On a buzzing stretch of Raja Rammohan Roy Road in Behala, between vegetable vendors, and scurrying autos and rickshaws, is a small paan shop that’s anything but ordinary. From this unassuming stall, 47-year-old Pintu Pohan has authored over a dozen Bengali books. Between the smell of freshly cut betel leaves and the application of choon on them, he has been building a parallel world of words and dreams.

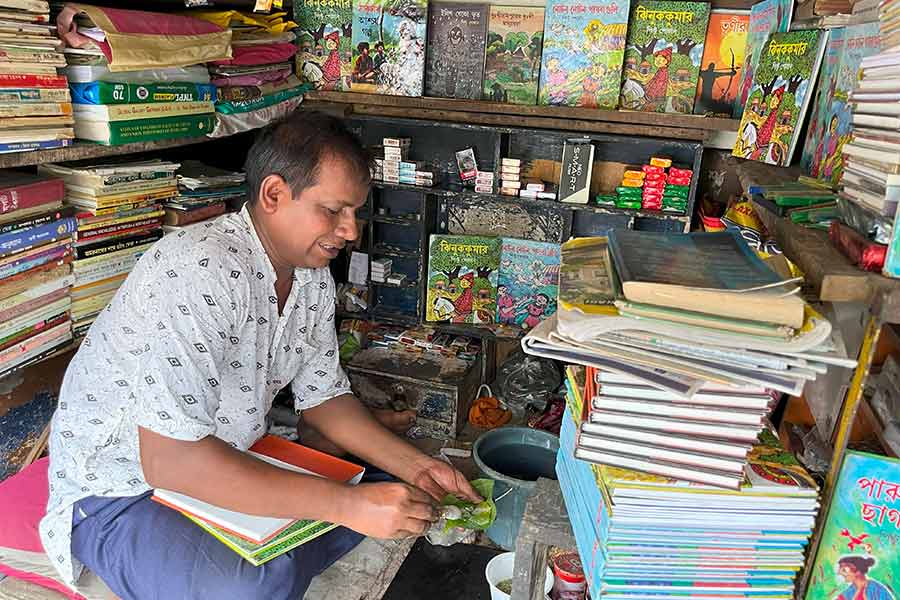

Pohan’s life is a testament to unyielding hope. “When you want to do something, you will do it anyway. It is difficult to sit here and write, amidst the bazaar and the busy road. But I have done it all from here. Be it completing my higher education or writing my books — everything has been shaped in this small shop,” he said, gently folding a betel leaf.

A childhood framed by struggle

Pohan prepares a paan

Pohan grew up in Madanmohantala, about 2km from Behala’s Chowrasta, at a time when the area was mostly swamp. His family’s hardships shaped his early years. “We can live only by fighting. Those who live below the poverty line, those who have families and responsibilities, have to fight every day to survive,” he said.

He was a good student in school, winning local competitions and dreaming of a better future. But poverty clipped his wings. “I didn’t know what would happen to me in the morning. I would often go to sleep not knowing if I’d have food the next day,” he recalled.

When he was forced to drop out after Class X, he did not surrender. He worked as a helper, a factory worker, anything that brought in a little earnings. Eventually, he returned to school, completed his graduation, and went on to do a Master’s in Bengali in 2015. “I did it all with my own money, my own savings. I didn’t know how I would manage it, but I kept going,” he said.

Writing, from the cracks of daily life

'My sustenance is the people around me. This world, to know it, to understand it. That is what feeds me. Books gave me a life ticket to a different world,' says Pohan

Pohan’s writing began as a child. Song lyrics scribbled on scraps of paper, poems published in school magazines. But the real journey began much later when he was in his 30s, as he sat behind the counter of his shop, listening to the world go by and carving his own.

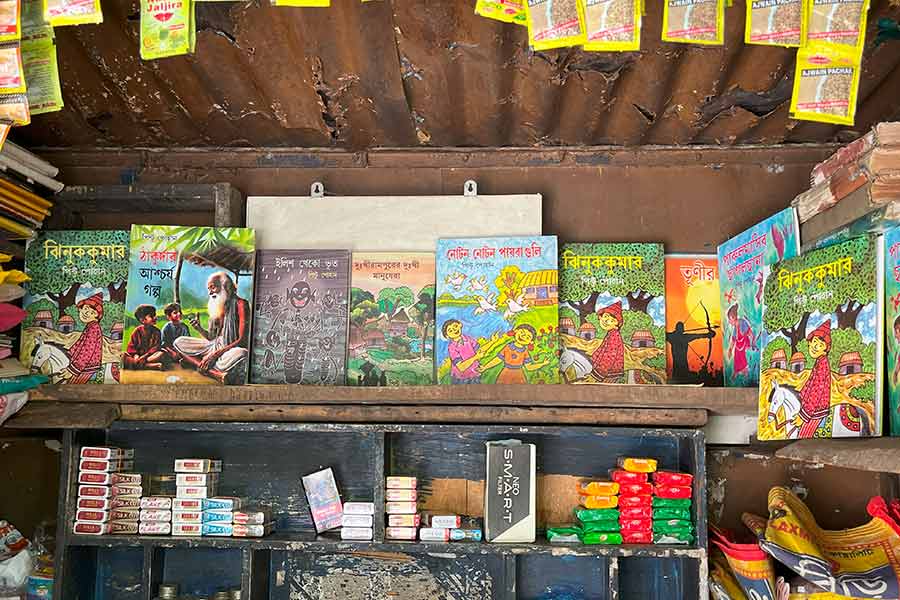

“My sustenance is the people around me. This world, to know it, to understand it. That is what feeds me. Books gave me a life ticket to a different world,” he said. Some of his works include Parul Mashir Chhagol Chhana, Jhinukkumar, Thakurdar Aschorjyo Golpo and more. His stories have been published in renowned magazines like Sananda, Desh, Anandamela, and more. “I never imagined my name would be published in all these magazines. But I kept writing, and slowly it started happening,” he said.

Between paan, poetry, and pain

Pohan shows some of his books

The journey has not been easy. Long hours at the shop led to severe health issues. “The doctor told me I had Lumbar Spondylitis and Cervical Spondylitis. They said I should rest for six months. But how could I? I had responsibilities. I had dreams.”

Pohan juggled shop hours with courses. From computer basics to language diplomas in English and Hindi, he has always been trying to add more to his arsenal. “I didn’t even know how to type. I would go to a shop to learn operating a computer, then rush back to sell paan,” he said.

Still, he kept writing. “Writing was in me since the beginning. I knew I wanted to write something meaningful, something lasting.”

Dreams, on a paper-wrapped leaf

Pohan tells stories that resonate with children and adults alike

Despite everything — poverty, pain, long hours, failed jobs, unpaid wages, and police harassment — Pintu never gave up. He simply moved forward. “I used to work from 6am in the morning till midnight. Today I earn enough to feed my family and fund my books,” he said, without complaint.

His family comprises his wife, a school-going son, and a college-going daughter. “I never wanted to just fill my stomach with rice and fish. I wanted to fill it with meaning,” he explained.

In his latest works, he continues to tell stories that resonate with children and adults alike. “I want to show the way to other people like me — the children who don’t know if there’s a tomorrow, the people who are scared to dream.”

Fighting the darkness with words

“Being poor is not a crime. The real crime is giving up on life, giving up on dreams. My life has been built sitting in this shop. And if someone asks me what I have learned, I will say this — it is not bad to not reach your goal. But it is bad to stop fighting. I have lost a thousand times. But I still want to fight,” he concluded, handing over another paan to a customer and a book to another.