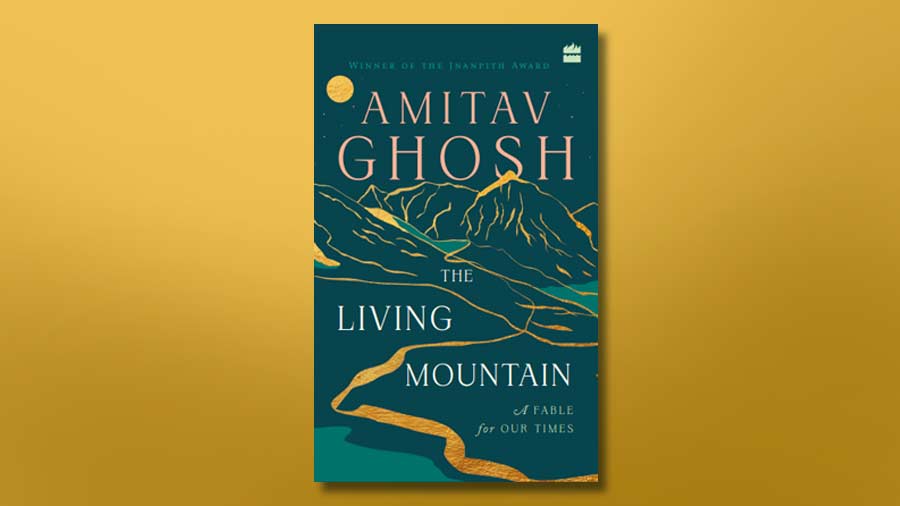

Author Amitav Ghosh’s new book, The Living Mountain, A Fable for Our Times, is a cautionary tale that presents possibly the gravest predicament humankind has ever faced — the climate crisis. A global literary figure and the first English-language author to receive the Jnanpith Award, India’s highest literary accolade, in 2018, Ghosh has been vocal about climate change for a long time. My Kolkata caught up with him at his Jodhpur Park residence about his new book, climate change, climate engineering and the catastrophe waiting to happen because of human greed.

Writer Amitav Ghosh at his Jodhpur Park home Amit Datta/ My Kolkata

My Kolkata: You have been writing about climate change for a long time now. Even as you wrote, one catastrophe after another unfolded across the world. Do you sometimes feel like a seer who would love to be proved wrong?

Amitav Ghosh: (Smiles) Yes, of course. You know, what is happening, nobody would want to see or predict. But, I suppose, I really became interested in climate change when I was doing the research for my book, The Hungry Tide. That’s set in the Sunderbans. I have been going to the Sunderbans since I was a child. But seeing it at that particular point in time, it was already very clear that there was something really weird happening. Because islands were drowning and many kinds of species were disappearing.

I remember before, when we went to the Sunderbans, the mudflats at certain times would turn red with crabs. And the crabs are the keystone species of a mangrove forest. They are the ones who keep the forest alive. You don’t see that any more in the Sunderbans — just banks covered with crabs.

If you look at the birdlife, it’s so diminished. It was clear from just talking to people there that massive changes were under way. (Also) saltwater intrusion — all of these things were happening. And then, I think, for the Sunderbans, one of the key events was Cyclone Aila. Cyclone Aila impacted the Sunderbans very, very badly and it has not really recovered since. It has been a downward spiral since then. So, when Cyclone Aila happened, I began to get a dreadful sense of urgency. It was clear that something absolutely catastrophic was unfolding. Since then things have only got worse.

As you know, every year, there are these catastrophic cyclones that reach deeper and deeper. Amphan can be cited as a good example of this phenomenon. The cyclone almost hit Kolkata. In the past, the Sunderbans had always protected Kolkata. Even in this case it did protect to some extent. But with the mangroves disappearing at such a pace, it’s actually the whole interior of Bengal that becomes incredibly vulnerable. I suppose it’s because I am a Bangali — how should I say — we have sort of an inherited knowledge of the extreme fragility of the environment. This issue has really sort of taken hold of me for a long time.

The cover of Ghosh's new book 'The Living Mountain, A Fable for Our Times'

I have read that you were supposed to write a piece for a non-fiction anthology and you wrote The Living Mountain…. Do you feel stories on climate will appeal to people more than essays?

