a 100 wickets on the first All India tour of England in 1911, on his homecoming he was given a reception by the Depressed Classes of Bombay, at which the manpatra, or welcome address, was read out by the young Ambedkar in what was probably the first public appearance of one of the most influential Indians of modern times.

If Palwankar Baloo was the first great Indian bowler, then Vijay Merchant was surely the first great batsman nurtured on Indian soil. Born to privilege, the child of a prosperous industrialist, unlike most rich brats, Merchant retained his scruples and his principles. Chosen for the 1932 tour of England, he dropped out because Mahatma Gandhi and other nationalists were in jail. Later, as a player, he financially helped the families of Indian Test cricketers who died young, such as those of his teammates, Amar Singh and Sadashiv Shinde. Still later, in retirement, he worked for the rights of children with special needs, and helped found the National Society for Equal Opportunities for the Physically Handicapped.

Baloo and Merchant were towering figures in the history of Indian sport who never allowed their cricketing fame to pervert or corrupt their characters. Bedi is, to my mind, the third — and probably the last — great Indian cricketer to be an exceptionally courageous human being as well. In his playing days, he campaigned tirelessly for the rights of players and against the conniving ways of our administrators, for which he paid a price. After retirement, he eschewed lucrative commentary contracts to nurture and mentor young cricketers in the coaching camps he ran. As captain of Delhi, he made a group of untried youngsters the fulcrum of a Ranji Trophy-winning side; as coach of Punjab he did the same. Whether active or retired, he has always put the game above himself.

Bishan Bedi has both an acute understanding of Indian society and a strong moral compass. My own admiration for him rests only partly on what he did as a cricketer; it owes itself equally to what he has taught me about life and human conduct in the years I have been privileged to count him as a friend.

Born on September 25, 1946, Bishan Bedi grew up with and has grown old in a free India. Last year, on the occasion of Independence Day, he wrote a moving article in The Indian Express on the crises our country has witnessed in his lifetime, and how he has faced them. He spoke here of our wars with Pakistan, of the anti-Sikh riots, and, most recently, of the sufferings that the pandemic has wrought. Of the “heartbreaking images” that the prime minister’s unplanned lockdown produced, Bedi wrote: “It highlights the utter lack of compassion in our politicians, who enforced the sudden and complete lockdown. Honesty and transparency, too, are missing when it comes to coronavirus numbers.”

Reflecting on a nation whose journey has been more or less coterminous with his own life, Bedi remarked that “the one thing that has really pulled this nation down is sycophancy. I have experienced this in the past and now I see it all the time.” He deplored the fact that “even the young and the educated are joining the political conundrum and are reluctant to raise their voice. The reason: sycophancy.”

The last paragraph of Bedi’s article ran: “I, fortunately, had the gumption and the strength of character. When I was young, and so was India, I was able to stand up and be counted. Now, it is too late in life. But I am not a pessimist, I have faith in my spirituality and I have hope. We survived wars and invasions and we will survive the political pandemic, too.”

If Tendulkar or Gavaskar or Kohli or Dhoni or Ganguly had half the strength of character that Bishan Bedi has, Indian cricket would be run in a more democratic and transparent manner, be more accountable to all its stakeholders, and not be so cravenly sycophantic to the political class. However, individuals like Bedi are scarce not just in Indian cricket; they are scarce in Indian politics and public life too. That is the greater tragedy of our Republic.

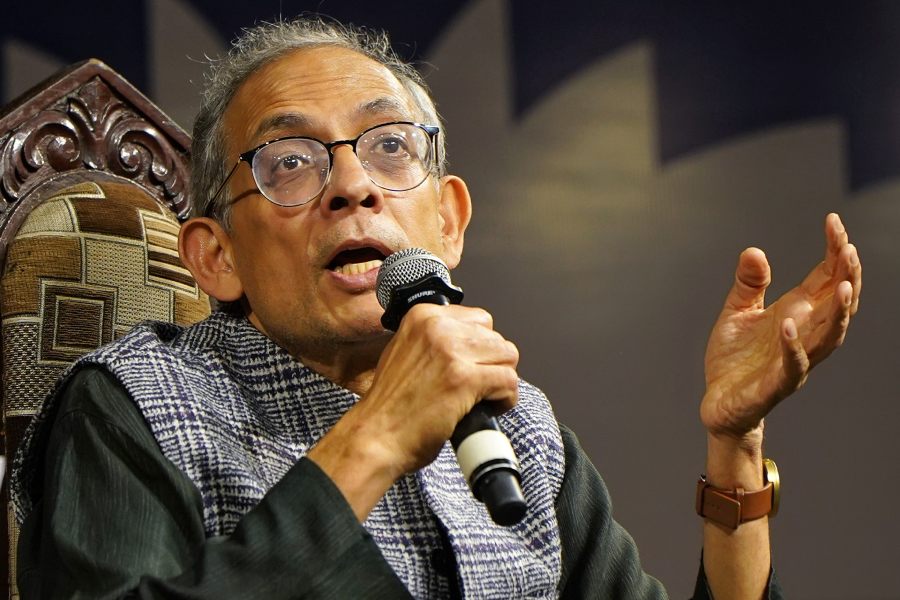

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in