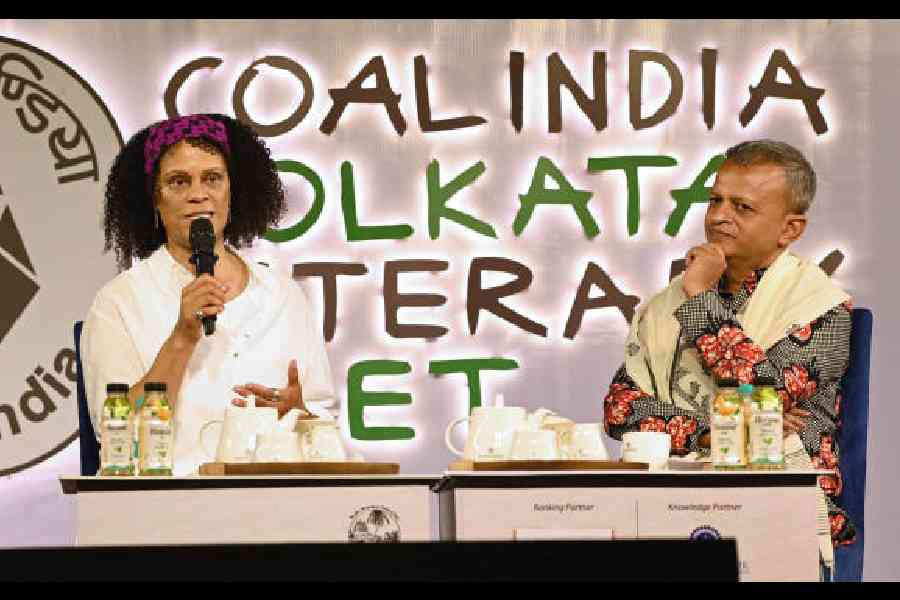

Bernardine Evaristo brought a lot of colour, metaphorically and literally, to Coal India Kolkata Literary Meet in association with The Telegraph, that transcended much beyond her identity as the first Black woman to win the Booker Prize. Her excitement visible in the contours of her face, she also brought energy of a young girl to the literary festival, right from the moment she stepped in the verdant setting of the Horticulture Garden in Alipore, wearing a colourful ensemble rooted to her tradition, and etched her name on the canvas at the inauguration. Calcutta witnessed her elegance, her brand of feminism, her stories from childhood, youth and theatre that shaped her, and more during her sessions — ‘The Evaristo Manifesto’ and ‘Girl, Woman, Other’.

We also saw Evaristo, whose father moved to England from Nigeria 10 years before she was born, talk about her commitment as a writer and literary activist and the need for literature of now to present multiple viewpoints and experiences. “This is a very interesting time in our world. Now more than ever, writers are crucial in exploring the world from multiple perspectives. This is something that I have been committed to as a writer and literary activist for a long time. It is very important that the literature that gets out in the world represents multiple viewpoints, multiple world views, experiences and demographics because at the moment the world is moving towards the point of view that could be potentially damaging for all of us,” Evaristo had said with a sense of urgency in her tone.

In a tete-a-tete with t2oS, Evaristo — whose oeuvre shines with Girl, Woman, Other, Hello Mum, The Emperor’s Babe, Blonde Roots, Mr Loverman and others — spoke about fiction as her happy place, going back to theatre, and why India, particularly Calcutta, deserves multiple visits. Excerpts.

Welcome to Calcutta. How has your first visit to the city been so far?

I really like it, yeah! I’ve been to India three times, but I’ve never been here for very long. And I have realised that I need to come here for a much longer time because it is its own universe; own planet. It’s so different. I’ve travelled to so many places and India is just so different. There are so many layers of activity and engagement. It’s like people saying to me, “Behind those big doors, there’s a mansion.” But opposite the mansion is a slum. And then you’ve got people doing everything on the street, even barbers... literally on the street! That’s not something you see in London very often. In fact, I haven’t seen it anywhere else. So, I just think this is a really deep and rich country and culture, and it deserves me to come back and explore it properly.