No, I think non-fiction is good. I have written a lot of non-fiction on these issues. The Cambridge University Press is publishing a collection of essays on understanding the Anthropocene [an unofficial unit of geologic time used to describe humanity’s impact on Earth]. They got all the top experts from around the world. They also wrote to me saying they would like me to write. They had a very tight limit of 5,000 words. I thought to myself I could never say what I wanted to in the form of an essay. I have to find some other way. I said everything I wanted to about the Anthropocene in this rather short story. In fact, Sukanta Da (literary scholar and academic Sukanta Chaudhuri) just emailed me. He wants to translate it into Bangla, which is such a privilege for me.

'Manasamangal Kabya' is in many ways very much an environmental story

Amitav Ghosh

Your latest book, The Living Mountain, is a fable. Earlier, Jungle Nama was your first book in verse. What has inspired you to explore these genres for your fiction?

Good question. You know, I wrote a book called The Great Derangement which explores the whole question of artistic forms — literary forms in relation to our present planetary crisis — and the argument I make there is that the novel as a form in many ways is impermeable to climate change. It cannot really deal with climate change in very easy ways. And I said over there it has become necessary for writers to try and experiment with other forms. After I finished writing The Great Derangement, I followed my own advice and started reading other forms (of literature). When I say other forms, I mean, literally, I wanted to read in different languages and so on. Because I read Bangla I started reading the whole Mangal-Kabya literature, especially Manasamangal Kabya. That had a really powerful effect on me because the Manasamangal Kabya is in many ways very much an environmental story. Manasa Debi actually represents in that kabya all the other beings of the forest. So, basically, the fundamental story from Manasamangal Kabya really completely captures the reality of climate change. Because Chand Sadagar is the merchant, he is there for profit, and Manasa Debi is the one who is restraining him. She speaks for the other beings, like snakes, but she also speaks for the weather.

In a way, Manasamangal Kabya presents a much more realistic picture of Bengal, of the environment of Bengal, than anything you would read today. So, that had a profound impact on me and I started to think about other ways to write. As you know, Manasamangal Kabya is written in Poyar (meter). So I wanted to write in Poyar. And, of course, I was familiar with the legend of Bon Bibi. I decided to adopt the legend of Bon Bibi and do something else but in verse. So I made a version of Poyar in English and collaborated with… artists like Salman Toor (for the artwork). Salman has now become one of the famous artists in the world. His works are selling and setting records. He has had major shows at The Whitney, New York.

A heatwave is a perfect example of what a certain critic calls ‘slow violence’, and that is so hard to capture

Amitav Ghosh

You have written that to fictionalise the reality of climate change one has to capture the stark uncanny of it all. But in doing so, particularly, in climate fiction movies, we see that they turn out to be a spectacle. So, how does one manage to bridge this gap and find a middle ground?

It is very hard, you know. As I said, the way that fiction is set up, it’s difficult to deal with events that are unusual or extraordinary. So I began the book, The Great Derangement, with something that happened to me as a student in Delhi. I was hit by a tornado at a time when nobody knew what tornadoes were. I tried to write about it in fiction and it was very difficult but it’s not impossible, you know. For example, I always think one of the beautifully structured works of art is Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali. One of the amazing things over there is how he uses the monsoon to divide his story into two halves….

These things are difficult because, essentially, the sort of crises we are facing now are not necessarily spectacular things. A tsunami is spectacular, a cyclone or tornadoes are spectacular. Consider what is happening in India right now, which is to say, a heatwave. How do you make heatwave a story? A heatwave is a perfect example of what a certain critic calls “slow violence”, and that is so hard to capture, the slow violence of these events.

Something like a cyclone or a tsunami is a sort of overwhelming thing that has pictorial elements. But sea-level rise on the other hand does not. The slow way the sea level rises has very concrete effects, and mostly in our part of the world, because the Sunderbans is actually quite heavily populated. For example, we talk a lot about the disappearance of the Pacific islands, which is a terrible catastrophe. But, say, a nation like Tuvalu, which is likely to disappear, has 10,000 inhabitants, whereas Bhola island in Bangladesh, which got half a foot submerged, displaced five lakh people.

