Writing started as a reflective activity for Abdulrazak Gurnah, and was not something for others to see. But it’s this solitary activity and particularly the record of displacement, longingness and hope when he was alone and poor in a new country as a refugee that became the bedrock of his first novel Memory of Departure, published in 1987. And it is this book that made way for 10 other novels that followed, including a number of short stories and subsequently the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2021 “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents” as summed up by the Swedish Academy.

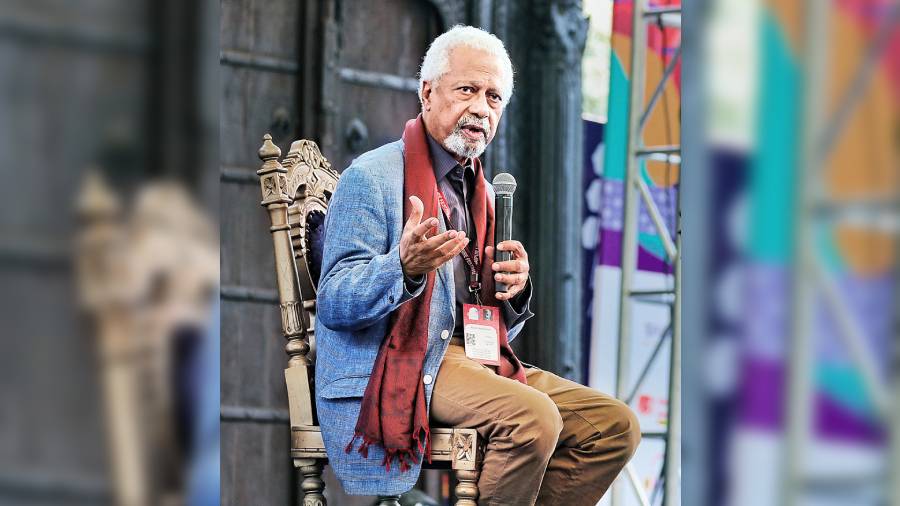

Tanzanian-born Gurnah grew up on the island of Zanzibar and arrived in England when he was 18 as a refugee at the end of the 1960s. He began writing as a 21-year-old in English exile with the theme of the refugee’s disruption running strong throughout his work. And even though Swahili was his first language, English became his primary literary tool aiding in spreading his stories to a bigger diaspora. t2oS met Gurnah, on a sunny afternoon at the Jaipur Literature Festival held last month and the 74-year-old author and emeritus professor of English and postcolonial literature at the University of Kent, appeared relaxed in a blue blazer, post his session at the festival. He spoke at length about life post the Nobel Prize, why the anti-migrant rhetoric in the UK is monstrous now and more.

Awards are not new to you. Your Paradise and By the Sea have been shortlisted and longlisted for Booker Prize while Desertion was shortlisted for the 2006 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. Again, you won the RFI Témoin du Monde (Witness of the World) award in France for By the Sea, among many others. What do they mean to you?

Well, several things. The first thing, of course, is its recognition for your work. And I now find myself included in a team of many writers whose works I’ve been admiring. The other thing is the understanding that an award is a global event. I remember this myself when I was at school. I think we were studying The Old Man and The Sea, the Ernest Hemingway novel that said at the back that he has been awarded a Nobel Prize. So, you knew what that meant, but didn’t know exactly what it meant at that time. So there’s that dimension of it that it’s a global thing, everybody knows about it and therefore that means that the books now become available, they are reprinted, people want to read about your work, and new editions come out.

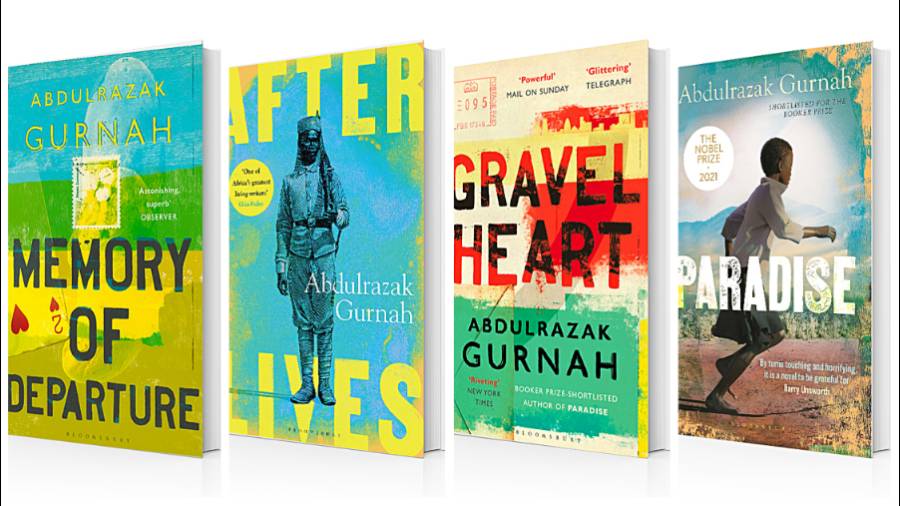

Some of the most celebrated works of Abdulrazak Gurnah

And do these recognitions, particularly the Nobel Prize, create pressure while you are writing your next book?