In one of your sessions, you spoke about theatre and how it helped you gain experiences and shaped your perspective on feminism and the way you look at certain politics in the world. You also looked at queer politics in another session. How has your perspective as a writer evolved through the years based on what you’ve learned?

Oh gosh! I’ve just changed so much! I mean, I have evolved as a human being over all these years. So, my approach to writing has changed. I have deepened as a person and deepened my understanding of who we are as people, which happens as you go through life, and it has gone into my characters. My understanding of humanity is in my characters and I love that. I love that as human beings, we take in everything that’s going on around us all the time. And, for most of us, there is no outlet for that other than in conversation. But for an artist or a writer, we can put it into a work of art and present it to the world. And maybe that’s what people get when they read Girl, Woman, Other. There are so many different characters. Maybe they see themselves reflected, you know, whoever you are, whatever age you are, whatever sexuality… somehow you’ll be there in the text. That is a really powerful thing to be able to achieve and I’ve only been able to achieve that because of the breadth of my existence on earth and developing my writing skills.

I think everybody is wise. You are wise at 23. You have your wisdom. I have my wisdom. And maybe when you are my age, your wisdom will be a different kind of wisdom. But you still have your intelligence. You have your understanding of people. And that’s what we put into our fictionist writing.

Again, you had mentioned that you don’t want to be boxed when it comes to writing. You worked a lot with theatre and also poetry and verse. Tell us about the transition to fiction. Do you feel like you’re more comfortable in one particular genre?

Honestly, yeah. The funny thing is, I don’t really see myself as a poet anymore. I used to write poems, individual distinct poems, in my twenties. I was writing poetry for theatre. My first book was a poetry book. I think in terms of epic narratives, in one way or another, I can do that through poetry, but I’m not a pure poet, which I used to be. So that’s very interesting for me that I may go back to poetry, but I feel that even though I fused it into my fiction, I’ve also left it behind. So, fiction is my happy place. That’s a terrible thing to say, but it is. I really love fiction. Also, I really love theatre and I’m dipping my toes back in, but I can’t say anything more. But I’m definitely dipping my toes back into theatre.

You mentioned being a pure poet, what would that constitute for you?

Somebody who writes individual poems or they could write like a long narrative poem. They can sit in a coffee shop and they will write a poem. However, I don’t think in terms of individual poems; I think in terms of long stories or even short stories.

Coming back to Girl, Woman, Other, it is remarkable how you weave together the stories of so many different kinds of women. You mentioned Ama being loosely based on you… Did you sketch out the characters in your mind when you started out?

Ama is based on my younger self. I never really sketched the characters out. They form themselves, but it doesn’t come up from nowhere; it comes out of being around people all my life, being around Black women and women of colour all my life. Even though I grew up in a very White area, I had three sisters, you know, so I had three Black women who were my sisters, even though we didn’t think we were Black. And then from the age of 19, I started developing Black female friendships. So those characters came out of my understanding of Black womanhood.

So, when I started to write, Carole, the banker, she was a young woman. And then I start to think, oh, what could she be? I wanted her to be Nigerian, her parents are immigrants. That sounded interesting to me. And then I can’t remember the exact process. At some point, I would’ve thought, she’s going to Oxford because I really wanted to tackle the Oxford thing, I really wanted to get a young Black woman in there. And then it just sort of unfolds, you know, it all unfolds.

Some writers will feel they know the characters inside out before they start writing. They will literally write a biography or something. I don’t do that. It’s much more organic but very rooted in a lot of experience. Somehow the imagination, it kind of runs away with you. The intellect, the magic, all these things are coming into your mind.

Who are the literary figures or influences you look up to?

There are so many books that I love and I’m not very good at reading someone’s entire work. Of course, Toni Morrison is my favourite author. Partly, because I started reading her when I was very young. And I read every book. I jumped on every book. Whereas today, it feels like there are so many great writers and I don’t have the time that I did to read books. So, I’ll read one book by this author and one big book by this author. The books that I’ve read recently includes Marlon James; I think James is a genius. Books like History of Seven Killings and The Book of Night Women are absolutely incredible. I have huge respect for so many authors like Ali Smith and Diana Evans, who’re British authors.