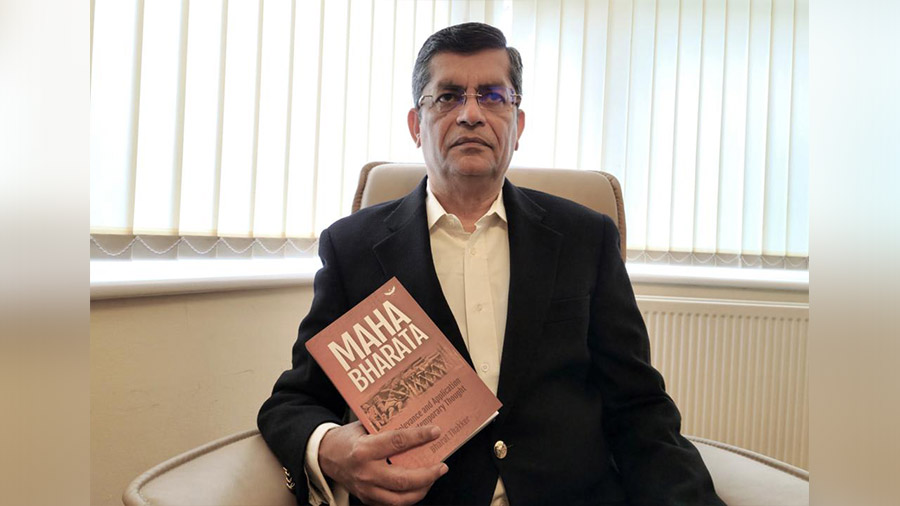

The Mahabharat isn’t just a story of familial rivalry. It mirrors and moulds society. It shows us who we are and directs us towards who we can be. Bharat Thakker, a finance consultant turned author, spent eight years researching the epic, layer by layer, finally compiling all his learnings in his new book, Mahabharata: Relevance and Application in Contemporary Thought (Garuda Prakashan). During a Zoom interview with My Kolkata from his London home, Thakker walked us through his process, explaining his deconstruction of one of the greatest stories ever told.

An epic journey

Born in Kolkata in 1957, Thakker spent his formative years studying at St. Xavier’s Collegiate School. It was here that he was first introduced to the Mahabharat, surprisingly in a language that wasn’t his mother tongue: “We used to study Bengali as our third language in school. To help us learn the language, we were prescribed children’s editions of the Ramayan and Mahabharat.”

While pursuing a BCom degree at St. Xavier’s College, and, later, while preparing for his chartered accountancy examinations, Thakker rarely gave the epic much thought. But all that changed when B.R. Chopra’s landmark series, Mahabharat, first began to air on Doordarshan in 1988. “What I had studied in school suddenly came back to me in the form of this brilliant show, and it rekindled my interest.”

It was in Kolkata that Thakker began building his career in finance, but in 1997, he left for London. After setting up an international business division for an Indian conglomerate, he found success in two disparate industries — telecom and steel. Eventually, he branched out into consulting. Working with several Indian business houses, he travelled to Hong Kong, Dubai and Saudi Arabia. Seeing that his consulting duties were leaving him with a little more time to read, Thakker was again drawn to the Mahabharat. “Around 2005 and 2006, I was looking up the Indian epics and I casually picked up a book on the Bhagavad Gita, which constitutes 700 of the Mahabharat’s 100,000 verses. I began to wonder, if these 700 verses are so amazing and have interested people for generations, what lies in the entire 100,000?”

‘What I had studied in school suddenly came back to me in the form of this brilliant show, and it rekindled my interest,’ says Thakker of B.R. Chopra’s landmark series, ‘Mahabharat’, which first aired on Doordarshan in 1988

As he dug deeper, he discovered that there were many versions of the epic, orally passed down by different people from different parts of India. “The uniqueness of these versions led me to go from ‘what is there’ to ‘what is where’. As I began researching, I realised that the market had plenty of books. In some, a writer had rewritten the epic in their own words. In others, they had fictionalised a particular character. A lot of people had written their interpretation of the Gita’s 700 verses, but there was still a big vacuum. I felt the Mahabharat needed to be interpreted as a whole. I thought, ‘Why not take my research a step forward?’, and ask, ‘Why is it there?’”

Thakker’s vision was clear. He wanted to explore the universal relevance and teachings that the Gita imparted, but in the context of the entire Mahabharat. “The Gita begins when Krishna reveals the ultimate destination and desire of the soul to Arjun. It’s the most motivational image, but how does one get there? I believe that the Mahabharat acts like an atlas through which a ship can navigate its way to the lighthouse, which is the Gita. This became the centre of my research.”

Thakker believes his book doesn’t need his readers to have prior knowledge of the epic. The book begins with an introduction to Hinduism. Each chapter starts with an event from the epic, followed by its interpretation. For Thakker, his corporate background was instrumental. Not only did it help him derive his interpretations, it also helped him make his book relevant. “My work was not only about finance; it also involved the managing of businesses and people. Many of my life lessons came from interacting with young people and also people of my age. I have used all my learnings to explain how particular events from the Mahabharat can be relevant to our lives. One can apply these learnings to their personal life, business life, or even their relationships.”

‘I believe that the Mahabharat acts like an atlas through which a ship can navigate its way to the lighthouse that is the Gita. This became the centre of my research,’ says Thakker

Old stories, new meanings

In Thakker’s view, the Mahabharat can shape our understanding of the modern world. Using Dronacharya as pivot, Thakker discusses intellectual property: “You can consider Dronacharya’s teachings as his intellectual property. He had the absolute right to impart it to whoever he wanted. When Drona found that Ekalavya was copying his lessons without consent, he asked for his thumb as gurudakshina, disabling him from ever stringing a bow.” Another dimension of intellectual property is how the owner can use it for his benefit, says Thakker. “Drona’s decision to make Hastinapur’s princes capture Dhrupad as gurudakshina falls in line with the law, where a person giving the intellectual property has absolute right over it till his payment is discharged. It can be tweaked to the contemporary context to show how people working for a software company do not own the software they develop; it belongs to the company.”