I don’t know yet because most of the time since then I’ve been doing this (giving interviews) and writing emails.

How has your life changed after the Nobel? And also, how do you keep yourself humble amidst so much attention and publicity?

It’s not hard, really. I have people I know around me who kind of always reassure you because they tell you how stupid you look or how badly dressed you are, or whatever it might be. But it’s not very difficult as I’m not 25; I’ve lived a fair number of years to know what is sensible and what’s not. What’s changed since the Nobel is that I speak to people a lot more than I used to. With new editions coming out very often, especially if they’re a big publishing country, say Germany, or the United States or Scandinavian countries, they’d like me to go there and attend events and so on. So, I meet a lot of people, which is very nice up to a point because it’s also tiring. But it’s okay. I mean, this is the great benefit that comes with the award.

Moving on, you’ve often spoken of your time in England when you arrived as a youngster, and the kinds of anti-migrant rhetoric you faced that made its way into your writing. So, do you see any parallels in the kind of rhetoric we see around immigration and refugees today?

Yeah, there are similarities. I think it’s crueller now. I think there was a certain self-assurance in the UK. Now, I think the UK is a troubled place, there’s some uncertainty that Brexit demonstrates. I think now there is a different way of speaking about foreigners; foreigners are now the government to some extent. So now the foreigners are different from the ones then. But what’s not different is the kind of panic that this issue seems to create, whoever it is as a target but this panic seems similar. And interestingly, of course, a lot of it is driven by how the press presents it.

And do you think it’s ironic that someone like the UK Prime Minister, who is of Indian descent, is propagating a lot of similar kinds of rhetoric?

It is deeply ironic. When you hear the words of members of the government, particularly those who are responsible for this issue, it’s almost shocking that somebody with that experience behind them can speak like this. Don’t ask me how it comes about. Because I don’t know. I just find it incredible. So the word ironic will do but I might even use a stronger word and that is monstrous.

You mentioned Zanzibar this morning as a confluence of cultures. Have you remained in touch with politics and culture in Zanzibar? And if so, do you feel some of the wounds of the 60s have healed and that there is a culture in Tanzania and wider East Africa to bring in a shared vision of the future?

Yes, but it’s an ongoing thing and there’s progress. I don’t know all of East Africa though I’ve been to most different places, you know, a long time ago. So, I don’t know what’s going on in Uganda, for example, though I do know what’s going on in Zanzibar and Tanzania to some extent, and even Kenya. I think all those places have things to be pleased with though none of them is truly properly civil societies, things are moving. Elections are freer, and more reliable, though not completely because people who are in power don’t want to lose power. There’s a lot that needs to be done in the sector of education, hospitals etc. So all of these things can be better. Possibly there is greater tolerance for the kind that you’re referring to. So I think there is a future.

The issue of migration is an old and continuous one, and every country is dealing with it. Do you think race also plays a role in it?

You’re quite right. There’s nothing new about human movement as it’s been going on all the time. And, of course, in the period of European ascendancy, in the 19th century, and earlier, the huge migrations from Europe to North America to Australia, South Africa, etc, everywhere was seen quite differently. What’s different now is that in the last 50 years or so perhaps the movement of people is happening from formerly colonised places into these prosperous spaces, whether it’s North America or Europe and somehow it seems intolerable. And that’s to do with race as people who are coming now are not Europeans. So, race plays a big part in how we perceive the current crisis, if it is a crisis.

Adding to the question, has the situation of refugees improved or have people or countries become more welcoming or empathetic or sympathetic?

In some places, it has changed as there is an increasing awareness though the response is not uniform. There are a lot of people who are working with refugees and lots of initiatives are being taken. Also, there is an awareness that something is not right about the current policies and that presents a criminalising narrative to be used against refugees and asylum seekers. And some countries have been very good like Germany, the Middle East and Scandinavian countries.

What is your writing process?

Well, under normal circumstances, that is to say before something like this, I would probably be at home and divide the time for writing. I get up in the morning at eight o’clock and sit down and write until maybe about three o’clock or so. That’s the regular routine — just sit there every day and write every day. Unless I have to go shopping, and do chores or tend the garden or look after the children.

What are the things that bring you joy other than writing?

Good food, reading, music, gardening, cooking, you name it. I like cricket too but not like Indians you know.

So any advice for young and budding writers?

I don’t think there is any advice other than the simple suggestion that if you want to be a writer, then you just have to keep writing; you have to trust for as long as you can, in whatever it is that you’re doing. I suppose if you’ve been doing it for 20-30 years, and it’s still not happening, you might have to make a decision. But even then, if you want to stick to it, seek it out. Think of examples of writers who are now very famous and eminent like Kafka, who hardly published anything in his lifetime. Some people wait till the 60s and 70s like Penelope Fitzgerald published her first book when she was 60.