So these are the ways in which these catastrophes are unfolding and we have not really begun to understand. One reason for that is the Indian media. I think one of the biggest stories of Bengal, Chhattisgarh and Odisha is the enormous outmigration that is happening. Say, for instance, in Goa, or anywhere down the west coast; today the working class is entirely from the east coast; mostly Bangali. I have seen this transformation literally in front of my eyes in the last 25 years. I had a house in a small village in Goa called Aldona. Years ago, I was the only Bangali there. Today, the entire working class of that place, like the people who paint houses, and even the Goan restaurants are run by Bangalis, all from these regions. So there is a huge outmigration happening. And for some reason, even The Telegraph does not seem to pay attention to this. I think it’s the biggest story in Bengal. Because it’s slow, invisible, nothing spectacular happens. But why is it that no one has written a book about this? No one is doing investigative journalism on this. In Bangalore now, there are schools where there are more Bangali-speaking children than Kannada-speaking children. This is an enormous demographic shift. And it really needs to be written about.

Geoengineering is one of the most dangerous technologies ever imagined

Amitav Ghosh

So these are the climate refugees or people who have been forced to migrate due to the climate crisis?

Yes, absolutely. I am a bit wary of the term climate refugee. I have talked to many, many refugees, not just here but also in Europe… in Italy. None of them would ever call themselves climate refugees. Because there are also many other things happening, [like] political conflicts and economic issues. But essentially they are [climate refugees]. They have been displaced by climate impacts. The Sunderbans now, already after Aila, the saltwater came so far in that it destroyed thousands of acres of cultivated land. Where are those people going to go? I do not know if you have seen the studies; apparently, the men go to work, but the women go to red-light districts in Kolkata. Or they become domestic workers and so on. This is a demographic catastrophe unfolding in front of our eyes and no one is paying attention to it.

Amit Datta/ My Kolkata

Technology has taken away our traditional way of coping with climate disruptions

Amitav Ghosh

As you said, many acres of land in the Sunderbans have turned barren due to the saltwater invasion. The government is trying to come up with saltwater resistant rice or paddy species. Climate engineering on a small scale has already begun. China is building sponge cities to combat flooding. Cloud seeding is being done all over the world to tackle droughts. What are your thoughts on this?

First of all, I would like to say that saltwater adapted species is not climate engineering in any sense. It is actually a process of adaptation and adaptability. [Ecologist] Debal Deb has been collecting these salt-resistant species for a long time. Historically also, saltwater intrusion often happened in the past. People who live in these coastal areas have always used salt-resistant species as a technique of adaptation. I think this is a very important thing. Unfortunately, these species were all on the point of loss when Debal babu began to collect them. I think he is one of the unsung heroes of the country. I try to support his work in every way I can. What he has done is really remarkable. He has conserved like tens of thousands of species which were all disappearing because of all these engineered varieties of rice. In the long run we have seen this Green Revolution has been a disaster. I think it is really sad that technology has taken away our traditional way of coping with climate disruptions. And I am sure this is going to happen more and more. Geoengineering is one of the most dangerous technologies ever imagined. Especially the kind of geoengineering they [advocates of climate engineering] are thinking of. They are thinking of injecting sulfuric acid in the outer atmosphere. What could go wrong with that!

The Living Mountain strongly critiques the colonialists and the urge of the once colonised to replicate their former master’s model of “development”. How far do you think colonialism has exacerbated climate change?

I think this thing [climate change] is entirely rooted in colonialism and capitalism. Colonialism creates the conditions under which certain kinds of capitalism flourish. It treats Earth as something from which you extract. It creates the sole extracting model of economy. And that is fundamentally the root cause behind all of this. There is no way you can take away the colonial history from it. It is completely tied to it.

Earth has never been under anyone’s control. It is its own thing

Amitav Ghosh

Do you think the billionaires’ race to space and the talk of making Mars habitable is a reflection and extension of that same colonialist mindset?