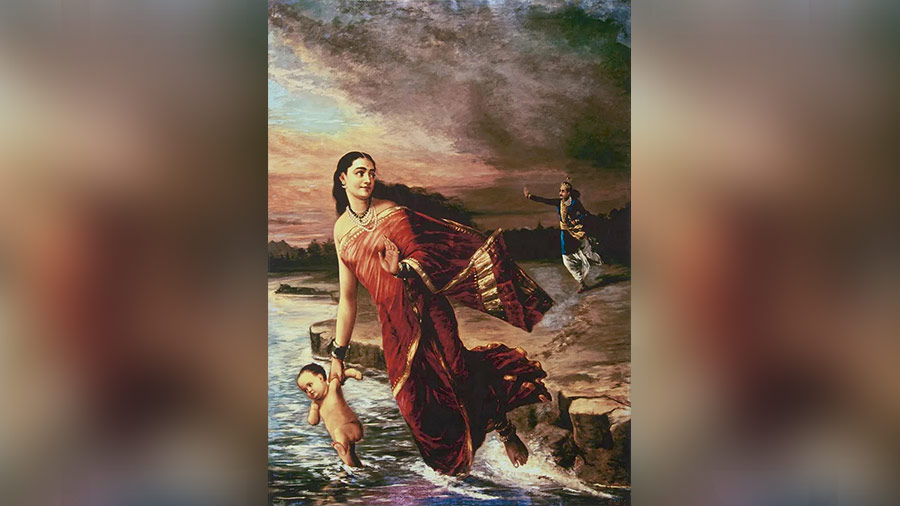

Taking us back to the start of the epic, Thakker argues that the Mahabharat lays a foundation for Indian society. He talks of how Shantanu marries Ganga, promising to never question her judgement. He holds his silence when she drowns their seven sons, but questions her when she attempts to drown the eighth. Ganga then leaves with the child. She raises him single-handedly, returning him to Shantanu only after he has finished his education. “The story of Bhishma’s birth tells you that if a promise is breached, you can end the contract – the contract here is of marriage, and its breach leads to divorce. There is also a reflection here on child custody. The story implies that the upbringing of the child should be with the mother, where he gets his sanskar (values), while he should receive his varna (caste) from his father.”

Shantanu stops Ganga from drowning their eighth child, in this painting by Raja Ravi Varma Wikimedia Commons

Like with its beginning, Thakker also attributes a profound underlying meaning to the Mahabharat’s end. Analysing the order of the Pandavas’ death, he says, “Sahadev is the first to die among the brothers, signalling the death of our perspective and ability to see the future. Nakul, regarded as the handsome one, dies next, signalling the lesser interest one has towards their wellbeing and looks after their emotional attachments wane.” Once the Arjun in us gives in, we die from within and lose our sense of purpose and direction, says Thakker. Our self-abuse then reflects on our body, giving away its strength, Bhima. “When our brain or Yudhishthir finds no support from either our emotional or physical side, it stops working and we die.”

Women’s rights is another prominent theme in the epic. Kunti, a widow, isn’t cast away. She actively participates as the Queen Mother. Thakker, surprisingly, highlights female agency by bringing up the holy trinity of Hindu gods – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiv. “Brahma is associated with Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge or method. Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu, is the goddess of wealth or means, while Shakti, the consort of Lord Shiva, is the goddess of power or motivation. I believe that for human life to survive and grow, we need these three ‘Ms’.”

Somewhere over the rainbow

In his book’s 400 pages, Thakker has listed 200-odd insights that he has extracted from the epic’s events. “I consider the Mahabharat to be like a rainbow made of several colours, with a transition of shades. Each individual shade is made up of several strands which have a relevance to our day-to-day lives. This is what I have tried to show in my book.”

‘People are not bad per se, even if some of their actions may not be acceptable to you. You have to judge a person’s action in isolation, in its context, rather than make a general judgement,’ says Thakker Shutterstock

For Thakker, the Mahabharat’s greatest lesson is that not everything is a binary. “Things don’t have to be black or white, right or wrong. People are not bad per se, even if some of their actions may not be acceptable to you. You have to judge a person’s action in isolation, in its context, rather than make a general judgement. My objective is not to say that the Pandavas were good or the Kauravas were bad.” It is this objectivity that allows Thakker to see the epic as a commentary on universal themes that oftentimes exceed faith: “The Mahabharat came into being over 5,000 years ago, when none of the modern religions existed. I talk about the Hindu way of life without siding with any one path to moksha, and without challenging any faith.”

Thakker’s eight-year-long research and writing process, he says, has left him transformed. “The central theme of the Mahabharat is dharma, which represents duty, responsibility and obligation. It is not just about what we do for ourselves, but also what we do for our family and the world around us. My research has left me more measured in everything I do and say. I feel calmer in my thoughts, too. I see life in a more rational and realistic way, beyond my emotional response.”

The author believes that anyone can use the epic to achieve this, and more: “I want my book to help people validate their beliefs with rationale, and not use fear as a way for action. I want to emphasise on how life is not about a choice between two binaries. We typically believe that the tossing of a coin results in either heads or tails, but once in 6,000 times, the coin can land on the third side, the edge. Even for simple things, I want to reveal that third option.”

Mahabharata: Relevance and Application in Contemporary Thought by Bharat Thakker is available online with Amazon, Flipkart and Garuda Books.