Literature is a landscape that mirrors reality. It is not surprising then that a new study published in Earth has found that people’s connection to nature has declined by more than 60% since 1800, mirroring the disappearance of words referring to the natural world, such as ‘river’, ‘moss’ and ‘blossom’, from books in English around that time. The study goes on to show that the words used in English-language books written in the last 200 years reflect life, which, since the Industrial Revolution, has moved indoors. The fall in literary references to ‘meadow’ thus corresponds to the rise of ‘factory’, the shrinking of ‘river’ echoes the growth of ‘cities’ — linguistically and literally. This erosion of the natural in English language is borne out by other examples. The Oxford Junior Dictionary, for instance, removed words like ‘acorn’, ‘kingfisher’, and ‘willow’ in favour of ‘broadband’ and ‘chatroom’ recently. When a language loses its words for the living world, it is not just the lexicon that shrinks; imagination does too. For instance, psychologists at the London Business School found that without the word, meadow, a child cannot easily picture its soft, green expanse; without the word, bough, the branch becomes just a stick.

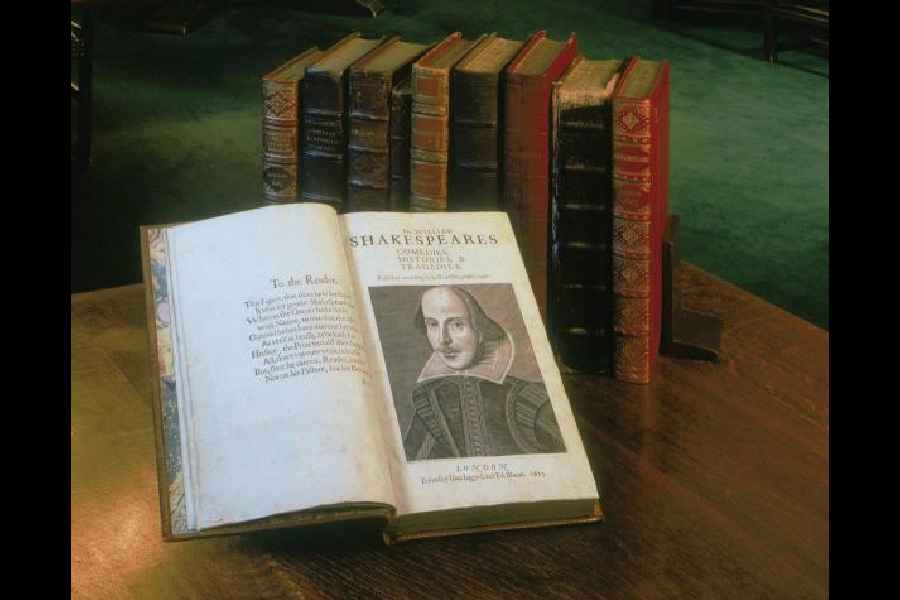

For centuries, English literature served as a record of ecological intimacy. William Shakespeare used the natural world to capture human emotion — a tempest could stand for rage, a summer’s day for love, a wilting rose for mortality. Wordsworth went further, trusting the natural world more than human institutions. “Come forth into the light of things,” he urged, “Let Nature be your teacher.” Thomas Hardy, writing much later, caught the moment when that world began to collapse. His Dorset landscapes throb with rivers and heaths, but modernity had already begun to gnaw at their edges. His novels hold the ache of that transition — the sense of a people losing not only their land but the words that named it.

One of the cultural responses to such a loss has, in recent times, been the rise of ‘cli-fi’ — climate fiction that imagines the apocalyptic outcome of the loss of nature. From Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to Sarah Hall’s The Carhullan Army to Amitav Ghosh’s non-fiction writing, writers are increasingly chronicling landscapes of desolation and warning. This is a depiction of sterility that is also eroding language and literature which are, in turn, losing words associated with nature.

The next frontier should perhaps be desire, not dystopia. What literature needs now is not only climate fiction but nature fiction — stories where the natural world is portrayed as something to crave, protect, and celebrate. Books where rivers still sing and forests are characters, not casualties. Writers such as Richard Powers (The Overstory) and Barbara Kingsolver (Flight Behaviour) have shown that ecological storytelling can move readers as deeply, that trees, bees, and the wind are not just metaphors but kin. This rewilding of language may be as vital as the rewilding of land. Can the revival of nature in word be matched by deed? That is not certain. But without it, no policy or technology will matter because to protect something, one must first remember its name.