Of course, it is. What was colonialism but that? Not so much here but in the Americas. They came, as Gandhiji said, like locusts. And extracted. And now that they feel they have extracted almost everything that could be extracted, they want to leave and go to Mars. But just imagine the mindset behind that. Because, what they are actually saying is that billions of people are going to die if you stay here. So, it is better to go. So, essentially, what they are suggesting is a genocidal logic. Let those people die but we can take off. And, actually, you know, the right wing discourse on these things is completely, not explicitly, but implicitly genocidal. Because, what they are really saying is don’t worry, there will be a Malthusian correction, by which they mean billions will die and then everything will be all right. We will go back to living the way we used to.

Jungle Nama and The Living Mountain depict a balanced relationship between humans and non-humans. Like Dokkhin Rai and Bon Bibi. There is a custom of crocodile worship in Goa, Gujarat and in Bengal’s South 24-Parganas. Do you think that focusing on this relationship could help us restore the balance and avert a climate disaster?

Look, at this point a certain degree of disaster is inevitable. Even if we did everything possible, a certain quantum of greenhouse gases are locked into the atmosphere. A certain level of catastrophe cannot be avoided. For me to say that reviving these stories will help us fight the disaster would be presumptuous in the extreme. But at the same time I am not doing it for that reason. I think what is important is to remember that there are other ways of thinking of the world. That there are other ways of conceiving this relationship. The story of Bon Bibi is exactly that. It’s not a simple stable relationship. It’s a relationship that is extremely tense. So it is always spilling over, whether the tiger is killing humans or the humans are destroying tiger habitat. That is why you have a figure like Bon Bibi to create a balance. It’s the same with the story of Manasamangal Kabya. Because she recognises the danger of spillage on both sides, how human greed can take over and destroy the lives of other beings. And how other beings can destroy humans.

So, again, it’s a question of balance. We must never imagine that these relationships are simple. I think that is really one of the primary forces of colonial logic. They imagined that they had controlled nature. Earth was controlled. But it’s not. What we see now is that Earth has never been under anyone’s control. It is its own thing.

Think of the analogy of an elephant that’s sitting down and you are a human being with a big stick. You can go and poke the elephant and then, if you run fast, you can get away for a little while because the elephant takes a long time to get up. But once it gets up, it's going to come after you. And elephants don’t forget. It will catch up with you. And that will be that. That’s exactly what we are seeing now. We poked this being whose intentions, processes of reasoning we do not understand. Now, suddenly, we are discovering that it is acting. It is taking action.

Anyone who imagines that Earth is a sleepy and well-intentioned thing is terribly mistaken

Amitav Ghosh

You are referring to Earth as a living being with intentions. Do you think we have forced Earth to activate its immune system?

Yes, with its own inscrutable intentions. And that’s how we have always thought about Earth. We have spun everything so out of the accustomed parameters that it is hard to see how it can ever settle back to the normality we once knew. It’s interesting to see that in every culture, Earth is imagined as a being, (but) never as a benign being. The Gaia of the Greeks is a very vengeful goddess. She destroys her own husband. She destroys everything that comes in her path. She is always described as the monstrous Gaia. Anyone who imagines that Earth is a sleepy and well-intentioned thing is terribly mistaken. The reality is that the danger is not to Earth. The danger is to us, to humans. Earth will survive. It has been through much worse. It’s really us who will suffer unimaginable pain.

Amit Datta/ My Kolkata

Do you think that the scientific revolution in the West has harmed humanity more than it has benefited it? Has science ultimately become a tool in the hands of the capitalist?

The very roots of science lie in the colonial endeavour. Because the first scientists, let’s say the botanists and geologists, went with the empire builders, basically to establish a dominion, to look for resources. Those efforts are actually inseparable. But I think science itself has also changed. All the sciences are not the same. Climate scientists are extremely concerned about these issues. They are extremely concerned about decolonising science. So these are very important movements. When I think about my college years, there was a very important people’s science movement in India. I think it was quite a pioneering movement. So, I think, we should not paint with too broad a brush…. At this time we need climate science to tell what exactly is happening. But I think technology is much more of a problem, not science as a mode of knowing. It’s the technologists who create all these illusions often.

Amit Datta/ My Kolkata

When will we read you next? Have you started working on your next book?

My next book is a non-fiction. I am pretty close to the end. I think, maybe, another two or three months. It’s historical. It’s really about the ways modern India has been completely shaped by opium; the 19th-century opium industry. Speaking of beings, there is actually no more powerful a being than the humble poppy.